Between Veneration and Destruction: The Venus of St. Matthias

Perspectives from the Comparative Study of Religion

This article discusses the so-called “Venus of St. Matthias,” a former Roman statue of the goddess Venus that has, throughout its history, been embedded in diverse contexts of use. It has been venerated, criticized, rejected, and (almost) destroyed until it found its way into a museum where it is kept to this day. Outlining some of the central stages of this history, the paper intends to illustrate and discuss some of the various types of anti-iconism as outlined in the introduction to this special issue. The object serves as a promising case to elaborate on the possible relations of religion and images and is a good example to explain the heterogenous constellations of iconic and anti-iconic attitudes towards specific objects. The Venus of St. Matthias has been entangled with both iconic and anti-iconic discourse, thus producing a narrative that is inextricably linked with its material substance.

museum, Venus, Trier, material religion, iconism, anti-iconism, iconoclasm, Roman religion, Christianity

Introduction: A Toppled Story

The history of religions around the globe provides ample evidence that all religious groups and traditions, at some point and to varying degrees, discuss their attitude towards images, broadly defined as material and visual means of representation (e.g., Corbey 2003; Besancon [2000] 2009; DeCaroli 2015; Krech 2021, 104–5). While religious traditions are often classified as either hostile or friendly towards images (e.g. Engelbart 1999), it is more appropriate to acknowledge that they usually do not feature a clear, unchangeable position towards images, but that this position is often subject to various factors, such as the social environment of religions or the actual type and motif of the image. The introduction to this special issue (2023) lays out a heuristic typology of iconic, anti-iconic and an-iconic types of religious attitudes towards images, and this article follows the approach outlined there, based on a broad field of publications provided by the material section of religious studies (e.g., McDannell 1995; Bräunlein 2012; Beinhauer-Köhler 2015; Chidester 2018; Kruse 2018). Much of this literature focuses on how proponents of specific religious traditions assess the role and status of images in religious practices. Considering this heterogenous history from the other side, i.e., from the side of the image, it is interesting to notice how one and the same material image may be assessed quite differently from different religious perspectives. Thus, this paper shifts the analytic angle from a focus on a specific religious perspective on images to a specific object and its entanglements with various strands of religious and non-religious traditions and their perceptions of the respective image (here: the statue “Venus of St. Matthias”).

The goal of this paper, therefore, is to contribute to a deeper and more thorough understanding of one specific object, the Venus of St. Matthias, as a case of socio-material entanglement, and to illustrate and discuss the heuristic typology of the relations of religion and images as suggested in the introduction to this special issue. The so-called “Venus of St. Matthias” has been venerated, criticized, rejected, and (almost) destroyed throughout its history, as it was subject to varying religious and non-religious interpretations. It has been entangled with both iconic and anti-iconic discourse, thus producing a narrative that is inextricably linked with its material substance.1

I use the example of the Venus of St. Matthias as a case in point to discuss various aspects of the relationship between religion and images. This object is a particular one because it embodies almost every one of the positions towards images and their material media that we have mentioned in the introduction: Assumedly once venerated as a goddess, it fell victim to rejection and destruction, and was then ‘saved’ in order to be on display and admired by enthusiasts of Roman art in a museum to this day.2

Entangled Histories: Material Objects and Narratives

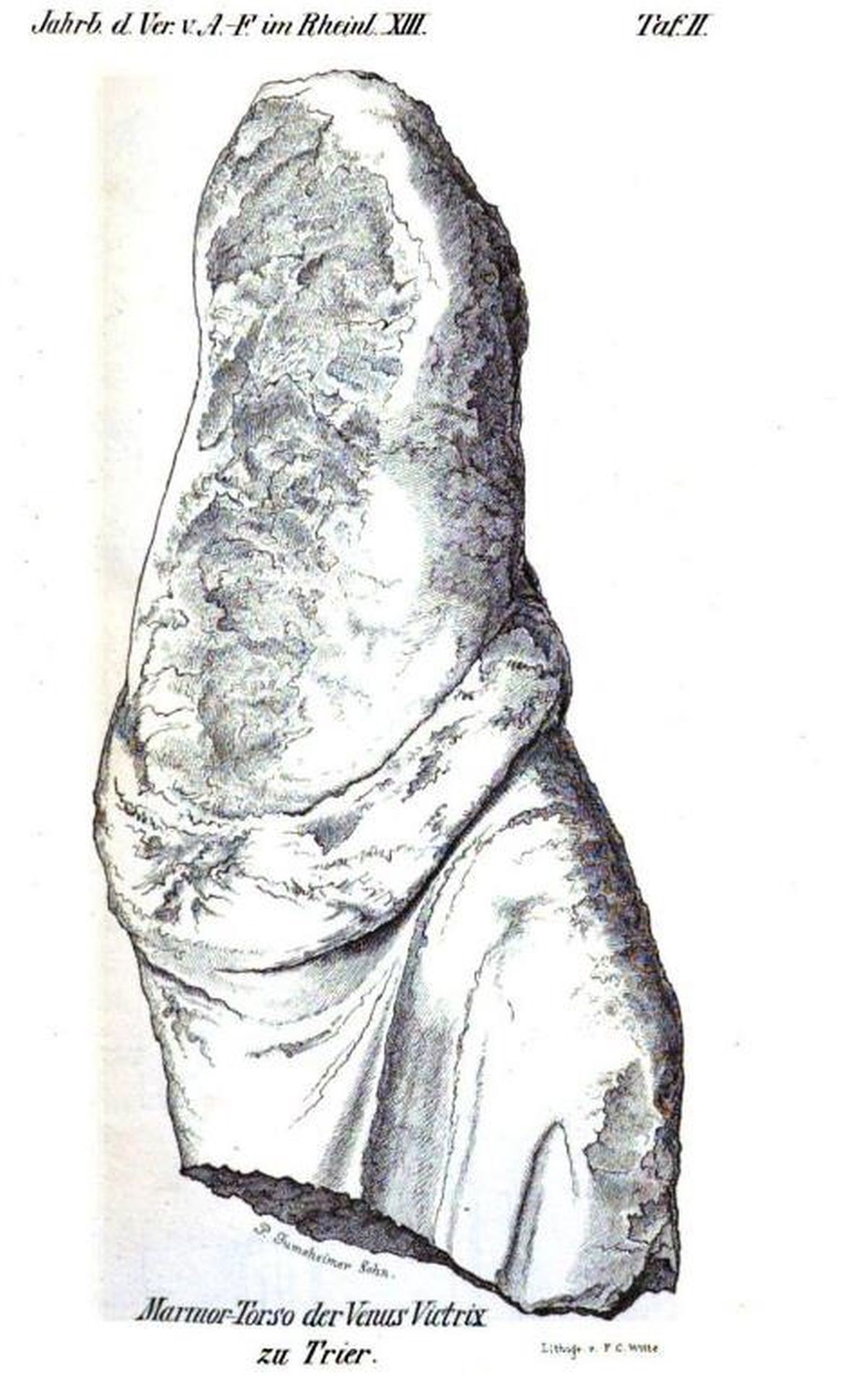

Today, the Venus of St. Matthias (also referred to as “Mattheiser Venus”) is on display in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum in Trier, a city in the southwest of Germany, and one with an important history in Roman times.3 The torso with hardly discernible human features (1) is most often described as the remains of a Roman statue of the goddess Venus. The online museum catalogue explains that this statue was subject to continued stoning by pilgrims who made their pilgrimage to St. Matthias’ Abbey, a few kilometers south of the city (2), which was (and still is) famous for the tomb of Saint Matthias the Apostle. This makes Trier the only city north of the Alps with relics of an apostle, and, besides Rome (St. Peter) and Santiago de Compostela (St. James) one of the three most popular sites of pilgrimage in Europe. As a reason for this continuous iconoclasm, the online catalogue assumes that people wanted to attest to the victory of Christianity over paganism.4 While on display in the museum, the object was often accompanied by two stones lying at the base of the statue, thus exhibiting and keeping in mind this alleged iconoclasm.

When describing the history of this object, I assume that there are two kinds of entangled histories:

- The discourse about the object and its spatial setting: This discourse is available for analysis on the basis of texts, stories, and narratives that have been told and transformed over the centuries (‘history 1’).

- The history of the material object in its spatial setting: This history refers to the actual material object and is rather difficult to reconstruct with historical precision (‘history 2’). While there is no ‘thing as such,’ it is still possible to obtain information about the historical place and state of this object.

Naturally, both these histories are tightly interwoven. They depend on each other and shape each other; they develop as part of the same semiotic arrangement. For analytical reasons, I study them as more or less confined, but mutually co-constitutive entities. In the following, I summarize the historical narratives about the statue (‘history 1’), starting today and moving back in time, while referring to what we know about the actual artifact and its physical-spatial setting (‘history 2’) whenever possible.

This approach (narrating backwards in time) might seem counter-intuitive but is appropriate for two reasons: First, it is an illusion to believe that any story, development, or tradition has a ‘beginning’ that could be pinpointed down to a specific moment in time and unearthed from the depths of history (Krech 2021, 31). The same holds true for the idea of an ‘end’ of something. Therefore, constructing a story from ‘beginning’ to ‘end’ seems overly imposing and does not do justice to the historical evidence (even if this is an important means of ordering and documenting the history of contemporary societies). The second reason is an epistemological one: Chronological developments in time might proceed from moment A to moment B, but constitutionally, we can only understand a situation at a time A by starting with the situation at the time B. The thing that follows after a ‘beginning’ determines what this beginning is (Krech 2021, 32).

Of course, applying this approach as a procedure of analysis comes with considerable challenges, as it runs counter to what we usually expect from a storyline. Still, I seek to present these two histories, reversely told, in a fashion that contributes to a deeper understanding of the Venus of St. Matthias as a socio-material entanglement. What the Venus of St. Matthias ‘really’ is, is not determined by understanding what it was in the ‘very beginning’ but by what later social processes have made of it. In this manner, I can proceed backwards in time, figuring out what people make of the statue, often by pointing to its alleged ‘beginnings.’

On Display to Remember Roman Times

The mentioned entry in the museum catalogue gives a summary of the current knowledge about the object. According to what historians have generally assumed about the statue, it was formerly misjudged as representing the Roman goddess Diana, and, in the middle of the nineteenth century, recognized as a former statue of Venus. In the last couple of decades this has been the widely shared opinion about the artifact both in academic historical publications and in popular literature. Most recently, Alexander Heising, archaeologist and historian of the Roman provinces, mentions the statue in a chapter on the “Reception and History of Research in the Roman Provinces of Germany,” affirming earlier scholarship when he frames the deformed statue as a strategy of “re-using ancient monuments to symbolize the victory of Christianity over paganism” and adopts the assumption that its current condition must be the result of “stoning by devout pilgrims for centuries,” mentioning that it was “hanging on chains in front of St Matthias’ Abbey” (2020, 522).

Philip Kiernan, scholar of Greek, Roman and medieval art and archaeology, confirms that “As late as 1811, it was still traditional for pilgrims visiting the church to hurl stones at the image” and assumes that this tradition began before the sixteenth century. Regarding the motivations of the medieval pilgrims, he suggests that there was not “any fear of contamination from the demon-possessed stone,” nor did the idol “invoke fear and hatred”—instead he speaks of simple “mockery of a long past superstitious practice” (2016, 220–21).

In a popular scientific context, a similar story has been told by Günther E. Thüry, Austrian historian and archaeologist of the Roman provinces, who mentions “church attendees” as the ones throwing stones and understands their actions as a way of proving to each other and to themselves their firm Christian belief. In contrast to Kiernan, however, he assumes that the image had been enchained because Christians feared demonic powers in the pagan statue, “remnants of the old divine power” (2016, 7–8).

In his article about the early Christian history of Trier, Hans A. Pohlsander, expert on late Antiquity in Europe and its architecture, also assumes that pilgrims used to stone the figure to confirm and demonstrate their belief (1997, 278–79n145). In his 2008 book Forgery, Replica, Fiction: Temporalities of German Renaissance Art, Christopher S. Wood, scholar of art and culture of the German late Middle Ages and Renaissance, argues that Roman objects and architectures were generally misinterpreted and misdated in the Middle Ages, and most often fell victim to or were used for new buildings. However, some “spectacular ancient relics remained above ground and on display, held as hostages” (2008, 26). Roman artifacts such as the Venus of St. Matthias, he continues, “carried the charisma [!] of their challenge to Christian iconographical taboos, of their technical mastery, sometimes simply of their size” (2008, 26). He repeats earlier accounts of the statue being publicly displayed “in chains” (2008), while admitting that there is “no telling what the statue really once was” (2008, 26–27), thus referring not to the stories told about it, but to the actual marble torso (history 2). In these accounts the statue is a victim of Christian aggression against pre-Christian Roman religions; and it is kept in a museum today to remember both the Roman presence in Trier, and the Christian ‘ignorance’ in the face of what would today be seen as an example of fine Roman arts. The question if it ‘really’ once was a statue of the Goddess Venus might in fact be irrelevant to the analysis because we have a continuous strong narrative about the statue (history 1), one that is attached to, and in co-constitutive relationship with, the material object (history 2). This narrative, which frames the statue as both the remains of precious Roman art and as a reminder of Christian destruction, is only possible in a social setting that is not dominated by Christian views, such as the contemporary secular art historical and archeological discourse in Germany. However, as the next section will show, this is not just a contemporary discourse but started more than a century earlier.

A Piece of Art and Cultural Heritage Deserving Protection

120 years earlier, in 1877, the Rheinisches Landesmuseum in Trier was founded, taking over many of its objects from an earlier collection (“Museum der Gesellschaft für nützliche Forschungen,” Trier), thus housing the figure in the context of cultural heritage even though this term might not have been used at the time. The Venus of St. Matthias had become an object needing protection, not destruction (as had seemingly been the case before). And after this change of perspective had taken place, it was moved to a secure museum space.

In 1855, Karl Simrock (1802–1876), one of the early scholars of folklore in Germany, published a paper entitled “Pagan Throwing” (Heidenwerfen). He used this expression to refer to the ritual stoning of pagan cult images. He refers to earlier scholarship, such as Florencourt’s analysis (see below), and quotes the Venus of St. Matthias as a prime example of this alleged popular tradition. Comparing this to similar traditions in Germany, he notes that children (not pilgrims or churchgoers) were the ones throwing stones at these images or damaging them in other ways (quoted in Kurtze 2019, 83). His interpretation, and also the term “pagan throwing,” was taken up by later research, as we have seen above, but has recently been proved wrong by Anne Kurtze (2019).

Another decade earlier, in 1847, Wilhelm Chassot von Florencourt had described the torso in an art historical manner (1847, 128). His publication is a turning point in the history of the discourse about the object (‘history 1’), switching from a framing as ‘demonic’ pagan heritage to culturally important Roman art. His writing is considered as the first art historical analysis demonstrating that the torso represents the remains of a figure of Venus (see Fig. 3), similar to the Venus de Milo (on display in the Louvre, Paris; Fig. 1) and the Capuan Venus (National Archaeological Museum, Naples; Fig. 2) (Binsfeld 1982, 47).

His writing about the figure is full of metaphorical descriptions of the “sufferings” of the object. Recollecting the events of 1811, when the torso was moved to the collection of the “Gesellschaft für nützliche Forschungen,” he notes: “Indeed, after such a long punishment and ridicule, the tormented idol was to be granted a final resting place!” (Florencourt 1847, 129).5 He also reports that the statue had once been located right next to the church of St. Matthias where it had been violated by pilgrims. After that, it had supposedly been hanged in chains in the church yard and later buried in a pit, still subject to stone-throwing pilgrims, until it was almost completely buried under stones (1847, 129). Florencourt does not give precise dates for these actions, and it is uncertain how accurate his description is, but it is undoubtful that he addresses the figure from an art historical perspective, pitying its destiny and pleading for its preservation. When he arrives at describing the statue, his words are almost as if he would describe a mutilated human body: “With some traces of a great sculpture, the object presents a picture of violent devastation. The arms, shoulders and breasts have been cut off, and further splinters of the upper body have been severed, so that it appears as a stump that has been narrowed upwards” (1847, 132–33).6 A bit later, he compares the torso with a “corpse mutilated in the melee” (1847, 139).7 His analysis of the object is still cited today as identifying the torso as one of Venus, and not of Diana, which seems to have been an alternative interpretation for some centuries (1847, 140).

According to Florencourt, the last of the French prefects in Trier had pulled the figure out of a hole in the ground, where it had been buried under stones, in 1811, and had workers transfer it to the collection of the “Gesellschaft für nützliche Forschungen” (Florencourt 1847, 129; see also Binsfeld 1982, 43). The president of this society, Johann Baptist Hetzrodt (1751–1830), reports about this event in 1817. This is the first source that mentions the alleged stoning of the statue by pilgrims and the fact that it was kept in a well and buried under stones thrown by devout pilgrims. He still identifies the statue as one of Diana (quoted in Kurtze 2019, 83). Pulling it out of this pit and moving it into the museum of the “Gesellschaft für nützliche Forschungen” was the starting point of the object’s history as a museum object (Kurtze 2019, 82).

It is interesting to note that the French, secular rulers in Trier at the time, were the ones pulling the statue out of its pit and moving it to a more secure environment. Free from Christian prejudice about the statue, they may have understood this as an act of preserving cultural and art historical heritage and as a demonstration of ‘German barbarism’ against the remnants of Roman Antiquity.

Possessed by ‘Demons’ or Precious Art?

In 1802, more than forty years prior to Florencourt ’s seminal analysis, the figure appears on a map of Trier, identified as “Goddess Venus” (Zahn 1979, 308) and located in the churchyard of St. Matthias, close to the Northern wall (Fig. 1) (Binsfeld 1982, 47, 2006, 297).

In 1785, one of the members of said society by the name of Sanderad Müller (1748–1819) had already criticized the iconoclastic actions against this figure. In a lecture, he complained about the destructions and attacks against the statue and pointed out that even for this figure of Venus, people should remember Jesus’ word (John 8:6–8, NIV): “Let any one of you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her” (quoted in Kurtze 2019, 82).

Florencourt quoted older sources, such as a treaty by abbot Johann Bertels (1606), according to which the figure is a “damaged, female torso,” identified in local tradition as the remains of a figure of the goddess Diana, who was believed to be venerated by people living in the area before they converted to Christian faith. Local tradition would also assume that Saint Eucharius, the legendary founder of Trier, had toppled the figure upon his arrival in Trier (Kurtze 2019, 79). The Jesuit Christoph Brouwer (1559–1617) describes the statue as a testimony of Eucharius’ successful mission in Trier and mentions that children would casually throw stones at it and, thus, would have destroyed it to a large extent (Kurtze 2019, 79).

In these centuries, the figure is addressed either as a potentially demonic relic of pre-Christian tradition or as a piece of Roman art. The discourse, in this way, reflects the semantic potential of the figure to be embedded in quite opposite narratives. From the fourth century onwards, it is very likely that the statue was considered as a testimony of the Roman religion and its decline after the ‘victory’ of Christianity.

A Holy Figure of Roman Religion

Following Wood, we may assume that the figure was made in the third century (2008, 26–27), with some likelihood in the context of Roman religion. Klöckner assumes that the statue was carved during the Roman Empire (i.e., in the first three centuries AD) and is based on a type of Aphrodite statue called Capua (this was assumed by earlier research, too) (2012, 29). In Roman times, as Philip Kiernan notes, “Sculpted images played a major role in the construction of public space […].” They

adorned public buildings and spaces both in the centers of cities as well as on funerary monuments on their outskirts. Religious sites could incorporate both statues that were true ‘idols’—that is, objects that were the focus of religious activity and which temples were built to house—and subsidiary decorative sculpture and votive offerings. (Kiernan 2016, 197)

It is impossible to determine which of these functions was held by the Venus of St. Matthias, but we may assume that, in the broadest sense, it was part of Roman religious activity north of the Alps. Kiernan adds that most sculptures in Roman Germany were made of sandstone instead of marble, making the Venus of St. Matthias an exceptional piece (which might have added to its potential of becoming part of a narrative to continue for several centuries). The practice of carving and erecting such statues was popular until the middle of the third century, usually “in or around temples” (Kiernan 2016, 198).

When the Roman empire was gradually ‘Christianized,’ many of the material testimonies of Roman religion fell victim to either intentional destruction or natural decay, beginning in the mid-fourth century, often accompanied by hagiographies of Christian bishops (e.g., Severus 2010, 43) or monks who reportedly destroyed ‘Pagan’ cult images (Kiernan 2016, 206–7). As such, the destruction of the image of the ‘other,’ as outlined in the typology of anti-iconic practices in the introduction to this special issue, is an important element of these Christian religious narratives—which does not mean that intentional and effective destruction really occurred as much as it was narrated (on the re-use of Roman religious architecture for Christian purposes, see also Meckseper 2018).

Later, in the Middle Ages, the

few surviving ancient Roman buildings north of the Alps were always misdated and misidentified, their functions forgotten. Every German town, it seems, had a mysterious dilapidated tower or burial ground to which the label ‘heathen’ was attached. Many churches were imagined to have been built on the sites of pagan temples. […] But no city offered as many charismatic [!] piles as Trier, described by German chroniclers and scholars as the oldest city in Europe.8 (Wood 2008, 27–28)

I will attend to the idea of a “charisma” of statues and architecture in a later section of this paper. At this point, it is relevant to note that medieval historians did not seek exact dating but intended to identify the buildings and figures and to say who built them and how they fit into the contemporary worldview. Trier, for instance, was identified as a biblical city by famous annalist Hartmann Schedel in the late fifteenth century (Wood 2008, 27–28).

As Anne Kurtze has recently demonstrated, the first sources about the Venus of St. Matthias stem from the middle of the sixteenth century (while the inscription is documented already around 1500), and a few decades later they mention children as the ones throwing stones at it (Brouwer). There is only one source, first published in 1817, mentioning pilgrims as the aggressors (Hetzrodt), but this narrative nonetheless gained popularity throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and is still quoted in scientific and popular literature, such as the book by Thüry referenced above, thus producing a story that is not historically accurate but socially effective nonetheless and crucially depends on the violated stone figure. Thus, the damaged materiality of the statue is co-creating the narrative that surrounds it. In terms of social hierarchies, the violated statue can be seen as a visible reminder of the historical narrative that the Christian faith has overcome Roman practice (on hierarchy in architecture more generally, see Memar 2009).

In fact, it makes quite a difference whether the aggressors are identified as “children” or as “pilgrims.” Children would probably be conceived as playing irresponsible but harmless pranks on the statue, which are not really sanctioned because of the statue’s heathen provenance. Pilgrims, however, would attack the statue in some sort of ritualized aggression against the (from their perspective) weak remains of a former Roman religion.

The Inscription and Its Story

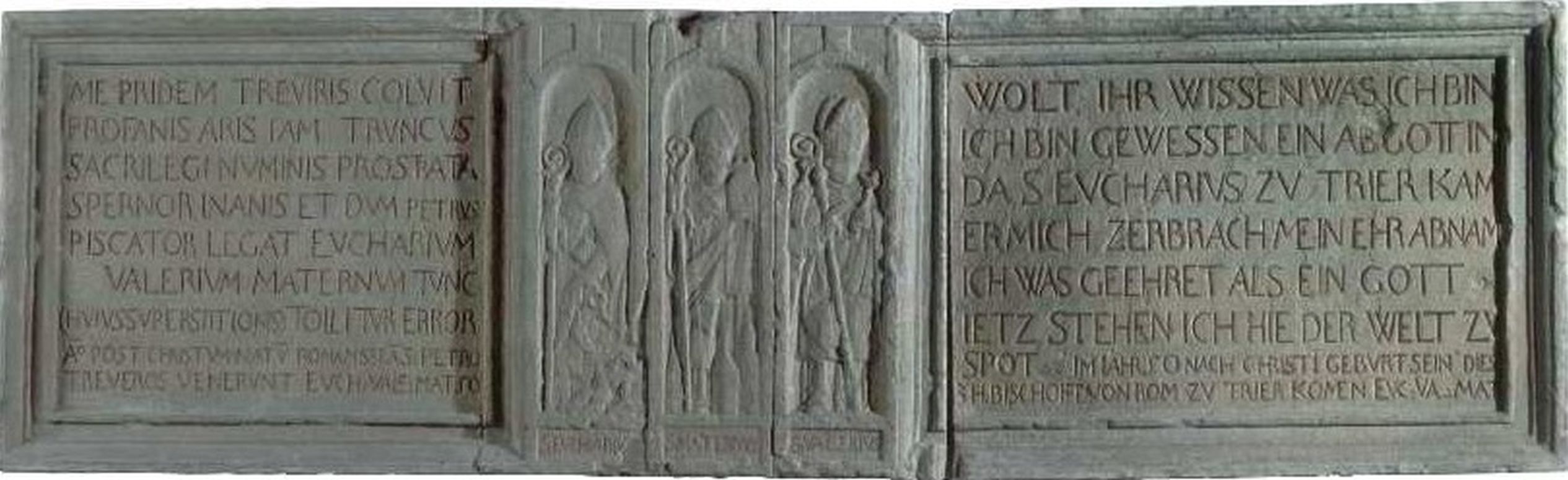

The inscription is an early narrative embedding of the material object, a condensation of the stories with which it was and continued to be entangled. There are two versions of the inscription: The younger one was kept close to the statue in the churchyard until ca. 1890; it is now in the monastery. A copy of it is on display in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum (Kurtze 2019, 80). At some point in the seventeenth century, according to Florencourt, the inscription was renewed (1847, 128) so that there is an older version. This renovation was probably done without much competence in Latin grammar because the text appears almost untranslatable (and is rarely translated verbatim in the secondary literature to date). In 1551, according to Binsfeld, Caspar Brusch (1518–1559) had written about the inscription that it was a “barbarum epigramma, etsi non integrum: perierunt enim aliqui versus” (“a barbaric inscription, and not complete because some verses have gone missing”) (Brusch 1551; quoted in Binsfeld 2006, 298). This source is the first written record about the torso, identified as “Diana” or “Venus” (Binsfeld 1982, 44). According to Florencourt, the inscription had been on the pedestal of the figure when it was still standing next to the abbey, but it was later removed and built into the wall of the churchyard right next to the figure (Florencourt 1847, 128).

The inscription is a foundational moment in the narrative about the statue as it lays the cornerstones of later narrative traditions (Fig. 1). The inscription is not just textual, but also contains a graphic depiction of St. Eucharius, St. Valerius (also known as Valerius of Trèves) and St. Maternus (also known as Maternus of Cologne). Eucharius (left) is holding the end of a chain to which a naked female idol is chained, most likely the figure of Venus (Florencourt 1847, 128)—a pictorial summary of the story narrated in the inscription:9

ME PRIDEM TREVIRIS COLVIT PROFANIS ARIS IAM TRVNCVS SACRILEGI NVMINIS PROSTRATA SPERNOR INANIS ET DVM petrus PISCATOR LEGAT EVCHARIVM VALERIVM MATERNVM TVNC huius superstitionis TOLLITVR ERROR A(nn)O POST CHRISTVM NATV(m) ROMA MISSI A S. PETRO TREVEROS VENERVNT EVCH. VAL. MAT. 50

Binsfeld assumes that this younger version is the incorrect reproduction of an older version and quotes a hypothetical reconstruction of the original version by Caspar Brusch.10 Indeed, Rüdiger Fuchs found severely damaged stone tablets in the Landesmuseum Trier (Fuchs 2006, 1:350) that seem to contain an older (German) version of this text, probably stemming from the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century (see also Binsfeld 2006, 298; Kurtze 2019, 81).

A non-literal translation of the younger Latin version (see above) into English could be:

I was once venerated at the profane altars of the Treveri, my trunk was torn down. I was disdained as ungodly. Once Peter, the fisherman, authorized Eucharius, Valerius, and Maternus, the mistake of this superstition was suspended. In the year 50 A.D., Eucharius, Valerius, and Maternus came to Trier, sent from Rome by Saint Peter.11

These individuals, Eucharius, Valerius, and Maternus, are legendary bishops of Trier. There is no historical evidence about these men; first reports about their relics being transferred to St. Matthias are from the sixteenth century (Pohlsander 1997, 264). It is historically impossible that Trier was founded by contemporary followers of the apostle Peter (1997, 298). However, for the analysis of the statue as part of a socio-material arrangement, it is not relevant whether this legend is historically accurate or not. The narrative exists and it is itself a historical artifact that is unthinkable without the marble torso. This textual evidence refers to the figure in the first person (“I was once venerated …”), thus suggesting that it was perceived to have an agency, a social efficacy (Klöckner 2012, 32).

When studying the semantic embeddings and transformations of this socio-material arrangement, it is therefore important to understand the inscription as one element in a chain of semantic attributions that are intertwined with the material statue. This specific understanding—the figure as a defeated testimony of the ‘Pagan’ past of Trier—proved to be very powerful in the centuries to come, but it was not, as we have seen, the only one. In Roman times, the torso had (in all likelihood, because there is no historical evidence) been addressed in religious communication as a religious artifact, the goddess Venus. Later, it was addressed again in religious communication, but now as part of the non-Christian environment of the Christian social system, the ‘demonic,’ in a manner of speaking; and, eventually, it became part of a semiotic arrangement framing it as an art historical object in need of being saved from religiously motivated vandalism and documenting earlier religious veneration. In a narrow sense, thus, the object can only be described as a “religious object”12 when it is situated in Roman religious practice. Only then is it potentially addressed and venerated as embodying a rightful goddess. When it is part of the non-Christian environment of Christian practice, it is still embedded in religious communication but addressed as the “pagan other,” the religion of the opponent, and, as such, also a document of inter-religious contact. The Christian discourse addressing the figure shows how Christianity dealt with pre-Christian traditions, and how it used the material remains of this past as a means to construct and perpetuate the image of the ‘other.’

As Kurtze has demonstrated, there is no evidence that the statue was indeed stoned by pilgrims over centuries. However, this narrative proved to be so influential that it has been continued and developed in scholarly and non-scholarly literature. In the 1930s, there is scholarly literature quoting the Venus of St. Matthias as the prime example of an alleged tradition called “pagan throwing” (Heidenwerfen) (Kurtze 2019, 84; see above). Even most recent scholarship follows the assumption that pilgrims destroyed the figure to drive out ‘demonic’ forces believed to reside inside the statue (e.g., Klöckner 2012, 30–31). While there has not been any such tradition, according to Kurtze’s research, it is highly relevant that the narrative as such exists, and that it is tied, seemingly inseparably, to the statue.

The Venus of St. Matthias as a Charismatic Object

Elsewhere, I have argued that material objects can be described as “charismatic” in an analytical sense, if and when they are continuously and explicitly “addressed as special or extraordinary” in religious communication and when they are socially effective (Radermacher 2019, 168). This understanding differs from colloquial understandings of “charismatic” people or things which often refer to an inexplicable, pre-linguistic feeling of awe or inspiration.

The notion of “charisma” stems from the Christian tradition and was used in the letters of Paul in the New Testament. Paul believed that every Christian person had a “charisma,” meaning that they were called to serve the community. The notion was used mostly within theological discourse for many centuries until it was taken up by Rudolph Sohm (1841–1917) in the second half of the nineteenth century as part of his historical analysis of the church’s constitution. Famous German sociologist Max Weber took up this idea and used the concept to describe a specific kind of power, i.e. “charismatic authority” (Kehrer 1990) as part of his typology of power (rational, traditional, and charismatic authority). Charisma has traditionally been used to describe a trait of character of human beings. It is a relational phenomenon that needs both the social ascription and confirmation of someone as “charismatic.” In more recent research, the concept has also been used to discuss the features of material objects and architecture. For instance, Ann Taves quotes Weber’s idea of charisma and applies it to material objects that possess “non-ordinary powers that matter to us and that we believe will enable us to do something we otherwise would not be able to do or that would enable something to happen that otherwise would not happen” (2013, 83). Taves defines “charismatic objects” as follows: “Charismatic things are those that afford something (or are believed to afford something) only by means of the thing (person or object) in question” (2013, 93). Based on this definition, I suggest that, material things can be described as religiously charismatic when they are believed to be ‘sacred,’ to possess supernatural powers, and when this belief is expressed in communication. “It is because of these ascribed powers that cultic images and objects are sometimes victims of iconoclasm, i.e., of attempts to disempower them” (Radermacher 2019, 171). The case presented in this current paper draws attention to the flipside of charismatic objects: Their attraction can effect destruction. The charisma of the Venus of St. Matthias is clearly evident in the historical sources, for instance in the writings of Wilhelm Chassot von Florencourt (1847), and this charisma has been explicitly addressed before and after him, to this day, but sometimes in reversed terms. For instance, Thüry writes about the alleged “demonic powers” and the “remnants of an old divine power” in the figure (2016, 7–8).

Some of the Roman relics north of the Alps were regarded as “mirabilia,” which also qualifies them as “charismatic” in this sense. Wood hints at this circumstance, also pointing to their “charisma,” when he writes:

Some few spectacular ancient relics remained above ground and on display, held as hostages. These were the mirabilia, the wonders, a handful of Roman arches and tombs left intact and a small battered corpus of statues. Pagan artifacts carried the charisma [!] of their challenge to Christian iconographical taboos, of their technical mastery, sometimes simply of their size. (Wood 2008, 27–28)

A bit later in his chapter, Wood uses the Venus of St. Matthias as an example, admitting that it is impossible to trace its historical origins (2008, 26–27). It is the narrative in its entanglement with the material statue which makes this object “charismatic.”

Conclusions

The idea of this paper was to present the Venus of St. Matthias as an example for the different kinds of relations between religion and images as outlined in the introduction of this special issue. Obviously, the statue can be employed as an example of both the iconic type, when it was (assumedly) part of Roman religious practice, and of the anti-iconic type (and the iconoclastic action as an extreme variant of the anti-iconic type, see the introduction to this special issue), when it was, according to tradition, rejected and destroyed by Christians in Trier.

Additionally, it has become clear that the discourse about a material object (‘history 1’) does not have to agree with the historical evidence we have about the actual object (‘history 2’). The fact that there is an anti-iconic discursive tradition about this figure is sufficient to draw conclusions as to the attitude of Christian thought towards Roman religion in general, and the Roman goddess Venus in particular.

Kurtze, who has uncovered the series of misquotations and false interpretations in scholarly literature, leading to the narrative of continuous stoning by pilgrims over centuries, suggests that around 1500, when the Venus is first documented in the sources, the monastery of St. Matthias was establishing itself as a center of pilgrimage and, as such, in need of ‘attractions.’ It might have been convenient, Kurtze continues, to conceive a much older tradition around the figure—thus also the inscription which seems to have been made around this time and refers back to the first decades after the initiation of the Christian tradition. In a time when other places north of the Alps (e.g., Aachen and Cologne) were making careers as sites of pilgrimage, it might have been sheer marketing of the abbey in Trier to present the statue and its story in the way they did in the inscription (2019, 85). While this is certainly an explanation of the story, there may be other aspects that deserve consideration, too: For the religious side of the story has to be considered as a historical fact as well, a historical “social fact” in the sense of Emile Durkheim. Social facts “consist of manners of acting, thinking and feeling external to the individual, which are invested with a coercive power by virtue of which they exercise control over him” (Durkheim [1895] 1982, 52). It is the narrative in its entanglement with the material statue which makes this object “charismatic” in the sense described in the previous section. The narrative as such, inseparable (but analytically distinguishable) from the material object, might not be ‘true’ in the sense of historical evidence, but it is ‘true’ insofar as it tells us about Christian attitudes towards images of their opponents.

References

Beinhauer-Köhler, Bärbel. 2015. “Religionen Greifbar Machen? Der Material Turn in Der Religionswissenschaft.” Pastoraltheologie 104 (6): 255–65.

Bertels, Johann. 1606. Deorum Sacrificiorumque Gentilium Descriptio. Köln: Conradum Butgenium.

Besancon, Alain. (2000) 2009. The Forbidden Image: An Intellectual History of Iconoclasm. Translated by Jane Marie Todd. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Binsfeld, Wolfgang. 1982. “175 Jahre Trierer Museen.” Kurtrierisches Jahrbuch 22 (14): 42–47.

———. 2006. “Zur Inschrifttafel Bei Der Venus Von St. Matthias in Trier.” Trierer Zeitschrift 69/70: 297–98.

Bräunlein, Peter J. 2012. “Material Turn.” In Dinge Des Wissens: Die Sammlungen, Museen Und Gärten Der Universität Göttingen, 30–44. Göttingen: Wallstein.

Chidester, David. 2018. Religion: Material Dynamics. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Claussen, Johann Hinrich. 2012. Gottes Häuser: Oder die Kunst, Kirchen zu bauen und zu verstehen. 2nd ed. München: C. H. Beck.

Clemens, Lukas. 2003. Tempore Romanorum Constructa: Zur Nutzung und Wahrnehmung antiker Überreste nördlich der Alpen während des Mittelalters. Monographien zur Geschichte des Mittelalters 50. Stuttgart: Hiersemann.

Corbey, Raymond. 2003. “Destroying the Graven Image: Religious Iconoclasm at the Christian Frontier.” Anthropology Today 19.

DeCaroli, Robert. 2015. Image Problems: The Origin and Development of the Buddha’s Image in Early South Asia. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Durkheim, Emile. (1895) 1982. The Rules of Sociological Method. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Engelbart, Rolf. 1999. “Bild/Ikonoklasmus.” In Metzler-Lexikon Religion, edited by Christoph Auffarth, Jutta Bernard, and Hubert Mohr, 1:155–59. Stuttgart: Metzler.

Florencourt, Wilhelm Chassot von. 1847. “Der gesteinigte Venus-Torso zu St. Matthias bei Trier: Schicksale eines Götterbildes.” Jahrbücher des Vereins von Alterthumsfreunden im Rheinlande 6 (1): 128–40.

Fuchs, Rüdiger. 2006. Die Inschriften der Stadt Trier. Vol. 1. Die deutschen Inschriften 70. Wiesbaden: Ludwig Reichert.

Heising, Alexander. 2020. “Reception and History of Research in the Roman Provinces of Germany.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Roman Germany, edited by Simon James and Stefan Krmnicek, 520–49. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jurczyk, Thomas, Volkard Krech, Martin Radermacher, and Knut-Martin Stünkel. 2023. “Introduction: On the Relations of Religion and Images.” Entangled Religions 14 (5). https://doi.org/10.46586/er.14.2023.10446.

Kehrer, Günter. 1990. “Charisma.” In Handbuch Religionswissenschaftlicher Grundbegriffe, edited by Hubert Cancik, Burkhard Gladigow, Karl-Heinz Kohl, and Matthias Laubscher, 2:195–98. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Kiernan, Philip. 2016. “Germans, Christians, and Rituals of Closure: The Agents of Cult Image Destruction in Roman Germany.” In The Afterlife of Greek and Roman Sculpture: Late Antique Responses and Practices, edited by Troels M. Kristensen and Lea M. Stirling, 197–222. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Klöckner, Anja. 2012. “Von der Anschauung zur Anbetung: Götterbilder im antiken Griechenland.” Gießener Universitätsblätter 45: 29–41.

Krech, Volkhard. 2012. “Religion als Kommunikation.” In Religionswissenschaft, edited by Michael Stausberg, 49–63. Berlin: De Gruyter.

———. 2021. Die Evolution der Religion: Ein soziologischer Grundriss. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Kruse, Christiane. 2018. “Offending Pictures: What Makes Images Powerful.” In Taking Offense: Religion, Art, and Visual Culture in Plural Configurations, edited by Birgit Meyer, Christiane Kruse, and Anne-Marie Korte, 17–58. Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink.

Kurtze, Anne. 2019. “‘Trierer Heidenwerfen’? Die Venus von St. Matthias. Zur Überlieferung seit dem Mittelalter.” Funde und Ausgrabungen im Bezirk Trier 51: 78–87.

McDannell, Colleen. 1995. Material Christianity: Religion and Popular Culture in America. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Meckseper, Cord. 2018. “Zum Architekturverständnis der römisch antiken Bildungswelt.” Göttinger Forum für Altertumswissenschaft 21: 1–27.

Memar, Parya. 2009. Hierarchie in der Baukunst: Architekturtheoretische Betrachtungen in Ost und West. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

Pohlsander, Hans A. 1997. “Die Anfänge des Christentums in der Stadt Trier: Bischöfe und Märtyrer.” Trierer Zeitschrift 60: 255–302.

Radermacher, Martin. 2019. “From ‘Fetish’ to ‘Aura’: The Charisma of Objects?” Journal of Religion in Europe 12 (2): 166–90. https://doi.org/10.1163/18748929-01202004.

Severus, Sulpicius. 2010. Vita Sancti Martini: Das Leben des heiligen Martin. Reclams Universal-Bibliothek 18780. Stuttgart: Reclam.

Taves, Ann. 2013. “Non‐Ordinary Powers: Charisma, Special Affordances and the Study of Religion.” In Mental Culture: Classical Social Theory and the Cognitive Science of Religion, edited by Dimitris Xygalatas and William McCorkle, 80–97. Durham: Acumen.

Thüry, Günther E. 2016. Liebe in den Zeiten der Römer: Archäologie der Liebe in der Römischen Provinz. Oppenheim: Nünnerich-Asmus.

Wood, Christopher S. 2008. Forgery, Replica, Fiction: Temporalities of German Renaissance Art. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Zahn, Eberhard. 1979. “Eine archäologisch-topographische Karte der Stadt Trier aus der Zeit um 1802.” In Festschrift 100 Jahre Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier: Beiträge Zur Archäologie Und Kunst Des Trierer Landes, edited by Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier, 297–311. Mainz: von Zabern.

I would like to thank my colleagues at the Center for Religious Studies (CERES) at Ruhr University Bochum for their support and many helpful discussions as well as for detailed feedback on earlier versions of this paper: Gina Derhard-Lesieur, Licia di Giacinto, Thomas Jurczyk, Volkhard Krech, Dunja Sharbat Dar, and Knut Stünkel. Special thanks to two anonymous reviewers for their incisive and constructive suggestions.↩︎

One aspect which cannot be dealt with extensively in this paper is the question whether there is a particular significance of the figure of Venus to this story. To what extent is it relevant that this figure was identified as Venus and, prior to the nineteenth century, as Diana, two female Roman goddesses often portrayed lightly dressed or half-nude? Were there statues of male Roman gods with a similar destiny? The notion of “female temptation” is a recurring motif in Christian thought, most prominently with Eve being tempted by the snake. Interestingly, Venus also appears in the legend of St. Helena—one of the first female saints of Christianity—who, according to legend, found the cross of Jesus’ death only after divine inspiration telling her to find a statue of Venus (!) in Jerusalem and dig there for the cross. Indeed, the legend continues, Helena found three crosses, one of them identified as the cross of Jesus’ crucifixion, only after a deathly ill woman had touched it and was healed on the spot (Claussen 2012, 41). The relations of Venus in particular and its statues in Christian thought and theology as a case of inter-religious contact translated into the realm of material culture, however, need to be dealt with in future research.↩︎

The settlement had been founded by the Romans who named it “Augusta Treverorum” (“The City of Augustus among the Treveri”). Later, it became the capital of the Roman province of Belgica. When much of the Roman Empire was Christianized, Trier became an influential city for the Christian regions north of the Alps.↩︎

Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier. “G 44d; 1914,1114: Torso einer weiblichen Götterstatue,” last edited May 10, 2023. https://rlp.museum-digital.de/object/5724.↩︎

“In der That war dem geplagten Idol, nach so langwieriger Strafbüssung und Verspottung, ein endliches Ruheplätzchen zu gönnen!” (translation MR).↩︎

“Das Ganze bietet, bei manchen Spuren einer großartigen Plastik, ein Bild gewaltsamer Verwüstungen dar. Die Arme, Schultern und Brüste sind abgeschlagen und daneben noch weitre Splitter des Oberleibes abgetrennt, so dass derselbe als ein nach oben geschmälerter Stumpf erscheint” (translation MR).↩︎

“im Schlachtgewühl verstümmelter Leichnam” (translation MR).↩︎

On the reception of Roman remains in the Middle Ages, see also Clemens (2003).↩︎

German: Wolt ihr wissen was ich bin. // Ich bin gewessen ein Abgottin. // Da S(ankt) Eucharius zu Trier kam, // er mich zerbrach, mein Ehr abnahm. // Ich was geehret als ein Gott.’ // Jetz stehen ich hie der Welt zu Spot. // Im Jahr 50 nach Christi Geburt sein die 3 H. Bischoffe von Rom zu Trier komen. // Euc(harius), Val(erius), Mat(ernus)↩︎

Me pridem Treberis prophanis coluit aris sacrilegi numinis: iam truncus spernor inanis. prostrata spernor, piscator dum legat—error tollitur—Eucharium, Maternum, Valerium tunc↩︎

Many thanks to Gina Derhard-Lesieur for helping with this translation. A German non-literal translation could be: „[Jemand] hat mich einst verehrt an den profanen Altären der Trierer; schon wurde der Rumpf niedergestreckt. Ich wurde als gottlos verschmäht. Und als Petrus, der Fischer, Eucharius, Valerius und Maternus bevollmächtigte, da wurde der Fehler [seines] Irrglaubens aufgehoben. Im Jahr 50 nach Christi Geburt kamen Eucharius, Valerius und Maternus, vom Heiligen Petrus aus Rom geschickt, zu den Trierern“ (a slightly different German translation, based on the older version of the insccription, can be found in Fuchs 2006, 1:656).↩︎

The question of what makes a material object “religious” is immediately tied to the question of a definition of “religion.” This is a discussion that cannot be summarized at length here. It should be sufficient to argue that religion is understood in this article in terms of systems theory as a functionally differentiated subsystem of society that consists of communications. These communications are identifiable as religious if they use the guiding difference immanent/transcendent while dealing with ultimate contingency (Krech 2012, 2021). Relating this approach to material objects, it becomes clear that they are always polysemous, that is, they do not have a fixed meaning, for example, as “religious” or “non-religious,” and that they must always be considered in the context of their immediate communicative context. Accordingly, a material object would be religious in a narrow sense if it is part of a socio-spatial arrangement embedded in communicative processes that deal with the transcendence/immanence difference while dealing with ultimate contingency. In the case of the Venus figure, this is applicable when she is addressed within the framework of Roman worship practices. In the framework of Christian attempts at demarcation, the material object becomes the outside of Christian communication and is then no longer religious in the narrow sense.↩︎