The Archaeology of Cult of Ancient Israel’s Southern Neighbors and the Midianite-Kenite Hypothesis

The Midianite-Kenite hypothesis, the idea that the pre-Israelite roots of Yahwism can be traced back to the areas south and southeast of Palestine, has a long pedigree in biblical scholarship. Analyses supporting this view generally agree in three main points. First, they assume that the influence of the southern cultic practices on Yahwism occurred during a restricted period of time, traditionally dated to the Early Iron Age. Second, they see the origins of Yahwism through the lenses of diffusionist perspectives, characterizing this process as a movement or migration of one or a few determined groups to Canaan. And third, adequate analyses of the archaeological evidence of the arid areas to the south of Palestine are few. In this article I will turn the interpretation of the epigraphic and archaeological evidence upside down. Instead of looking to the (mostly biblical) evidence on the origins of the cult of Yahweh and assuming its genesis lies in movements of people from the southern regions to Canaan in the Early Iron Age, I will focus attention on the history of the cultic practices in the Negev, southern Transjordan, and northern Hejaz during the entire Iron Age, and how this information is related to the religious practices known in Judah and Israel during the biblical period, shedding new light on the prehistory of the cult of Yahweh. I will evaluate the evidence not as a single, exceptional event, but as a long-term process within the several-millennia history of cultic practices and beliefs of the local peoples.

Desert Cults, Archaeology of Religion, Iron Age, Southern Levant, Northwestern Arabia, Yahweh

The Midianite-Kenite Hypothesis

Despite over a hundred years of biblical scholarship, the place where the worship of Yahweh originated is not totally solved. Yahweh did not belong originally to the Levantine pantheon of gods, and attempts to locate the cult of Yahweh in the Semitic epigraphy have proved to be futile (van der Toorn 1999, 910–11; Römer 2015, 35–50). One of the scholarly formulations that stood the test of time is the so-called Midianite-Kenite hypothesis, the idea that the pre-Israelite roots of Yahwism can be traced back to the tribes living in the arid belt to the south and southeast of Palestine—the Negev, southern Transjordan (ancient Edom), and northern Hejaz (ancient Midian). The hypothesis, first formulated in 1862, has a long pedigree in biblical scholarship and until these days remains as one of the most authoritative explanations for the dawn of the cult of Yahweh.1

This idea is primarily based on the interpretation of several biblical passages. A number of biblical texts deal with Moses’ stay in the land of Midian and his relationship with his father-in-law, Jethro the priest of Midian (Exod 2:16–22). It was in the wilderness of Midian that the angel of Yahweh appeared to him in “Horeb, the mountain of God,” and where the divine name was revealed for the first time (Exod 3:1–6). Although Jethro “blessed Yahweh” and offered sacrifices to him (Exod 18:10–12), nothing is said of Jethro as priest of Yahweh and Yahweh as the god of Midian. The matter is further complicated because Jethro is elsewhere identified as Kenite (Judg 1:16; 4:11), another southern group loosely related to the Midianites and Amalekites (Judg 6:3; 1 Sam 15:5–6) that seem to have settled in the northern Negev and was closely related to some Judaean clans (Halpern 1992, 18; Blenkinsopp 2008, 133–6). A second group of texts, some of them poetic and probably archaic, associates Yahweh with locations south or southeast of Palestine. In the Song of Deborah, Yahweh is said to set out from Seir, and to “trod” the land of Edom (Judg 5:4); Seir and Edom appear in this, and in other biblical verses, as regions geographically close, and even as one and the same. The Blessing of Moses repeats similarly that Yahweh came from Sinai, “rose on the horizon” in Seir, shining forth in Mount Paran (Deut 33:2). The prophetic books present analogous imagery, making reference to the southern locations of Teman, Mount Paran, and Bozrah (Hab 3:3; Isa 63:1) (Axelsson 1987, 48–65; Blenkinsopp 2008, 136–9).

The conventional accounts of the Midianite-Kenite origins of the worship of Yahweh, however varied, generally agree in three main points. First, it is normally assumed that the influence of the southern cults on Yahwism occurred during a restricted period of time. Because of its association with the Exodus and/or due to the dating of the archaeological evidence of the early Israelite (or proto-Israelite) settlement in central Canaan, this process is traditionally dated to the Early Iron Age. The oldest extra-biblical source demonstrating the cult of Yahweh as the national god of Israel comes from the ninth-century BCE (the Moabite stele of king Mesha, Tebes 2018), and therefore the ascendancy to pre-eminence of Yahweh cannot be dated later than the tenth century BCE. Thus, the Early Iron Age is generally seen as the temporal framework for the adoption of Yahwism, although some scholars tend to see the ascendance of the cult of Yahweh in the early Monarchy period (e.g., van der Toorn 1996, 282–6). Second, they see the origins of Yahwism through the lenses of diffusionist perspectives—and in some cases they are outright diffusionists, characterizing this process as a movement or migration of one or a few determined groups, whether they be Israelites migrating from Egypt to Canaan or Midianite-Kenite or Amalekite lineages moving from the northern Hejaz to Canaan, carrying with them the belief in Yahweh that was later to be adopted in the central hill country of Palestine. Third, there are not many adequate scholarly analyses of the archaeological evidence of the arid areas to the south of Palestine.

In this article I will turn the interpretation of the epigraphic and archaeological evidence upside down. Instead of looking to the (mostly biblical) evidence of the origins of the cult of Yahweh and assuming its genesis lies in movements of people from the southern regions to Canaan in the Early Iron Age, I will focus my attention on the history of the cultic practices in the southern arid belt during the entire Iron Age as they developed inside the framework of local sociopolitical and economic processes, and how this information is related to the religious practices known in Judah and Israel during the biblical period, casting new light on the prehistory of Yahwism. Contrary to most analyses, I will evaluate the evidence not as a single, exceptional event, but as a long-term process within the several-millennia history of cultic practices and beliefs of the local peoples. Although the extant evidence is difficult to interpret, it is clear that the contact between the Israelite population and the tribal groups in the southern arid belt was a long-duration process with distinct phases, one in which the transfer of religious beliefs and practices was complex and multi-directional.

Cultic Traditions and Processes of Change among the Desert Peoples

One can read a great many accounts on the southern origins of Yahwism without being initiated into the complexities of the local cultic practices and religious beliefs in the Iron Age. Most biblical scholars clearly portray Yahwism as if it arose in a vacuum in the arid southern regions of the Levant, with no previous history and no geographical links with neighboring areas. To the contrary, the Iron Age phenomena are only one link in a chain and a continuation of a long sequence of cultic practices with a history of thousands of years over a large area extending from the Arabian Peninsula to the southern Levant.

The Local Cultic Practices

The semi-pastoral groups moving and settling along the arid belt comprising the Arabian Desert, Negev, southern Transjordan, and Sinai, at least during the four millennia BCE if not afterwards, shared a set of similar cultic or religious practices,2 and indeed a common substratum of material culture. Due to the lack of written sources for the largest part of the history of the desert peoples before the Common Era, most of our information on their religious beliefs comes from archaeological evidence which is difficult to interpret and assess. The understanding of the local material culture is helped by resorting to later literary sources (even from the Islamic Period) and ethnographic sources that should be used with due caution.

Open-air sanctuaries are the most common type of cultic places in the southern desert regions, born from and adapted to the mobile nature of the semi-pastoral peoples. Multiple types of sanctuaries survive and a great deal of overlap between them exists; in addition, iconographic evidence is also present. The most significant components of the material culture that can be related to cultic practices are:

Standing stones (Biblical Hebrew masseboth). Already in the eleventh millennium BCE standing stones were erected in the Negev and Sinai, becoming very popular by the sixth to third millennia BCE, much more than in the rest of the ancient Near East; “in fact, the masseboth discovered to date in these areas outnumber those in all the rest of the Near East combined (this desert area encompasses only one percent of the Near East as a whole, however)” (Avner 2001, 35). Contrasting with contemporary societies in the Levant and Mesopotamia, where the majority of the standing stones were well-dressed, with few exceptions those found in the southern deserts are crude and unhewn. Upright stones appear either as part of open courtyard shrines, incorporated into tombs, or standing alone; in the latter case they stand in a row or in groups of curved, straight, or circular lines, set with their heights symmetrically arranged. Their original purpose has been the object of debate, with some scholars supporting they represent gods and others defending their use for the commemoration of events and persons, the witnessing of treaties, or the demarcation of borders and tombs (Avner 1984, 115–9, 2002, 65–92; Hess 2007, 198–202; Tebes 2020, 502). In fact, the function of each standing stone may have depended on the precise location where it stood, and the preponderance of unhewn standing stones in cultic sites in the southern deserts may tip the scales in favor of the abstract representation of deities, at least for those not found in mortuary contexts.

In previous approaches, this was related to the aniconic nature of the cult of the local peoples (de facto aniconism), sharing this feature with the religions of the Nabataeans and pre-Islamic Arabia (Mettinger 1995, 57–79, 168–74). Whether the groups living in these arid places were completely aniconic or not needs to be nuanced (see Lewis 1998). Although they may well have carried representations of clan or household gods and ancestors as they travelled around, the archaeological evidence for this (for example, statuettes or figurines) is few and sporadic.

Open courtyard shrines. (For the following, see Avner 1984, 115–31, 2002, 92–121; Hess 2007, 200). They are basically spaces delimited by a line or low wall of stones, located along trade routes or near dwelling sites. Their plans vary widely in shape, but a basic typological categorization includes rectangular, quadrangular, circular, and semi-circular designs, while in some cases smaller structures abutted to the main courtyard. Finds consist mostly of local stones—adapted as auxiliary furniture, and used as standing stones, offering tables or benches, altars, and libation bowls—, animal bones, burnt material, remains of metallurgical activities, pottery, and other sorts of small items.

Cairns. They are piles of stones built in layers, covering burial cists or niches (tumuli), marking ritual installations, or commemorating visitations. Their preferred location is standing on hilltops over viewing ancient roads (forming crenelations), although they can also be located inside or around dwelling sites. Most cairns in the Negev and Sinai belong to the Early Bronze Age, although a large number were re-visited and re-used in later periods (Haiman 1992, 25–45; Tebes 2020, 502; for cairns in western Arabia, see Magee 2014, 149).

High-places. They constitute primitive installations on natural hilltops, often equipped with platforms, altars, standing stones and cairns. They appear as early as the Early Bronze Age (Haiman 1992, 38–41), if not before.3

Rock-shelter spaces. They are located next to, or in the crevices of, rock cliffs, containing stone paraphernalia. Although they are not statistically significant, they often house inscriptions of note on the rock surfaces.

Rock art. Due to the perishable nature of most of the archaeological record, it is highly likely that the cultic imagery of the desert peoples was represented in now extinct materials such as wood, leather, and cloth. However, most of the extant evidence comes from painted and incised inscriptions on rocks. Rock art is plentiful from Arabia to northern Africa, appearing in a wide spectrum of contexts, from large rock formations to pebbles in open desert areas, from sanctuaries to mortuary sites. Although there are common motifs that repeated throughout millennia, the chronology and meaning of each one is object of fierce controversy. Among the most common motifs one should mention the scenes of hunting with armed men, the ‘adorant’-type human figures and the depictions of local fauna (ibexes, caprines, ostriches, dogs, camels, horses) and flora (particularly palm trees).4 As we will see below, some of these iconographic elements, particularly the images of men in position of ‘adoration,’ can be interpreted as reflecting cultic beliefs. The distribution of this iconography, however, is not uniform, and there appears to be regional preferences, given different social and cultural backgrounds. Recent statistical studies of the petroglyphs of the Negev demonstrate that during the Early Bronze and Iron Ages the ibex was the most popular motive among the local desert population living in the central Negev Highlands, markedly contrasting with the preference for bulls and other horned animals in the imagery of the towns in the northern Negev (Eisenberg-Degen and Rosen 2013, 245–6; Eisenberg-Degen 2012).

Iconography in pottery. Naturalistic iconography with cultic significance is usual in the pottery of Bronze and Iron Age Arabia; other venues for representation, such as rock art, metal objects, and stone containers, often replicate the depictions in pottery. Well known are the representations of snakes, incised and in bas-relief, in pottery and on bronze and copper items, particularly in southeastern Arabia (e.g., Benoist 2007; Benoist, Pillaut, and Skorupka 2012), and the depictions of human figures and ostriches in the Iron Age pottery of the northern Hejaz (Tebes 2014).

Change and Evolution in the Cultic Practices

The culture of the desert peoples during the first millennia BCE and CE did not exist in isolation; rather, it coexisted with the cultural elements coming from neighboring powerful states that had significant sociopolitical, economic, and ideological interests in the arid areas, such as the ancient Egyptian, Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, Roman-Byzantine and Islamic polities. The imported cultural elements evolved and changed at their own pace, following the ups and downs of the outside sociopolitical developments, in particular the fluctuations and alternations of one dominant power by another. Parallelly, the desert substratum extended through time with gradual variations in its cultural heritage, in a longue durée process in which changes, at times triggered by outside factors, always retained core cultural constituents. The relationship between the local and the imported traditions was as complex as was the contact between the authoctonous groups and foreign powers. Literary and archaeological evidence from diverse periods, but peaking in the first millennium CE, suggests that the reciprocal contacts led to incessant two-way flows of beliefs and practices.

Our main source of data comes from the Late Roman/Byzantine and Early Islamic periods, by far the best-known phases of the long history of human settlement in the southern deserts. Literary and material evidence suggests that, while Christianity and Islam swiftly penetrated into these areas, most of their influence was limited to the few local towns, places where the newcomers rapidly built churches and mosques based on Byzantine and Syrian models respectively. The advent of the two faiths had no immediate impact on the existing cultic practices, and the replacement of the old desert religions was not a clear-cut event, but rather a slow, long-term process that could take centuries. This was most clear in the countryside, where the new religions had to content to exist side-by-side with the traditional practices of the desert. Even when locals formally converted to Christianity or Islam, they frequently modified in one way or the other their new faiths’ cultural elements, adapting them to their millennia-old heritage.

Since the fourth century CE, following the conversion of Roman Emperor Constantine and especially with the establishment of Christianity as a state religion with Theodosius I, Christians put special emphasis on the conversion of the nomadic ‘Saracen’ population of the arid regions south of Palestine, considered to be ‘pagan.’ During the Late Roman/Byzantine period (mid-fourth to mid-seventh centuries CE), several churches were built in Negev towns, such as ‘Avdat, Shivta, Rehovot, and Nessana, and many monasteries were established on the desert fringes, with large numbers of monks flocking to live in them (Figueras 1995). Yet the contemporary literary sources make clear that the locals continued following the traditional cultic practices.5 The archaeological evidence shows that Christianity was by and large restricted to the urban centers, with few if any inroads on the desert fringes. Dozens of standing stones dating to the Byzantine and Early Islamic periods have been surveyed in the Negev countryside, such as those found in Har Saggi in the southern Negev Highlands (Avner 1984, 117–8, 2002, 83 n. 22, 91; Avni 2007, 128; Haiman 1995, 32, 35, 37). Open courtyard shrines continued in popularity among the local population, but what is surprising is that they also found their way into Christian and Islamic practices.6 Cairns have also been found in marginal sites in the Negev Highlands and southern Negev, dated to the Roman, Byzantine, and Early Islamic Periods (Haiman 1992, 27, 42, 1995, 44).

Following the military conquest of Palestine by the Islamic Caliphate in the 630s CE, the new ruling elite began a concerted effort of Islamization of the countryside. However, the process of conversion during the Early Islamic period (mid-seventh to eighth centuries CE) was slow and always partially successful, a two-faced process best illustrated by the rapid construction of mosques within the Negev towns’ residential areas and the parallel endurance of the traditional open-air sanctuaries on the desert fringes. To the already noted continued popularity of the standing stones and cairns in the Early Islamic period one should also add the sustained use of open courtyard shrines, now in the form of open courtyard mosques (Avni 1994, 84–91).7

The Archaeology of Religion of the Southern Desert Areas in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages

Most previous scholarship on the Midianite-Kenite hypothesis, in focusing on the formative period of Yahwism, did not take into account that the archaeological evidence of cultic activities on the southern fringes of the Levant during the Late Bronze and Iron Ages, spanning some eight hundred years, is not monolithic. Although there existed a similar substratum of ritual practices over the whole period, considerable changes are discernible in the material culture, transformations that had to do both with internal developments and with the influence of external religions. If our chronological understanding of this period is correct, it is possible to divide it into three main phases: Formative, Early Contact, and Late Contact Periods.

Formative Period: From the Fourteenth to the Eleventh Centuries BCE

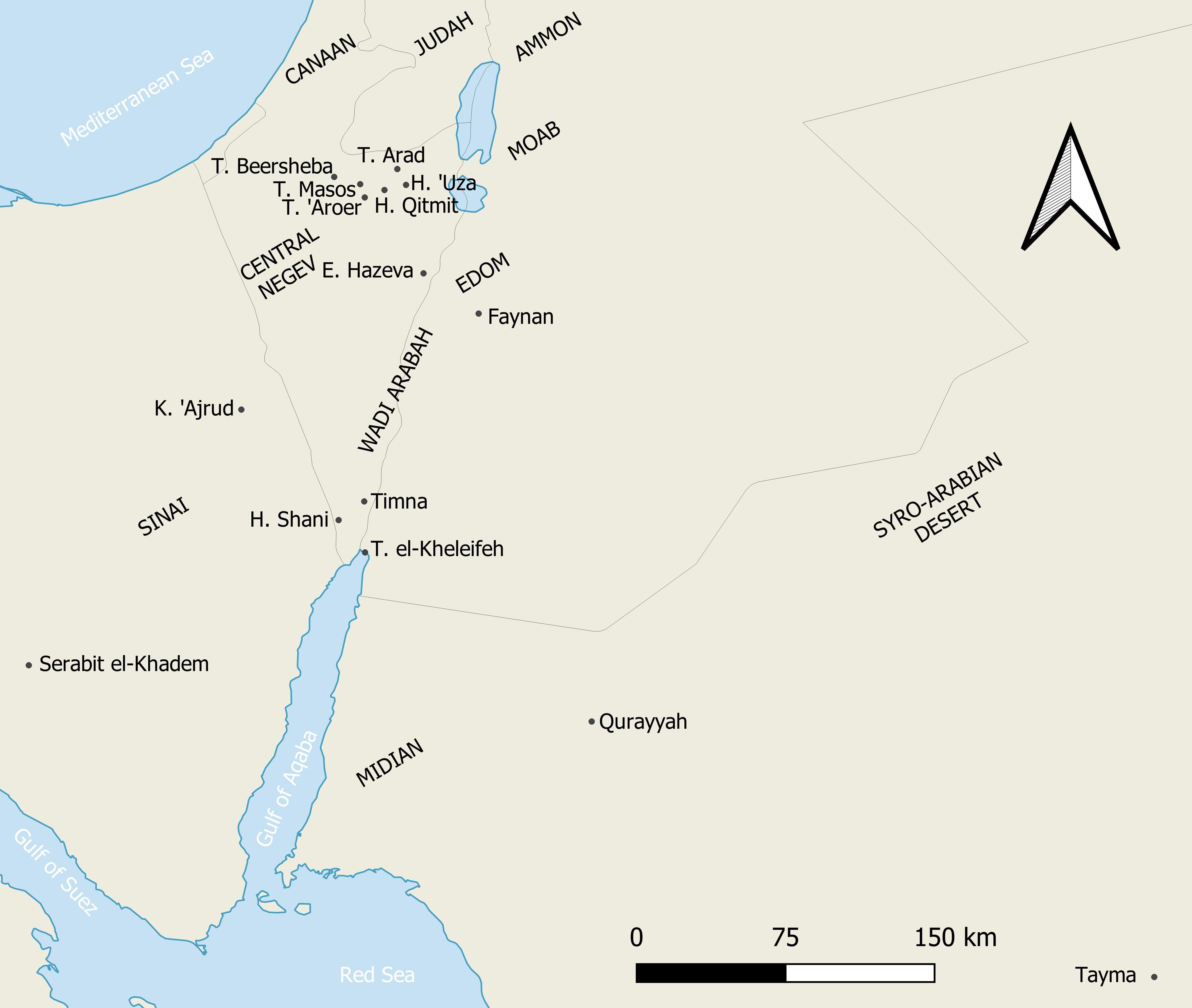

The first evidence of cultic practices in the southern fringes of the Levant that may be associated with the origins of Yahwism appears in the last centuries of the Late Bronze Age and in the Early Iron Age. This period saw the emergence of several sedentary communities located in the northern Negev, the lowlands of Edom, and the oases of the northern Hejaz (figure 1). This development was triggered by the incorporation of the southern Levant and northwestern Arabia into the wider economic world of the eastern Mediterranean since the fourteenth century BCE, through the involvement of the Egyptians in the copper mining and metallurgical industrialization in the southern Wadi Arabah and the growth of interregional trade networks looking for local commodities. Archaeological and epigraphic evidence attests to the existence of a conglomerate of semi-pastoral groups moving through the vast desert tracks of the Sinai, Negev, Edom, and northern Hejaz. Their subsistence, based on the exploitation of pastoral products, prospered through their incorporation into the Egyptian-induced economy, supplying pastoral goods and metals to the Levantine communities and providing workforce to the mining enterprises (Tebes 2013, 39–40). Despite the impression we get from the Egyptian official records, which deal with the local semi-pastoral groups, known as Shasu, as an almost totally military problem, the daily relationships seem to have been largely peaceful. Shasu was the social (not ethnic) term by which the Egyptians knew diverse groups they encountered wherever they engaged in military actions in Canaan; although some Shasu seem to have lived in towns, those present in the Sinai and the Negev are portrayed as having a semi-pastoral way of life (Giveon 1971, 255–8; Ward 1972).8

The combined textual and archaeological data shows that the late second millennium BCE desert communities possessed a millennia-old religious world rich in cultic imagery and practices, while at the same time they had to cope with the influence of the religions coming from neighboring lands, particularly Egypt and Canaan. Far from rejecting altogether the imported cults, the local societies incorporated the new cultural elements to their own heritage, accommodating and reformulating them according to their own social and mental needs. Only a few hints of their ideological realm can be known, yet the available data suggests the early development of the worship of two tribal deities whose greater expansion would occur centuries later: Yahweh and Qos.

The earliest epigraphic evidence that with high probabilities refers to the name Yahweh, if not the existence of his cult, are two New Kingdom topographical lists depicting Shasu people living in the arid lands to the east of the Sinai Peninsula. The inscriptions date to the reigns of Amenophis III (approx. 1380 BCE) and Ramses II (approx. 1270/1250 BCE) and appear in the temples of Soleb and Amara West, respectively. They list several Shasu-lands (tᵓ šsw), most importantly tᵓ šsw yhw (Yahu); the Amara West text also lists a tᵓ šsw s‘rr (Seir).9 As we have already seen, Yahweh and Seir are linked together by a few biblical allusions, admittedly of a very different nature. There is a lot of discussion concerning the location of the “Shasu land of Yahu”: the majority of scholars locate it in that indeterminate portion of land comprising the Sinai, Negev, and Edom, but a more precise setting cannot be established.10 It is impossible to know, with the available evidence, whether the name Yahu refers to a geographical, tribal, or deity name: it could even refer to the three things at the same time, as comparative evidence from other ancient Near Eastern sources may indicate (e.g., the name Ashur, Blenkinsopp 2008, 140). If Yahu was originally the region where the Shasu lived, then its transition to a deity name was extremely atypical for the Shasu-related names: as far as we know, Seir never became the name of a deity. There exists, however, a second name in the Egyptian sources that could have experienced a comparable transformation: Qos.

Similar topographical lists from the reigns of Ramses II (Temple of Amun at Karnak) and Ramses III (Temple of Medinet Habu, approx. 1170 BCE) refer to names with the probable theophoric name Qos.11 Since Qos was going to become the ‘national’ deity or at least the deity favored by the Edomite monarchy during the Late Iron Age, it is a reasonable conjecture that these names are probably allusions to ‘Edomite’ or proto-‘Edomite’ tribal groups subdued by, or at least in contact with, the Egyptians (Oded 1971, 47–50). It is important to bear in mind that, although all these names have several things in common—they come from New Kingdom royal temple lists depicting ‘defeated’ enemies, they are not related in any sense with the Egyptian references to Yahu or Seir. However, they depict a picture in which different deities (or soon-to-be deities if the original geographical names later became teophoric names) were worshipped by the diverse tribal groups living in the Negev and Edom.

Paralleling their political and economic hegemony, the Egyptians profoundly impacted the religious landscape of the Sinai, Negev, Edom, and northern Hejaz, a process illustrated by the establishment of several Egyptian and Egyptianizing temples and shrines in the area. These structures were intended for the worship of Egyptian deities and built according to plans imported from Egypt; however, they accommodated to the desert traditions, taking architectural elements and cultic paraphernalia from the local cultural heritage. They did not operate in a vacuum but cohabited with smaller open-air sanctuaries established by the local peoples with designs, concepts, and functions that were several millennia old. Far from antagonizing, both sets of cultic places were very often located in the same area—at Timna, even as close as several meters—and attended by the same individuals.

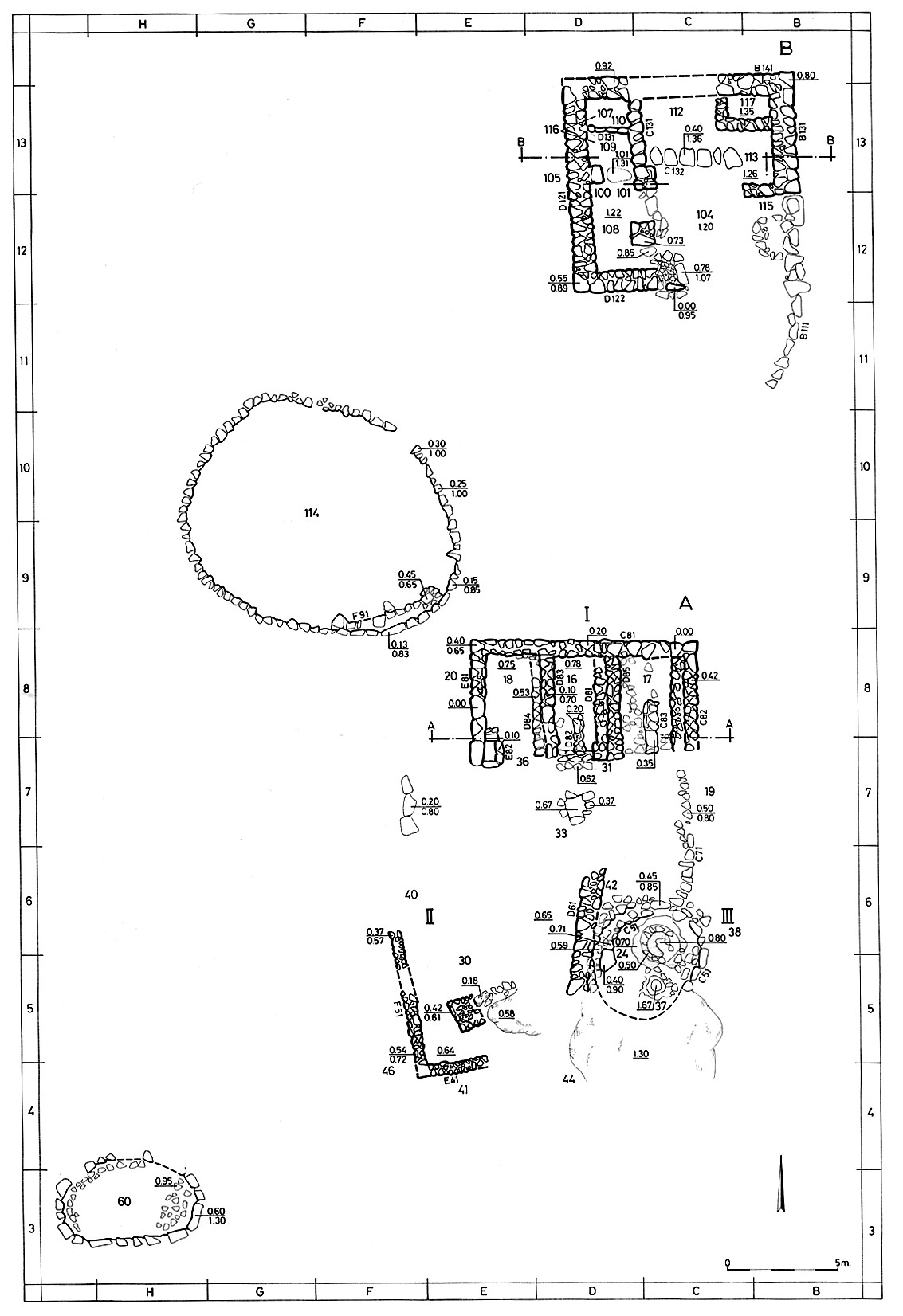

Open-air sanctuaries were found particularly in Timna Valley and adjacent regions; they included open courtyard shrines, high-places, and rock shelters, with associated elements such as worked stones (standing stones, offering benches, altars, and libation bowls), pottery, remains of metallurgical activities, and rock art. At Timna smelting Site 2, three small shrines were excavated: in the valley stood a nearly square courtyard shrine with two semicircular structures attached and evidence of rituals involving fire; it was later abandoned to be superseded by a smaller, rectangular construction built on top (figures 2 and 3). On the flat summit of a nearby hill, a stone structure identified as a high place was found with evidence that small copper votive implements were cast accompanying the rituals. Two smaller, rock high-places were found elsewhere, at Sites 34 and 199, the latter being a shelter space (Rothenberg 1972, 112–19). At Har Shani, 15 km northwest of Eilat, thirteen open shrines were discovered: one of them was excavated to reveal a square courtyard shrine (Sanctuary X) with votive offerings contemporary and similar to those found at Ramesside Timna (Avner 2002, 106–7).

Two or three Egyptian or Egyptianizing temples were established in the southern deserts; although their plan is based on designs typical of temples in Egypt, they depart from them in significant aspects and incorporate local elements in the architecture. Two of these temples, established at Serabit el-Khadem in southwestern Sinai and Timna Valley, areas rich in turquoise and copper minerals, respectively, were dedicated to Hathor, an Egyptian goddess connected with the caves of the netherworld and the mines (Kertesz 1976). As in the open-air sanctuaries, metallurgy was an integral part of the cult. They were defined as ‘rock-shrines,’ that is to say, chapels built into the face of cliffs where a shallow cave or niche was located; a two columned-portico or ‘naos’ and an outer court were placed in the front part (Wimmer 1990). Although they were built for an Egyptian goddess, their design, while following in general terms the orientation of the temples in Egypt, does not fit into the traditional pattern of Egyptian temples (Wilkinson 2000, 238–39): they were basically enlarged rock-cut shrines, here probably acting as a sort of holy-of-holies, with a bent axis, an asymmetry uncommon in Egyptian architecture (Al-Ayedi 2007, 25–26; Avner 2014, 122–3).

The temple at Serabit el-Khadem is the earliest and largest of these structures. It consisted of two cave shrines dedicated to Hathor and Sopdu, each one with an anteroom and an entrance-court, built by the Twelfth Dynasty pharaohs. Several halls emerging from the caves were incorporated in the New Kingdom period, the last one being documented in Ramses VI’s reign (late twelfth century BCE), which in their final design formed a bent elongated structure several meters long. A large number of stelae were scattered around the temple; it is clear from these and other inscriptions that Hathor was considered the patron deity of the miners, identified as “Lady of Turquoise.” Other Egyptian deities, such as Sodpu, Toth and the deified king Snofru, were also worshipped in the temple (Petrie 1906, 72–109; Valbelle and Bonnet 1996, 68–115).

The small temple, or rather shrine, of Hathor at Timna (Site 200) is in fact nothing more than an open courtyard shrine built against the face of rock cliffs (figures 4 and 5). It was probably established by the time of Seti I or Ramses II (early thirteenth century BCE), consisting of an open, squarish court delimited by sandstones and some boulders. A small interior shrine (a ‘naos’) leant onto the cliff with a large niche cut into the cliff rock in its centre, where one figure of Hathor sculpted on sandstone probably stood. The temple was rebuilt under Ramses III (early twelfth century BCE) followed by a third, short layer of occupation in the late twelfth century BCE, when the shrine was reorganized and many of its architectural parts reused for different purposes. No traces of Egyptian occupation survived from this last period, while many of the Egyptian elements were found in secondary use along the south wall, most particularly a row of standing stones incorporating re-used Egyptian incense altars and a square pillar with the face of Hathor on each side (probably mutilated in this phase). According to the excavator of the site, during this phase the temple was used by people of northwestern Arabian origin, the “Midianites” (Rothenberg 1972, 125–79, 1988).

Remains of metallurgical workshops were located inside the second and third layers, suggesting that ritual activities associated with the use of fire took place here. There is no evidence of roofing in the Egyptian phases, and it is assumed that the overhanging cliff rock served as protection. The “Midianite” shrine was probably tent roofed, as evidenced by the folded masses of woolen cloth found inside and outside the walls and two stone-lined postholes in the middle of the courtyard. The several representations of the goddess Hathor discovered inside and around the shrine made it clear that the structure was dedicated to her; one faience object had inscribed her name and the title “Lady of the Turquoise” (Schulman 1988, 143–4). According to recent reassessments of the site’s stratigraphy, the Egyptian ‘naos’ was built next to an already existing local shrine (consisting of standing stones, altar, basins, and drainage channel) which operated before, during, and long after the Egyptian presence (Avner 2014, 116–22; Hess 2007, 202).

Another Egyptianizing cultic structure was recently excavated at Tayma, in the northern Hejaz. It is a small rectangular structure with several broad rooms, tentatively dated to the twelfth-tenth centuries BCE. It was surrounded by a row of pilasters, leaving a substantial open space, identified as a temenos. Although the archaeologists suggest a resemblance with Egyptian or early Greek buildings (Hausleiter 2012, 314–7), the few architectural remains left leave too much room to speculation.

If the epigraphic finds are rather sparse on the deities worshiped in the Formative Period, the iconography in the rock art and pottery provides potentially groundbreaking information on the local cultic practices. At Timna Site 25, a large engraving was cut into the wall in a rock shelter located in a narrow canyon opening into the mountainside. The engraving depicts two scenes of ritual hunting, involving armed men—some being drawn by ox-drawn chariots—chasing ibexes, ostriches, and oryx antelopes (Tebes 2017, 12–19) (figure 6). This was probably a location for rituals, indicated by the remains of large sandstone bowls or basins similar to the ones found in the temple of Hathor. Some 100 metres to the east another similar hunting scene is depicted, this time on the rock wall of a cliff bordering a wadi (Rothenberg 1972, 119–24).

The rock art iconography had an enormous influence on the naturalistic motifs represented in the Qurayyah Painted Ware (QPW), a ceramic type manufactured in the late second millennium BCE northern Hejaz and popular among the villagers and semi-pastoral tribes of the Negev and southern Transjordan. The most salient feature is their bichrome designs carefully painted on small, delicate bowls and containers, which should be the reason why they were considered to have a strong social significance beyond their table-ware function. This can be seen in their deposition as votive gifts to deities (such as in the temple of Hathor in Timna) and as mortuary offerings in tombs, and in their use in administrative contexts (Tebes 2014). Being at the intersection of distinct cultural areas, the QPW iconography exhibits a mixture of Arabian, Levantine, and eastern Mediterranean motifs, particularly evident in the geometric forms and naturalistic motifs.

Naturalistic iconography includes schematic human figures with extended arms bearing external accessories such as headgears or hair, ‘beak’-shaped mouths, hilted swords or daggers hanging from the waist, and false tails; in at least one case, a human figure is holding a palm tree (figure 7). The closest parallels are provided by the rock art of Arabia and northern Africa, where there exist thousands of schematic depictions of men and women, the prevailing position being with the extended arms in position of ‘adoration,’ probably denoting worshippers or sorcerers in ritual scenes. Other common depictions include armed men, possibly representing hunters or tribal ‘chiefs,’ in hunting scenes such as those present at Timna Site 25. The second most common QPW motive are the representations of ostriches, painted following the artistic conventions of the depictions of waterbirds in the Mycenaean and Philistine pottery, above all lateral views of the birds within metopes and detailed representations of their bodies, wings, and claws (figure 8). Depictions of ostriches are, again, very common in Arabian and northern African rock art, probably representing symbols of hunting and power over the animals and nature, and by association emblems of leadership (Tebes 2014). While it is difficult to get its real meaning, the naturalistic iconography is an expression of the religious world of these societies, full of cultic but also social overtones. Here, the otherworld met with men by the performing of intricate rituals mediated through a few important individuals, whose leadership was associated to their performance in war and hunting or through their access to the tribal deities (Tebes 2014, 190–1).

In sum, during the period encompassing the fourteenth to the eleventh centuries BCE we witness in the southern arid margins of the Levant the earliest archaeological and epigraphical evidence of a cultic world that was certainly several centuries old. In the coming centuries, this world, and within it tribal deities such as Yahweh, will begin to be in contact with the neighboring lands to the north.

Early Contact Period: From the Tenth to the Mid-Eighth Centuries BCE

By the late twelfth century BCE the Egyptian hegemony in the Levant had collapsed, leaving a political vacuum ready to be filled by local polities. Local chiefdoms located in the Beersheba Valley and the Faynan lowlands of Edom would soon have to contend with the ascending powers of Israel and Judah. The tenth century BCE witnessed the beginning of a long wave of sedentary settlement in the Negev that was going to extend until the early sixth century BCE, a process initiated by the colonization of the Beersheba and Arad Valleys (and, to a lesser extent, the more arid central Negev Highlands), where newcomers from the northern central highlands founded or re-established towns and fortified settlements overlooking important trade routes such as Tel Masos, Tel Beersheba, and Tel ‘Arad (Tebes 2013, 10–12). The political affiliation of some of these sites is not clear, particularly in their early phases (Tel Masos III-II, Tel Beersheba IX-IV), where strong local elements are evident in the architecture and material culture. But from the late tenth century BCE on, any local polity still existing in the northern Negev was replaced by a network of small Judaean villages and fortified posts.

And from the tenth century BCE on we also have the earliest evidence of solid contacts between the northern populations and the peoples living in the arid southern margins. The religious activities of the northern settlers were concentrated on a few cultic centres built within the northern Negev sites. The earliest evidence comes from Tel Masos II, site probably dated to the tenth century BCE, where several artifacts found within a copper workshop (House 314) suggest a cultic context. These include four anthropomorphic stone figurines similar to the molded stones deposited as votive gifts in the Hathor shrine at Timna and eight Qurayyah ware sherds, probably part of a single vessel (Fritz and Kempinski 1983, 40–41, 87; Tebes 2013, 55, 64–65). Like in the Timna shrine, ritual practices associated with the use of fire probably took place inside the structure.

The best-known shrine is a small tripartite structure excavated in the Judaean fort of Tel ‘Arad X–IX; it stood for some 40 years in the mid-eighth century BCE (see Herzog 2002). The shrine consisted of a front square courtyard and a main-broadroom (hekal) with a protruding chamber (debir) at the back (figure 9). This plan is certainly not local, and most of the parallels that have been adduced come from Syria-Palestine, being tripartite temples or four-room houses. It is commonly identified as a Yahwistic shrine based on an ostracon letter found in the site mentioning the “house of Yahweh” (Aharoni 1981, 35–38), although this could easily refer to the temple of Jerusalem as well. Even if Yahwism was the main focus of worship at ‘Arad, the rituals performed at the shrine seem to have been influenced by the southern practices, illustrated by the finding of one or perhaps two or three standing stones. One was a limestone stele with traces of red pigment found in the cella, where it was originally erected. The other two were smaller stone slabs found plastered into walls; although the finding of two altars blocking access to the cella would support their identification as standing stones, their size and placement suggest they probably were constructional elements of the temple (Bloch-Smith 2015, 101). Whatever their number, the standing stone/s unearthed at ‘Arad served as aniconic representation/s of one or more deities worshipped at the site.

Less conclusive is the evidence from Beersheba III, where several blocks belonging to a tall four-horned altar were uncovered within a fieldstone wall. The altar was probably incorporated within a temple, the remains of which have not been found (Aharoni 1974).12

Kuntillet ‘Ajrud is the site that has attracted most of the attention. It was probably established by the northern kingdom of Israel or by Judaeans as subservient of their northern neighbors, given the mixture of Israelite and Judaean cultural traits (pottery, script) found at the site (Meshel 2012). Established between the late ninth and the mid-eighth centuries BCE on a hill 15 km from the Darb Ghazza, the road connecting the Gulf of Aqaba with Gaza, its function is still debated, as it has been identified as a fort, caravanserai, or cultic center. Whatever the real function of the site, what is significant is that Kuntillet ‘Ajrud was visited by people who carried out highly hybridized cultic practices, leaving inscriptions on pottery, stone bowls, and plaster walls with dedications and blessings in Hebrew to their preferred deities, including Yahweh, but also other Canaanite or Phoenician gods like El, Baal, and probably Asherah. Some of these texts may have even been inscribed in Phoenician script and/or language by either Phoenicians or Israelites. Most famously, inscriptions on two large storage jars mention “Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah” (Pithos A) and “Yahweh of Teman and his Asherah” (Pithos B) (Ahituv, Eshel, and Meshel 2012, Inscr. 3.1, 87–91, 3.6, 95–7, 3.9, 98–101).13 Yahweh is here clearly associated with, if not being a local deity of, the southern site of Teman. Decorated pithoi left by the passing travelers to make their wishes and requests present to the deities (Frevel 2008, 40) probably served as subjects of libation rituals, votive and dedicatory gifts, incense burning, and ritual meals (Schmidt 2016, 15–122). The architectural layout of the main building is very different from contemporary southern Levantine shrines such as the one excavated at Tel ‘Arad, but it does not preclude the presence of one or more deity statues that would have been removed when the site was abandoned, had they been present.

Northern ritual installations coexisted with others that continued the traditions of the desert. Excavations in the central Negev and northeastern Sinai have found cairns in small Iron Age sites, such as Wadi el ‘Asli and Wadi el Huar (Haiman 1992, 27, 42, Fig. 22:5,6), and Early Bronze cairns re-used in the Iron Age, as in the Nahal Mitnan and probably Har Horesha (Saidel and Haiman 2014, 21, Fig. 2.36, 2.37, 34). Since these cairns heavily contrasted with the types of burials popular in Iron Age Judah and in Judaean sites in the Negev, they were probably established by local semi-pastoral groups now sedentarized and not by people migrating from the north (Ilan 2017, 60). The continuation of the ancient traditions of desert mortuary architecture is no more evident than in the arid environment of the lowlands of Faynan, in southern Jordan. Here, a large Iron Age nomadic cemetery with a total of 245 cist graves was excavated in the Wadi Fidan 40 site, and dozens of more graves were left untouched. The graves were accompanied by standing stones, some aniconic (unworked or smoothed) and other anthropomorphic (shaped and smoothed) (figure 10) (Beherec, Najjar, and Levy 2014).

The mixture of northern and southern features is also present in the iconography painted on the storage jars of Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, especially on Pithos B, which depicts five figures standing in one line, identified as worshippers in procession (figure 11). These figures closely resemble the representation of ‘adorant’ figures so popular in the Arabian rock art and the QPW, in particular their schematic rendering, their raised forearms, and the hair coming out of their heads (Beck 1982, 45, 62, 2012, 176–77; Tebes 2014, 175–76). The pictorial absence of deities associated with these figures has been related to the empty space aniconism so common in the religion of the southern arid regions (Schmidt 2016, 22–23, 45, 81, 89–90). The rock art imagery also influenced the painted decorations in post-QPW ceramics of the northern Hejaz. QPW naturalistic motifs, such as birds and palm trees, continued with more abstract forms in a later, regional style known as Taymanite pottery, dated to the tenth to eighth centuries BCE (Tebes 2015).

It is during the Early Contact period that the southern populations had, for the first time, wide-ranging contacts with the newcomers of the northern central highlands, leading to a new era of two-way transfer of cultic traditions and material culture. Thus the adoption of the cult of Yahweh by the northern populations cannot be dated before the tenth century BCE.

Late Contact Period: From the Late Eighth to the Mid-Sixth Centuries BCE

Since the last decades of the eighth century BCE, the Negev and Edom experienced a second, larger wave of sedentary settlement. This development should be attributed to two main factors: the development of trade in south Arabian incense, leading to the founding of trade stations, forts, and towns along the trade routes; and Assyria’s meddling in local political affairs. In the Negev, the Pax Assyriaca assured the vitality of the trade routes, cemented the movements of commodities from east to west—the Wadi Arabah acting as a bridge more than as a barrier, and in some cases probably gave more power to the local tribal groups in detriment of the petty kingdoms formally ruling in the area. Although officially under the authority of small polities such as Judah, the Philistine city-states, and Edom, most of the area was contested lands between these petty powers and the tribal semi-pastoral groups that moved throughout the desert and to a large extent controlled the lucrative Arabian trade (Bienkowski and van der Steen 2001).

This new scenario encouraged the flow of two-way movements across the Arabah, with caravans bringing Arabian goods eager to reach the Mediterranean markets and nomadic groups looking for pastures for their herds on both sides of the Rift. One of the most important archaeological traits of this period is the presence of large quantities of Southern Transjordan-Negev Pottery (STNP, traditionally called ‘Edomite pottery’) in Late Iron Negev sites, which included shallow decorated bowls, Assyrian-influenced carinated bowls, and closed cooking pots. STNP became the most popular ceramic horizon in the Late Iron sites in the Edomite highlands, also being adopted in contemporary Negev sites, where it coexisted with the local tradition of Judaean wares (Tebes 2013, 87–109; Singer-Avitz 2014). What is most interesting is not only the preponderance of locally-made STNP forms in the Negevite assemblages, but also the fact that apparently all of the cooking pots belonging to this group were manufactured with materials collected in southern Transjordan and the northern Arabah (Freud 2014). This data suggests a steady flow of people and goods between Edom and the Negev, following the trade routes and the nomadic itineraries. In this process, some families and clans of southern Transjordanian stock began settling in the Negev sites, especially along the northern valleys, bringing with them their own folklore and cultic traditions.

The rapidity with which an ethnically, heterogeneous community crystallized in the Negev during the Late Iron Age is most obvious in the epigraphic record and the material culture showing the cult of Qos. This deity is generally associated with the Edomites and their monarchy because of its appearance as a theophoric component in the personal names of Edomite kings mentioned by Neo-Assyrian documents. But since the epigraphic evidence of Qos appears conspicuously in northern Negev sites that were under the nominal control of Judah, worship by Judaeans is not only possible but likely. There is a reference to Qos in an ostracon found at Horvat ‘Uza, while personal names with the god’s name were found at Tel ‘Arad, Tel ‘Aroer, Horvat Qitmit, and Tell el-Kheleifeh (Knauf 1999). Although some scholars have suggested an Arabian origin of the worship of Qos, there is no epigraphic evidence of his cult in the northern Hejaz in this period. The scarce data, the majority coming from Tayma, points instead to the worship of Aramaic gods such as Salm, Sangila and Asima, introduced probably as early as the eight century BCE (Maraqten 1996). Two large temples were likely associated with the worship of these deities, although they are of post-Babylonian period date (Hausleiter 2012, 304–14).

The new sociopolitical scenario, characterized by the central role of the local semi-pastoral groups and the more secure trade routes, encouraged the establishment of cultic centers outside settlements, such as the open sanctuaries at Horvat Qitmit and ‘En Hazeva. These structures, while following the local tradition of open courtyard shrines, incorporated architectural elements and cultic paraphernalia imported from the sedentary societies of the southern Levant. The cultic sites at Hazeva and Qitmit were road-shrines built next to major trade roads and used by passing semi-pastoral groups or commercial caravans. Although identified as ‘Edomite’ shrines because of the findings of epigraphic material referring to Qos or with ‘Edomite’ script, their eclectic style indicates that individuals of diverse ethnicity worshipped there (Finkelstein 1995, 149–52).

The cultic site at Hazeva consists of a small open elongated structure, built a few meters outside the walls of the Stratum V fortress; next to its foundations stood a favissa (a cultic pit) with a large number of deliberately smashed cultic vessels, standing stones, and altars. According to the archaeologists’ reconstruction, the standing stones formed a squared U-shaped wall that was open on one side, accompanied by stone benches and altars (figure 12) (Cohen and Yisrael 1995, 25–27; Ben-Arieh 2011), a design very much resembling the standing stone-sites of the desert cult. Similar cultic vessels were found in a high-place located at the nearby hilltop site of Givat Hazeva, with remains of metallurgical activities a few meters away (Tebes 2013, 64, 78).

The shrine at Qitmit was established on a hilltop away of any settlement, and was built following the tradition of the desert open courtyard sanctuaries, with adjoining architectural elements coming from the north. It comprised two complexes, each one with a covered multiple-room structure, and a rectangular open courtyard adjoining to the south. Two elliptic open enclosures with standing stones and benches were found a few meters to the west (figure 13) (Beit-Arieh 1995, 9–26).

The cultic vessels and statuary found at the Hazeva and Qitmit shrines, although identified as ‘Edomite,’ present features general to the religious iconography of the Iron Age Levant. Like the inscribed pithoi found at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, the statues symbolically presented an action before the divinity, envisioned as a request or a supplication (Frevel 2008, 42). The Qitmit assemblage is the richest and most varied, showing bearded anthropomorphic statues holding swords (resembling similar statuary found in Ammon and Moab) and a head with facial features and horns, identified as a deity. Very significant is the diverse animal iconography in the pottery applications and figures, including bulls, ibexes, dogs, cocks, doves, and ostriches (Beck 1995; Ben-Arieh 2011). Based on the statuary and the votive gifts, the two shrines can be identified as sanctuaries of a weather god with martial features, perhaps Qos, identified by warlike (warrior figures, sword-votives) and hunting (ostriches and related animal iconography) attributes. This imagery noticeably differed from the iconography present in the Iron Age rock art of the central Negev Highlands, where the ibex was the most popular motive depicted by the local semi-pastoral population (Eisenberg-Degen 2012).

To sum up, from the late eighth to the mid-sixth centuries BCE, the southern arid regions and the central Levant were highly interrelated. Not only did Judah’s hegemony extend over the northern Negev during this period, but a peak in contacts with the southern Transjordanian Edomites also led to transregional flows of deities and cultic traditions—most particularly Qos.

Southern Elements in the Israelite Cult

Our study indicates that we should not persist with the old paradigm that saw the cult of Yahweh as adopted in a totally formed, closed form in the Early Iron Age from Midianite-Kenite groups. Contrary to what is usually imagined, the embracing of southern cultic practices was a long duration process spanning the entire Iron Age. These events should not be seen as separate from other periods in the history of the lands to the south of Palestine and as disconnected from neighboring arid areas. There are four elements that can be tentatively attributed to the original southern folklore:

Aniconism

We noted the centrality of the aniconic practices in the cult of the southern desert peoples, for whom the cult of standing stones was a legitimate form of worship. The Levantine cult involved the worship of dressed stones, a practice almost totally foreign to the southern desert peoples, where the presence of unhewn stones was the rule. The aniconic nature of the desert deities, such as Yahweh and Qos, would explain their absence in the pictorial record of the Negev and Edom during the Formative Period—such as the rock art of Timna Site 25 and the QPW painted motifs, precisely the time when the Egyptian sources mention the existence of their cult. Evidence of aniconic practices in Yahweh’s cult at ‘Arad and Kuntillet ‘Ajrud suggests the presence of aniconism in the pre-exilic Israelite and Judaean religions.

The question, of course, is if the southern aniconism is related to the biblical image ban (Exod 20:4; Deut 5:8) and to the aniconic worship of Yahweh in pre-exilic times, defended by some scholars (Mettinger 1995; Na’aman 1999; Miller 2000, 16–17). The practice of divine representation in Iron Age Israel and Judah was not monolithic and contained both the figural and non-figural portrayal of deities (Uehlinger 2019, 110). There are several indirect pieces of evidence, including biblical references as well as epigraphic, iconographic, and archaeological data that, taken together, point clearly to material representations of deities in the kingdom of Israel, particularly bovine imagery that would represent Yahweh.14 The southern Yahweh, now incorporated into the northern Israelite pantheon, assimilated divine features of his Canaanite rival Baal, among them his identification with the bull. The question is more complicated for Judah, given that – despite clever interpretations of some biblical references (Römer 2019, 200–202) – there is no clear evidence linking the Yahwistic cult with an anthropomorphic image, in the temple of Jerusalem and elsewhere. The different systems of divine representation present in Israel and Judah could tentatively be attributed to the influence of the southern desert cults on the Judaean cultic practices.

Yahweh as a Hunting/War God

The presence of symbols of hunting, war, and leadership in the cultic iconography of the desert rock art suggests that the local tribal deities were inextricably related to these values. It is important to note that hunting was not a significant subsistence activity for the desert societies of the Negev and Sinai at least since the Early Bronze Age, when the economy based on pastoralism first emerged. The local osteological record demonstrates that since that period bones of domestic sheep and goat are predominant, whereas bones of hunted animals are rare (Horwitz 2005). This, however, vividly contrasts with the preponderance in the Early Bronze/Iron Age petroglyphs of the central Negev Highlands of hunting scenes where the hunted animal is the ibex. Thus, the meaning of this rock art should not be seen as reflecting literally specific historic events, but probably expressed deeper mental metaphors, such as the human control and destruction of the natural animal world (Eisenberg-Degen and Rosen 2013, 245–6; Tebes 2017).

Yahweh’s descriptions as a war-like deity ready to defend his people (e.g., 1 Sam 7:10; Psalm 18:29–45; 89) and his epithet “Yahweh Zebaoth” (Miller 2000, 7–11) are probably echoes of his origins as a tribal deity related to the world of hunting and war, and possibly a cause of his competition with Canaanite god Baal as warrior-gods (Smith 2002, 47, 79). This imagery is related to the representation of Yahweh as a heavenly storm-god, particularly in (admittedly difficult to date) biblical passages pointing to his southern sanctuary (Deut 33:2; Judg 5:4–5; Psalm 68:8; Hab 3:3) (Smith 2002, 80–81).

It is certainly not a coincidence that the most dominant deity in the southern Levantine iconography of Iron Age IIA is the ‘Lord of the Ostriches’ motive, composed of a human figure with upraised hands standing between two ostriches, appearing in scarabs, amulets, and pottery (Keel and Uehlinger 1998, figs. 162a–d, 195a; Pfitzmann 2019). Although now mostly extinct, ostriches were animals native to the Negev and northern Arabia, and therefore the ostrich imagery in the settled southern Levant should be considered an import. We have seen how the iconography of the ostrich present in the Qurayyah pottery reflects to a large extent the themes of hunting and power present in the plentiful rock art of the region.15

Qos, a deity far less known, in all probability had similar characteristics, to judge from its Arabic etymon (qaus, “bow”) and the martial and animal attributes displayed in the statuary and votive gifts found at Qitmit and Hazeva (including, not surprisingly, lots of clay figurines with the form of ostriches), pointing to his identification as smiting god and “lord of the beasts” (Knauf 1999, 675–76).

Pilgrimage

The practice of pilgrimage to sacred sites was central to the religions of pre-Islamic Arabia, phenomenon well known thanks to its persistence in the Muslim Hajj but with good archaeological evidence extending in the past at least to Neolithic times (e.g., pilgrimage and ritual sacrifice in fifth millennium BCE Shi’b Kheshiya, southern Arabia) (McCorriston 2011). Both textual data, coming from the Hebrew Bible and the Hellenistic period, and archaeological evidence point to the pivotal role of pilgrimage in the Israelite religion, likely being part of the southern heritage brought by the adoption of Yahweh’s cult. The city of Jerusalem, as is well known, was and still is the fundamental nexus of the Jewish experience of pilgrimage, but this position was acquired relatively late in the history of the ancient Israelites, probably right after the fall and destruction of the city and the temple of Yahweh by the Babylonians in 586 BCE.16

The earliest sacred sites associated with pilgrimage were probably located in the south, in those imprecise areas where Yahweh was thought to come from, particularly Seir and Edom. No explicit mention is made in the Hebrew Bible of pilgrimage to Mt. Sinai/Horeb, the place of Yahweh’s major theophany. Our earliest secure sources, the eighth-century BCE prophets Hosea, Amos, and Micah, knew Yahweh’s deliverance of the people of Israel from Egypt and the wanderings in the desert, but do not provide precise geographical references of the itineraries (Hwang 2013; Dearman 2013). The only person who is said to have returned to the holy mountain is prophet Elijah, who travelled first from Beersheba a day’s journey “into the wilderness” and then effectuated a forty-day march to Mount Horeb (1 Kgs 19:3–4,8). The historicity of the Elijah’s narrative, probably originating in early-eighth century BCE Israel (Halpern and Lemaire 2010, 137–38), is suspect, but the story suggests that the desert south was known and visited by the Israelites during the monarchial period. It has been suggested that the camp stations of the Israelites on their way from Egypt to Canaan—recounted in Num 33:5–49—were no more than stops on the late Iron Age pilgrim routes to Mount Sinai (wherever this place was located) retroactively extrapolated to the Exodus’ times (see already Noth 1968, 243, 246). Others have understood them as stops in the trade routes of the Negev and Edom (Finkelstein 2015), although both options should not necessarily be mutually exclusive: comparative material from later periods demonstrates that pilgrimage routes can trace their origins back to ancient trade roads (Petersen 1994, 49). The desert itineraries present in Num. 33:5–49 are traditionally attributed to the Priestly source (Davies 1983), but most treatments consider the information they contain as coming from pre-exilic times. The prevailing view is that these routes represent itineraries dating to the first millennium BCE, either the Iron Age (Noth 1968, 243, 246; Redford 1992, 408–22; Finkelstein 2015) or afterwards (van Seters 1994, 153–64; Roskop 2011).

Within this context, the site of Kuntillet ‘Ajrud is unique in its combination of a place where people purposely traveled and where cultic rituals where performed. Some scholars have related the site to the traditions concerning Mt. Sinai and Elijah’s travel (Mazar 1990, 449; Meshel 2012, 67), and certainly Kuntillet ‘Ajrud’s location away from the Darb Ghazza and with a meager water source was not primarily dictated by considerations to the main trade routes. Some fragmented wall plaster inscriptions found at the site can be related to the Exodus story and the Sinai theophany, including a hymn presenting imagery similar to the one associated with Yahweh’s theophany (Ahituv, Eshel, and Meshel 2012, Inscr. 4.2, 110–1; Na’aman 2011, 309–10) and another, much more broken, inscription interpreted as an early version of the biblical story of Moses (Na’aman 2011, 310–2). But even if Kuntillet ‘Ajrud was a place where Yahweh’s theophany was celebrated and where parts of the Exodus story circulated, its association with a presumed pilgrim route to Mt. Sinai is hypothetical. Its identification as a center of sacred travels is based on archaeology, not depending on presumed links with the Mt. Sinai tradition about which there is no clear-cut evidence. Kuntillet ‘Ajrud was likely part of a larger network of Iron Age sacred sites visited by passing travelers, such as the much smaller open-air shrines of Horvat Qitmit and ‘En Hazeva, of which we have only the most superficial evidence.

The practice of pilgrimage is one of the most archaeologically testable pieces of evidence of the influence of the southern heritage in the Israelite religion. In her landmark study on pilgrimage in the ancient Near East, McCorriston stressed the contrast between the practices of cult in Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and the Levant, originated in and intimately related to the secrecy of houses, and the open visibility of the commemorative sites of pre-Islamic Arabia (McCorriston 2011, 203–4). The open character of the rural cultic structures and tombs of the arid southern Levant and northern Arabia we have studied—standing stones, open courtyard shrines, cairns, high-places, and rock-shelter spaces—encouraged their periodic visiting and use for rituals such as sacrifices and feasts. In southern Arabia there is evidence of re-visiting and re-use of third millennia BCE tombs by people one or two millennia later (McCorriston 2013, 623), but such phenomena have not been extensively noted (and not purposively studied) in the arid southern Levant. However, three lines of evidence may suggest that the hundreds of Bronze Age (and earlier) rural monuments and tombs in the Negev, Sinai, and southern Transjordan were re-visited in the first millennium BCE: in several areas, such as in the central Negev highlands, the distribution pattern of Bronze and Iron Age sites overlaps to a great extent; the layout of the ritual installations known to date to the Iron Age is very similar to their Bronze Age antecedents; and the nomadic character of the largest part of the local population makes the identification of multi-period evidence from one site very difficult. It is hoped that a comprehensive study of the evidence of multi-period visits and uses of archaeological sites in areas of high-density settlement, such as the central Negev highlands, will provide more data on the practice of pilgrimage.

Yahweh and Metallurgy

Another feature possibly related to the southern folklore are the traditions linking Yahweh, or the worship of Yahweh, with metallurgy. It is not surprising that the ritual practices of the ancient populations living in the Negev, Edom, and Sinai, areas rich in minerals such as copper and turquoise ready to be mined, involved the worship of deities associated with mining and the underground, such as Hathor, coupled with the performing of metallurgical activities involving the use of fire. Biblical scholarship has focused on several biblical texts that could indicate a prominent role of metallurgy in the development of early Yahwism, particularly: 1) the role of the Kenites, seen as itinerant metalworkers par excellence, in the spread of Yahwism in Palestine (Sawyer 1986); 2) the representation in prophetic texts of the God of Israel and his dwelling characterized as made of copper (Ezek 40:3; Zech 6:1–6), or of Yahweh as being a smelter (Ezek 22:20) or creator of the copperworker (Isa 54:16) (Amzallag 2009); 3) the identification of metallurgical terminology in the biblical description of divine-related elements, such as the firmament, the celestial throne, the divine radiance, and Yahweh’s “jealousy” (for a detailed analysis, see Amzallag 2019, 7–8); and 4) the popularity of stories such as that of Moses and the bronze serpent (Num 21:8, called nehushtan in 2 Kgs 18:4). It is likely that the biblical authors were aware of the metallurgical connotations of this vast terminology, and some of it could have been inherited from early periods in the history of Yahwism. However, this is a heterogeneous body of biblical texts that are not easy to date nor to interpret. Most of them comprise material that dates to the post-exilic period, when copper exploitation in the Arabah mines has yet to be found, and thus their relationship with the formative stages of Yahwism should be considered as secondary until better contextualized evidence is found.17

Conclusion: The Southern Arid Margins and the Origin of Yahweh’s Cult

The long history of contacts during the Iron Age suggests a continuous flow of cultural traditions and religious beliefs between the ancient Israelites and the autochthonous southern groups, where both peoples influenced each other in a complex, multifaceted process. The different facets of the worship of Yahweh and other accompanying southern traditions were likely transmitted at different paces throughout this long period.

The Formative Period, ranging from the fourteenth to the eleventh centuries BCE, is characterized by the persistence of the same cultic elements that had been in vogue for centuries, now accompanied by the introduction of Egyptian or Egyptianizing cultic centers and cults, although adapted and reformulated according to the local practices. During this period, there is no evidence of contacts between the local semi-pastoral societies with the Israelite (or proto-Israelite) population settling down in the central highlands of Palestine, not to mention the transmission of religious ideas.

Biblical scholars supporting the Midianite-Kenite hypothesis have stressed the importance of the role of the southern mobile groups of the Early Iron Age, habitually seen as prosperous Midianite, Kenite, and even Amalekite caravan traders, on the genesis of the ancient Israelites in central Canaan (e.g., Cross 1983; Schloen 1993; Smith 2001, 145; Römer 2015; Na’aman 2016; Lemardelé 2019, 61). Most, if not all, of the evidence adduced is based on the analysis of biblical passages difficult to interpret (e.g., Gen 37:38: Num 31; Judg 5). However, archaeological evidence linking the Early Iron Age settlements in the central highlands of Canaan with the nomadic groups of the Negev and northern Hejaz is weak.

That the nomads had a significant role in the operation of the Early Iron trade is very likely, but they can hardly have impacted the socio-economy of Palestine considerably. Their area of migrations, inferred mostly from the geographical distribution of the ceramics they produced and used (Negevite pottery and QPW), was restricted to the arid regions south of the Beersheba Valley (Tebes 2013, 75, fig. 16, 113, fig. 20). This would agree with such evidence as we have for their metal-related activities in the Arabah.

The southern nomads presumably had a mining industry of their own, but the finds of copper/bronze artifacts and metallurgy in the Early Iron Age southern Levant are restricted to three workshops in the northern Negev and Sinai and three in Canaanite urban centers in the Jordan and Jezreel Valleys (Tebes 2013, 54, fig. 5; see also Yahalom-Mack et al. 2014; Gottlieb 2018), while the metal items were probably brought via the Jordan Valley and the King’s Highway and not central Palestine. The conclusion is that, while the Early Iron southern trade had a significant impact on the Negev and the Palestinian Canaanite towns, it was not of much significance for the population settling in central Canaan at that time.

It is only in the Early Contact Period, from the tenth to the mid-eighth centuries BCE, during the early phase of the northern colonization of the Negev, when the southern cultic practices began to be known and adopted by the population of central Canaan. The overall archaeological evidence indicates that this is the earliest period in which continuous contact and two-way flows of cultic beliefs between the northern newcomers and the peoples living in the Negev occurred. It is in this moment, not before, that we should date the beginning of the transference of southern elements to the Israelites, if not the worship of Yahweh itself. The process of contact was slow and multifaceted, with the northern, more settled Negev more prone to hybridity than the southern, more fringe desert regions. A new society, heterogeneous and multicultural, began to emerge, at first in the sites founded or re-settled in the Beersheba and Arad Valleys, and only later in the arid countryside.

Can this model take into account the biblical and epigraphic evidence of the beginning of the worship of Yahweh in ancient Israel? Circumstantial biblical evidence indicates that the ascension of Yahweh as the god of Israel can be linked with Saul’s adoption of Yahweh as the patron of his state. According to van der Toorn, Saul’s choice was not unexpected, coming as he was from a family of southern Gibeonite/Edomite pedigree (van der Toorn 1996, 281–86). Following this reasoning, the support given by the nascent state to Yahwism, continued later by the Davidic dynasty (see Smith 2002, 153–55), explains the rapid rise of the southern cult and its earliest epigraphic visibility in the Mesha stela, vis-à-vis its lack of visibility in non-state records.

In the Late Contact Period, from the late eighth to the mid-sixth centuries BCE, the adoption of foreign cultic practices went parallel with the emergence of the south Arabian trade that linked the areas west and east of the Wadi Arabah and the immigration of southern Transjordanian population in the Beersheba Valley and probably in areas further north. It was precisely these two factors that created the socio-historical background for the mixing of Judaean and southern Transjordan population, and with it the two-way exchange of historical memories, religious traditions, and cultic practices. The archaeological evidence demonstrates an accelerating process of hybridization of the Negev society since the late eighth century BCE, giving the Judaean population full access to the southern Transjordanian ‘Edomite’ folklore (see Frevel 2018). It is likely that the Judaean families and the Transjordanians began mixing each other, sharing ideas, folklore, rites, and deities; at the same time, the Judaean population mentally accommodated the absorption of the new neighbors through their incorporation into their own lineages, translating the new situation into the language of kinship. This period coincided with the highest development of the state in Judah, with a concomitant growth of a full-blown administrative and cultic apparatus and an increasing level of literacy, particularly around the state and temple bureaucracy. It was probably within this sociohistorical background that the so far oral traditions of the southern origin of Yahwism, as well as parallel traditions linking Judaean clans, families, and characters with southern Transjordanian ‘Edomite’ folklore (above all the conflation of the stories of the Israelite Jacob and the Edomite Esau), were written down in the sacred narratives that were to become the Hebrew Bible (Bartlett 1977; Tebes 2013, 137–51).

While the general dynamics of the process of transmission of Yahwism can be understood, its nature, phasing, and features are a matter of conjectures, more so when the cult of Yahweh as we know it is the result of several centuries of evolution in Palestine, with the old southern traditions being adapted, combined, and re-configured with other Syro-Palestinian elements.

References

Adron, Faried, and Matthias Müller. 2017. “The Tetragrammaton in Egyptian Sources — Facts and Fiction.” In The Origins of Yahwism, edited by Jürgen van Oorshot and Markus Witte, 96–103. Beihefte Zur Zeitschrift Für Die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 484. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Aharoni, Yohanan. 1974. “The Horned Altar of Beer-Sheba.” Biblical Archaeologist 37: 2–23.

———. 1981. Arad Inscriptions. Judaean Desert Studies. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

Ahituv, Shmuel. 1984. Canaanite Toponyms in Ancient Egyptian Documents. Jerusalem: Magnes Press.

Ahituv, Shmuel, Esther Eshel, and Ze’ev Meshel. 2012. “The Inscriptions.” In Kuntillet ‘Ajrud (Ḥorvat Teman): An Iron Age II Religious Site on the Judah-Sinai Border, edited by Ze’ev Meshel, 73–142. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

Al-Ayedi, Abd E. R. 2007. “The Cult of Hathor as Represented on the Stelae at Serabit El-Khadem.” Bulletin of the Egyptian Museum 4: 23–28.

Amzallag, Nissim. 2009. “Yahweh, the Canaanite God of Metallurgy?” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 33: 387–404.

———. 2019. “The Religious Dimension of Copper Metallurgy in the Southern Levant.” In Isaac Went Out … to the Field (Genesis 24:63). Studies in Archaeology and Ancient Cultures in Honor of Isaac Gilead, edited by Haim Goldfus, Mayer I. Gruber, Shamir Yona, and Peter Fabian, 1–13. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Anati, Emanuel. 1999. “The Rock Art of the Negev Desert.” Near Eastern Archaeologist 62: 22–34.

———. 1968–1974. Rock Art in Central Arabia (Expédition Philby-Ryckmans-Lippens en Arabie). 4 vols. Louvain: Institut Orientaliste.

Astour, Michael. 1979. “Yahweh in Egyptian Topographical Lists.” In Festschrift Elmar Edel: 12 März 1979, edited by Edgar B. Pusch, 17–33. Bamberg: M. Görg.

Avner, Uzi. 1984. “Ancient Cult Sites in the Negev and Sinai Deserts.” Tel Aviv 11: 115–31.

———. 2001. “Sacred Stones in the Desert.” Biblical Archaeology Review 27 (3): 30–41.

———. 2002. “Studies in the Material and Spiritual Culture of the Negev and Sinai Populations, During the 6th–3rd Millennia BC.” PhD diss., Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

———. 2014. “Egyptian Timna — Reconsidered.” In Unearthing the Wilderness: Studies on the History and Archaeology of the Negev and Edom in the Iron Age, edited by Juan Manuel Tebes, 103–62. Ancient Near Eastern Studies Supplement Series 45. Leuven: Peeters.

Avni, Gideon. 1994. “Early Mosques in the Negev Highlands: New Archaeological Evidence on Islamic Penetration of Southern Palestine.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 294: 83–100.

———. 2007. “From Standing Stones to Open Mosques in the Negev Desert: The Archaeology of Religious Transformation on the Fringes.” Near Eastern Archaeologist 70 (3): 124–35.

Axelsson, Lars E. 1987. The Lord Rose up from Seir. Studies in the History and Traditions of the Negev and Southern Jordan. Coniectanea Biblica, Old Testament Series 25. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International.

Bartlett, John R. 1977. “The Brotherhood of Edom.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 4: 2–27.

Beck, Pirhiya. 1982. “The Drawings from Horvat Teiman (Kuntillet ‘Ajrud).” Tel Aviv 9: 3–68.

———. 1995. “Catalogue of Cult Objects and Study of the Iconography.” In Ḥorvat Qitmit: An Edomite Shrine in the Biblical Negev, edited by Ithzak Beit-Arieh, 27–208. Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology 11. Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University.

———. 2012. “The Drawings and Decorative Designs.” In Kuntillet ‘Ajrud (Ḥorvat Teman): An Iron Age II Religious Site on the Judah-Sinai Border, edited by Ze’ev Meshel, 143–203. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

Bednarik, Robert G., and Maheed Khan. 2005. “Scientific Studies of Saudi Arabian Rock Art.” Rock Art Research 22 (1): 49–81.

Beherec, Marc A., Mohammad Najjar, and Thomas E. Levy. 2014. “Wadi Fidan 40 Mortuary Archaeology in the Edom Lowlands.” In New Insights into the Iron Age Archaeology of Edom, Southern Jordan: Surveys, Excavations, and Research from the University of California, San Diego & Department of Antiquities of Jordan, Edom Lowlands Regional Archaeology Project (ELRAP), Vol. 1, 665–721. Monumenta Archaeologica 35. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press.

Beit-Arieh, Ithzak, ed. 1995. Ḥorvat Qitmit: An Edomite Shrine in the Biblical Negev. Ithzak. Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology 11. Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University.

Ben-Arieh, Sarah. 2011. “Temple Furniture from a Favissa at ‘En Ḥaẓeva.” ‘Atiqot 68: 107–75.

Benoist, Anne. 2007. “An Iron Age II Snake Cult in the Oman Peninsula: Evidence from Bithnah (Emirate of Fujairah).” Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 18: 34–54.

Benoist, Anne, Sophie Pillaut, and Matthias Skorupka. 2012. “Rituels associés au symbole du serpent en Arabie orientale au course de l’Âge du Fer (1200–300 avant J.-C.): l’exemple de Bithnah (Émirat de Fujairah).” In Dieux et déesses d’Arabie. Images et representations. Actes de la table redonde tenue au Collège de France (Paris) les 1er et 2 2 octobre 2007, edited by Isabelle Sachet and Christian R. Robin, 413–22. Orient & Méditerranée 7. Paris: De Boccard.

Bienkowski, Piotr, and Eveline J. van der Steen. 2001. “Tribes, Trade and Towns: A New Framework for the Late Iron Age in Southern Jordan and the Negev.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 323: 21–47.

Blenkinsopp, Joseph. 2008. “The Midianite-Kenite Hypothesis Revisited and the Origins of Judah.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 33: 131–53.