On Deserted Landscapes and Divine Iconography

Iconographic Perspectives on the Origins of YHWH

In light of three important trends and developments within recent research—first, the interpretation, the dating and the literary growth of the second commandment (Exod 20:4 ‖ Deut 5:8); second, the reevaluation of ancient Israel’s origins; and, third, the continuously increasing archaeological and iconographic record—the article surveys potential representations of YHWH from pre-exilic and post-exilic times in order to evaluate them against the background of YHWH’s origins. Without aiming at a clear identification of YHWH imagery, the study analyses a broad range of iconographic material: anthropomorphic and theriomorphic figurines, the motif of “the lord of the ostriches,” a cult stand from Taanach, the Bes-like figurines on the drawings from Kuntillet Ajrud, humanoid figures on a sherd from a strainer jar, the motif of an enthroned deity on a boat, the so-called horse and rider figurines and a famous Yehud coin depicting a deity on a winged wheel. Based on this evidence, it will be argued that the iconographic data can and should be included as a verifying or falsifying perspective into the discussion about YHWH’s origins. In order to fulfill this function, the iconographic evidence has to be studied without a specific religious-historical reconstruction in mind. Instead, the full range of possible interpretations and the polyvalent character of the imagery in particular should be taken into account.

ancient Israelite religion, aniconism, iconography, YHWH imagery

Introduction

In the last decade, the question of YHWH’s origins became a (renewed) hotspot within the history of religion as evidenced by several recent monographs on this issue (see Fleming 2020; Flynn 2020; Lewis 2020; Miller II 2021; Pfitzmann 2020). With only few exceptions (see also Lewis 2016), these studies do not engage in iconographic perspectives of YHWH’s origins but focus on biblical and extra-biblical texts instead. This phenomenon is not surprising at all, since ancient Judaism was—and to some degree still is—believed to be tightly connected (from its beginnings) to aniconism or at least aniconic tendencies.1

Already in ancient historiography, the prohibition of images was considered one of the most distinctive features of Judaism. In his Histories Tacitus writes, “[…] the Jews conceive of one god only, and that with the mind alone: they regard as impious those who make from perishable materials representations of gods in man’s image; that supreme and eternal being is to them incapable of representation and without end. Therefore they set up no statues in their cities, still less in their temples […]” (Tacitus, Hist. V, 5). In accordance with this, the idea of an encompassing aniconism characteristic unique to ancient Israelite religion was more or less undisputed within former biblical scholarship.

Thus, the question of iconographic perspectives on YHWH (or his origins in particular) was either never raised or quickly disregarded as jejune. But the former consensus of the ban of images as a theological cornerstone of the Hebrew Bible, which is not only an old tradition but practice as well, has been shattered in recent scholarship by three major developments on different levels of argumentation: first, the interpretation, the dating and the literary growth of the second commandment (Exod 20:4 ‖ Deut 5:8) and other Pentateuchal texts prohibiting the production and the use of cultic images; second, the reevaluation of ancient Israel’s origins; and, third, the continuously increasing archaeological and iconographic record.

With regard to literary criticism, the biblical ban on images is not only questioned in its interpretation regarding the images it relates to, but more importantly, in its dating. Even though biblical scholarship is still far from a consensus in detail,2 Hebrew Bible scholars came to realise that the second commandment is not to be understood as a general prohibition of images, but has to be analysed in view of the multifaceted image terminology provided in the biblical texts (Exod 20:4 ‖ Deut 5:8; Exod 20:23; 34:17; Lev 19:4; 26:1; Deut 4:15–28*; 27:15) and within its complex literary growth (see Uehlinger 2019). It is important to realise that these texts concern material cultic imagery (Kultbilder) exclusively and do not pertain to verbal imagery/metaphors (see Hossfeld 2003, 12) or the general way a deity was envisioned (see Ornan 2019). In light of the numerous and various divine images in the archaeological record (see below) and considering the “old” question of whose images are actually banned in the biblical texts, it is important to distinguish heuristically between images of YHWH and those of other gods (see Frevel 2003a, 35). Especially in the Exodus version of the decalogue it is evident that the prohibition against making cultic images (Kultbilderverbot) and the prohibitions against the worship of other gods (Fremdgötterverbot) are two separate commandments (Exod 20:3–5).3 When applied to the biblical texts in a diachronic perspective, this differentiation might have significant implications for the understanding and impact of the ban on images: If the prohibition is applied to images of other gods, it might hint at the existence of YHWH images. But if it is understood to relate to YHWH images, it rather stresses an aniconic conception of YHWH. However, most biblical scholars consider the prohibition of images in Exod 20 a rather late literary stage of the Hebrew Bible than previously assumed, evolving in exilic times at the earliest. That being said, a general aniconism in ancient Israelite religion cannot be deduced from or justified by pointing at the existence of the biblical traditions.

As far as religious history is concerned, recent scholarship has shown that a social group called “Israel” did not emerge outside the (promised) land, but is the result of complex social processes within the cultivated land (see Frevel 2018a, esp. 73–79). If Israel originated mostly autochthonously within and from Canaan, the religious history of ancient Israel has to be examined as a part of the history of religions of the Ancient Near East as a whole or more precisely of Syro-Palestine. In fact, “Israelite and Judahite religion/s are increasingly viewed as subsets of West Semitic religion; they may have differed in details of practice and belief from the religion of their neighbours […] as much as they shared many common assumptions with them” (Uehlinger 2019, 105). Instead of claiming an essential distinctiveness of Israelite and Judahite religion/s, current scholarship rather focuses on aspects of diversity and regionalisation (see Frevel 2016). Considering the indigenous character of ancient Israelite religion (see also Coogan 1987), Israelite aniconism cannot be explained by hinting at its distinctiveness anymore. As was concluded by Christoph Uehlinger, “YHWH was probably worshipped in ancient Israel and Judah under various forms and representations, among which are anthropomorphic and theriomorphic statuary in some places, and non-figurative material representations in others. In this regard, the local, regional and institutional varieties of his cult would not have differed much (and certainly not in essence) from that of any other major deity in the Southern Levant” (2019, 110). Against this background, the relevance and significance of images within ancient Israelite religion must be stressed anew.

From a methodological point of view, the discussion on (an-)iconism in ancient Israel changed not only due to the insight that the image ban is not to be understood in a general sense, but also due to the still increasing archaeological and iconographic data which attests to a great prominence and significance of images in ancient Israel/Palestine.4 The relevant materials from the Bronze and Iron Ages include, among others, steles, statues, figurines, plaques, amulets and seals. The images depict objects, phytomorphic, theriomorphic and anthropomorphic figures, hybrid creatures, deities, etc. In accordance with the quantity and new availability of iconographic data, the interpretation of ancient Israel’s symbol system evolved into a distinct method in its own right (see Keel 1992).

Although these trends and developments are not directly connected to the question of YHWH’s historical origins, they have a significant impact on the way we approach and reconstruct the history of religion of ancient Israel including the beginnings of Yahwism. As far as the historical provenance of YHWH is concerned, former and recent scholarship finds itself in a stalemate situation with two main religious-historical models which “differ not only in what concerns the space and time of YHWH’s emergence, but also with regard to the relevant sources and the corresponding profile of YHWH” (Leuenberger 2017, 160–61; emphasis in original). While one camp of scholars argues for a non-autochthonous origin, with YHWH coming from the South (i.e., the South Palestinian-Edomite area of the Arabah; see Leuenberger 2010, 2017; Leuenberger and Meyer-Blanck 2016), the other one opts for a northern origin (be it either in the area of Northern Syria or, with smooth transitions, in the north of Israel; see Pfeiffer 2005, 2017). As was pointed out by Christian Frevel, both hypotheses try to conform to the biblical texts, and both have argumentative weaknesses. He concludes, “As a result, it can be stated that in the question of the original worship of YHWH, the origin from the South still has a certain plausibility, but cannot be decided unambiguously and reliably” (2018b, 24).5 As a consequence, he suggests to differentiate between the origins (Ursprung), the provenance (Herkunft) and the beginnings (Anfang) of Yahwism(s) (see Frevel 2018b, 38). This differentiation adds a meaningful heuristic and methodological tool to recent debates which corresponds better with the complexity of religious-historical processes in ancient Israel.

With the above-mentioned “new” complexity of the origins debate in mind and under consideration of Israel’s questionable distinctiveness with regard to (YHWH) images, this essay seeks to reevaluate iconographic perspectives on YHWH’s origins.6 While former approaches often studied the iconographic evidence in order to substantiate an already formed hypothesis—be it YHWH either coming from the South or the North—or to argue for possible aniconic tendencies of YHWH’s origins (see Keel 1992, 1993, 2001), iconography is taken into account in its own right and as a complementary corrective to the presumed religious-historical reconstruction. Moreover, it has to be pointed out that the objects which operate under the label of YHWH imagery within scholarly debate do not form a homogenous iconographic group but rather present a conglomeration of various aspects and profiles linked to YHWH. As will be shown beforehand, these subtle presuppositions are (also) driven by the question of YHWH’s origins.

Against this background, the present essay surveys potential representations of YHWH in order to evaluate them against the background of YHWH’s origins. It is important to note that this study neither presumes nor aims at verifying a specific hypothesis on YHWH’s origins. Instead, it seeks to explore potential representations of YHWH in a longue durée perspective and their possible links to the origins, the provenance and the beginnings of Yahwism. The guiding question is as follows: (How) Can the iconographic evidence contribute to the debate on YHWH’s origins? The material discussed here includes objects from pre-exilic and post-exilic times to give justice to the variety, polyphony and dynamic of potential representations of the Israelite God. Since a clear identification of YHWH imagery is neither intended in this essay nor possible due to the characteristics of ancient Near Eastern iconography (see below), it goes without saying that the guiding question must and will remain open. The contribution of the following remarks is not to be seen in a clear identification of YHWH imagery but rather in its explicit methodological reflection. The argument will proceed as follows: First, I will elaborate on some basic presuppositions of this essay. Second, I will survey the alleged YHWH imagery from pre-exilic and post-exilic times, before elaborating on the methodological and religious-historical results of my study and their implications for YHWH’s origins in a third and final step.

Methodology and Presuppositions

Before dealing with the iconographic material, a few remarks are in order with regard to the underlying methodology and presuppositions:

- Aniconism vs. iconism in ancient Israelite religion: One of the most important studies dealing with Israelite aniconism has been provided by the learned Swedish scholar Tryggve Mettinger (see 1995).7 In his comparative analysis entitled “No Graven Image?” he aims at presenting a broader Near Eastern (West-)Semitic context for the aniconic tradition in ancient Israel by pointing at the Israelite masseboth cult. In contrast to many previous studies lacking such precision, Mettinger’s study is based on specific definitions. Most importantly, he distinguishes between “de facto traditions” and “programmatic traditions” of aniconism. While de facto traditions are indifferent to icons and, thus, tolerate aniconism, programmatic traditions are characterised by the repudiation of images, iconophobia and iconoclasm. Drawing on the definition provided by Burkhard Gladigow (see 1988), Mettinger uses the term “aniconism” as referring to cults without an iconic representation of the deity (anthropomorphic or theriomorphic) serving as the central cultic symbol. Instead, these cults evolve around either an aniconic cult symbol (so-called material aniconism) or sacred emptiness (so-called empty-space aniconism).

Correlating these definitions with the archaeological and iconographic data, I would like to highlight three relevant aspects:

First, when analyzing (an)iconic tendencies within ancient Israelite religion, a sharp distinction between aniconism and iconism does not do justice to the evidence at hand. In many cases, the attribution of an object to an iconic or an aniconic cult is rather difficult, since the definitional boarders are hard to establish and are closely related to the definition of “image,” “representation,” “symbol,” “emblem,” etc. (see Ornan 2005). Furthermore, the archaeological and iconographic data of ancient Israel/Palestine attests to a fluid transmission and an unproblematic coexistence of iconic, partly iconic and aniconic elements and cults. As was pointed out by Angelika Berlejung, a sharp distinction between the iconism and aniconism of a cult disregards the cultic reality in Antiquity, according to which the function of a marker of divine presence was more important than its visual appearance (see Berlejung 1998, 2009, 2017). Mettinger’s ideal-typical dichotomy between iconic and aniconic cults constitutes a strong antagonism between cultic images and standing stones or masseboth. Considering such objects as, for instance, the basalt stele from Bethsaida (Fig. 1), this antagonism becomes rather problematic. In addition, based on biblical and archaeological evidence it is a given that cult images and masseboth can be similar in function and/or their concept of marking divine presence. As was recently argued by Christoph Uehlinger, “an analytical terminology built on dichotomies and normative alternatives (as implied by both ‘image ban’ and ‘aniconism’) is […] rather unhelpful to explain the phenomena and controversies […]. An alternative approach should rest on concepts and a theoretical framework that overarches, or encompasses, so-called aniconic and iconic ritual regimes, allowing to analyse them with the very same questions regardless of their apparent antagonism” (2019, 122).

Second, the differentiation between de facto and programmatic traditions is also problematic, since it intermingles biblical and archaeological perspectives. While the de facto tradition can be deduced from the archaeological data only, the same does not hold true for the programmatic tradition, which relates to the biblical prohibition of images. In addition, it is important to note that the archaeological data does not correspond to the idea of a programmatic tradition. There are no clear archaeological signs of iconophobia or iconoclasm within ancient Israelite religion.8 Furthermore, it is questionable whether programmatic aniconism is a logical consequence of a previous existing de facto aniconism, as is implied by Mettinger’s differentiation.

Third, aniconic or iconic traditions within ancient Israelite religion cannot be transferred a priori from household religion or local/regional cults to the official cult and vice versa. Just to give one example: Even if the (aniconic) standing stone(s) from the local sanctuary in Arad (see Herzog 2002) are to be linked to YHWH worship, this does not prove that the official cult in Jerusalem was aniconic as well. In fact, it does not even prove that the cult in Arad as a whole was aniconic. Each archaeological and iconographic data must be analysed for itself and within its specific cultural, religious-historical and cultic traditions. This holds true especially for the different iconographic traditions of Yahwism in the North and South of ancient Israel/Palestine, which should be first and foremost examined in their own right and against their specific traditio-historical development. In addition, it is necessary to distinguish between cultic images depicting a deity and being used in a cultic context (Kultbild) and images of deities (Götterbild) (see Frevel 2003a; Uehlinger 1991). Not every image of a deity is necessarily a cultic image. The distinctive difference between these kinds of images is not their iconography, but rather their context(s) and, more importantly, their function(s).9

- An anthropomorphic cult statue in the first temple of Jerusalem: Since the beginning of the above-mentioned developments and trends within biblical scholarship, more and more scholars have been inclined to assume the presence of an anthropomorphic cult statue in the first temple of Jerusalem. Without going into too much detail, I would like to highlight the three most important lines of argumentation within this debate:

The first line of argumentation aims at the concept of temple cult and images: Stressing the analogy to other Ancient Near Eastern temples, Herbert Niehr called attention to the fact that the temple was considered the house of YHWH, in which he resided as humans did in their own houses (see Niehr 1997). According to Niehr, this concept goes in line with an anthropomorphic mode of speaking about the divine presence, including the care and the feeding of the deity represented in his statue (see also the second line of argumentation below). Therefore he presupposes “the existence of a ‘normal’ ancient Near Eastern cult,” which “implies the existence of a cult statue of YHWH as the main god venerated in the Temple of Jerusalem” (1997, 74, see also 2007).

The second line of argumentation, also brought up by Niehr, calls attention to several expressions in the Hebrew Bible which seem to indicate the existence of an anthropomorphic cult statue of YHWH (see Niehr 1997). According to Niehr, the most significant one is “seeing God’s face […]” (Ps 11:7; 17:15; 27:4, 13; 42:3; 63:3; 84:8), which in his view attests to an anthropomorphic cult statue within the Holy of Holies of the temple of Jerusalem. Furthermore, he refers to the act of clothing YHWH (see Isa 6:1; 63:1–3; Ezek 16:8; Dan 7:9; Ps 60:10; 108:10) and the so-called “bread of the presence” (see Exod 25:30; 35:13; 39:36; 1 Sam 21; 1 Kgs 7:48; 2 Chr 4:19), which present acts of caring for the deity residing in the temple. However, it has to be underlined that the biblical expressions in question could also be understood without assuming an anthropomorphic cult statue, namely as anthropomorphic language (see Mettinger 2005, 491). To put it with Nadav Na’aman: “Verbal anthropomorphic expressions that appear in the Bible, and appear to presuppose the existence of YHWH’s image in the temple, can hardly prove anything” (1999, 392). In addition, an anthropomorphism or an anthropomorphic concept of God does not necessarily imply an anthropomorphic cultic statue (see Frevel 2003a).

The third line of argumentation, brought up by Christoph Uehlinger (see 1997, 1998), is based on an analogy between the official cult of Samaria and the temple of Jerusalem. The argument goes as follows: If the cult of Samaria was iconic, then the same is most probably true for Jerusalem, because both are local forms of the same Yahwism. The idea of the existence of anthropomorphic cult statuary in Samaria is based on Assyrian texts and reliefs that are believed to refer to Assyrian spoliation of divine images from Samaria. Among others, Uehlinger refers to a relief from the king’s palace in Nimrud showing the removal of divine statuary from Gaza by Tiglath-pileser III and Sargon II’s Nimrud prism inscription mentioning the removal of divine statues as booty from Samaria (“the gods in whom they trusted, I counted as spoils”). Despite this Assyrian evidence it is by no means without controversy whether the cult of Samaria included an anthropomorphic statue of YHWH. The mentioned textual source is under suspicion because it may depend on other textual sources. Furthermore, the Akkadian word for “gods,” ilāni, does not give any information about the nature of the objects and whether they are iconic or aniconic.10 However, even if an iconic cult in Samaria could be proven, it becomes difficult in light of the administrative, (socio-)political, and cultural differences between Israel and Judah to draw conclusions from the cult of Samaria about the cult of Jerusalem.

In sum, neither the biblical nor the extra-biblical evidence can settle the question of an anthropomorphic cult statue in the first temple of Jerusalem with certainty. In the end, one is left with a non liquet, especially since the Hebrew Bible does not contain a single explicit reference to a cult statue of YHWH in the Jerusalemite temple. The assumption of a (very consistent and persistent) damnatio memoriae is tempting but speculative in the end.

- Ancient Near Eastern iconography and the question of a YHWH iconography: Especially in comparison to deities like El and Baal who are linked to particular pictorial types and constellations (see below), it is striking that YHWH does not seem to have a genuine iconography. Instead, YHWH seems to disappear or to be absorbed by the pictorial types and constellations of the cultivated land (see Frevel 2019). To put it with the words of Sakkie Cornelius, “[t]he million-dollar question that remains is whether the chief Israelite deity may be identified in the iconographical record” (2008, 99). Despite the growing iconographic material from Israel/Palestine, there are no depictions of deities that can be clearly identified as pictorial representations of YHWH. This lack of clear YHWH imagery as such is neither surprising nor telling, since Ancient Near Eastern iconography does not aim at a personal identification of deities, but rather at the (re-)presentation of divine types, attributes and aspects (see also the debate about the identification of the so-called Judean Pillar Figurines with the goddess Asherah). In addition, the usual way of identifying specific deities within the visual material, which is based on the deity’s theological profile and area(s) of competence as derived from textual evidence, is particularly difficult in the case of YHWH in twofold respect: first, the dating of biblical texts is highly disputed; second, there are several uncertainties with regard to YHWH’s (original) profile which, furthermore, underwent considerable changes in the course of the religious history of ancient Israel/Palestine. As was pointed out by Angelika Berlejung, “If YHWH successively took on the theological traits, competencies, and epithets of other deities over the course of the first millennium B.C.E., as is assumed by a majority of scholars and can also be deduced from the Hebrew Bible, this would at least raise the possibility that YHWH also did this in relation to these deities’ iconographies, paraphernelia, attributes, and symbolism” (2017, 74). Considering this complexity, dynamic and intertwining of religio-historical developments—especially as far as YHWH’s theological profile and his relation to El and Baal are concerned—current research still lacks a sustainable criteriology which does justice to the polyvalence of the images on the one hand and their specific religio-historical contexts on the other. Moreover, as far as (clear) identification is concerned, academic research is still far more influenced by textual/epigraphic than iconographic evidence. When combining the question of YHWH imagery with the origins of the Israelite God, another methodological remark is in order: It has to be pointed out that iconography and origins of a deity are not necessarily closely interrelated. The pictorial representations of deities do not necessarily aim at depicting their origins. Thus, it is not possible to directly and exclusively extrapolate YHWH’s character or profile from his origins to his iconography and vice versa. Such an approach is in danger of being a circular argument in both directions: When YHWH is believed to be an Edomite God, it would be rather problematic to look for YHWH imagery within the Edomite symbol system only. On the other hand, Edomite iconography with a link to YHWH does not necessarily prove YHWH’s Southern origin. The interrelation between iconography and origins is far more complex and rather situated on a “secondary” level of argumentation.

Also in light of and in response to this methodological challenge, the following study is not grounded in the methodological approach called iconographic exegesis (see de Hulster, Strawn, and Bonfiglio 2015), which is the use of visual data in the textual analysis of the Hebrew Bible. Instead, it focuses exclusively on iconographic evidence as one of various sources for the reconstruction of Ancient Near Eastern history. Despite many possible text-image-relationships, Ancient Near Eastern art is understood here as a partially autonomous system of symbols, that exists alongside the linguistic/textual system of symbols. Without presenting a comprehensive methodological approach here, I would like to highlight a few methodological basics that are essential for the following study (see Pyschny 2019): As a source, images have an important value in their own right. As archaeological, epigraphic and textual evidence, they require interpretation which should be based on a media-internal methodology. Only afterwards can the evidence be correlated as one part of a larger puzzle with other sources. Images do not offer an all-encompassing or even objective portrayal of historical events or developments. When using images as a historical source, one must take into account their validity and limits. Furthermore, one must consider how ancient societies used images for the depiction and interpretation of history. Images have a relative illustrative character based on conventions of representation. In addition, images can represent complex (chronological, local, social, etc.) relations simultaneously in two dimensions. Like texts, images have their own vocabulary or motifs (semantics), a distinct constellation or style (syntax), and a specific function or purpose (pragmatics). Ancient Near Eastern images do not generally aim at one-to-one portrayals but can be considered as representations of particular conceptual constellations.

A Survey of (Alleged) YHWH Imagery

With the above-mentioned methodological framework in mind, the following remarks present a survey of (alleged) YHWH imagery in chronological order spanning from the (late) Bronze Age/Iron Age I until the Persian period. Without any claim to being exhaustive, the following catalogue focusses on the most important objects and intentionally includes a variety of possible material in order to hint at specific problems of former and to a certain degree recent scholarly debate. Due to the restricted scope of this essay, the survey does not deal with symbols or masseboth linked to YHWH. However, a thorough analysis of (an)iconism within ancient Israelite religion would have to include not only this kind of evidence, but also, for instance, the tendencies of solarization within Iron Age glyptic. Due to the limited frame of an article, such an endeavor cannot be aspired in this context.

YHWH as an Anthropomorphic Deity

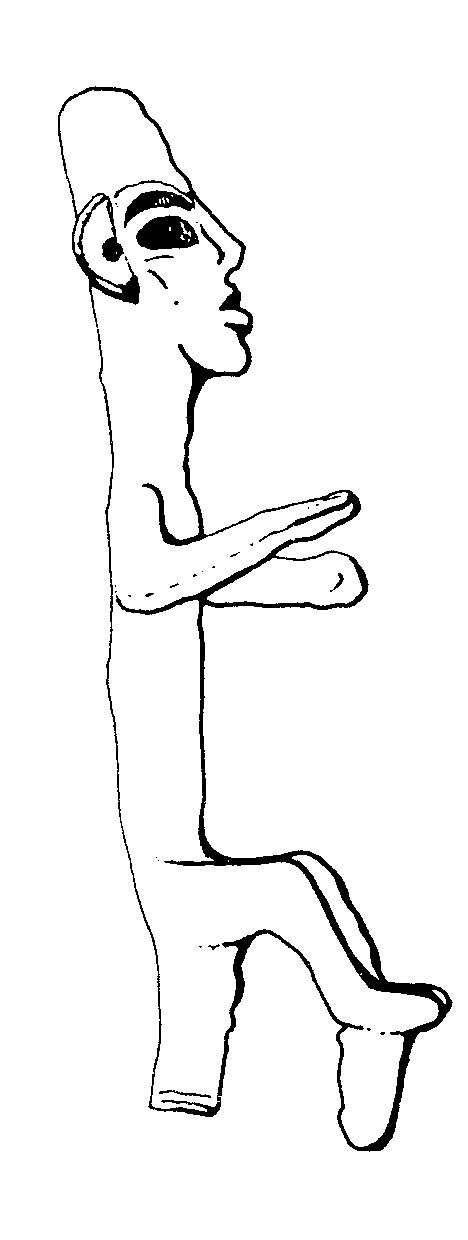

Within scholarly discussion, several (metal) statues from the Iron Age I and II are linked to YHWH imagery. These statues, some of which are also known from the (late) Bronze Age, are attested in two types. Using a small bronze figure from Hazor as example (Fig. 1), the El type can be described as follows: It depicts a seated male figure with a conic headgear and arms stretched out to the front. While one hand might have held a cup or a scepter, the other one seems to be raised in a gesture of blessing. Iconography of this type clearly aims at aspects of kingship and blessing. The Baal type can be best described in reference to a small bronze statue from Megiddo (Fig. 2). It shows a standing male figure with headgear and a short skirt in a striding pose. His raised hand holds a weapon and the other hand a shield. The iconographic aspects of this type evidently highlight aspects like dominance, physical strength and power.

Since both types show clear elements of divine iconography (e.g., headgear, blessing or striding posture), an interpretation as a (local) deity is plausible. An identification with YHWH, however, depends on the presupposed theological profile of the Israelite god. If he is considered a local manifestation of the weather god (Baal/Hadad), then the Baal type becomes a possible YHWH image (see Berlejung 2017). If he is believed to be connected to the blessing god El, the figures showing a seated male can be understood as YHWH imagery. It cannot be excluded as such that YHWH worshippers during the Iron Age might have recognised these images as representations of YHWH. However, from a methodological point of view, it has to be stressed that neither the El nor the Baal type attest to a specific YHWH iconography.

The Face of YHWH

Most recently, the catalogue of potential YHWH imagery received some new additions stemming from the early Iron Age II: an anthropomorphic clay head from Khirbet Qeiyafa, two similar clay heads (and two horse figurines) from Tel Moza, and two vessels from the Moshe Dayan Collection. Yosef Garfinkel, who links the various male heads to a new type of figurine from the tenth and ninth centuries BCE, considers them depictions of a deity, most probably the Israelite God YHWH (see Garfinkel 2020).

The clay head from Khirbet Qeiyafa is about 2 inches tall and shows prominent eyes, ears, a nose and a mouth (Fig. 3). The eyes were first attached to the face as rounded blobs of clay and then punctured to create the iris. The ears are pierced and the flat top is encircled by holes possibly signifying a headdress. The figurine was found inside a large, central building within the fortified city which has tentatively been identified as a palace. The four figurines from Tel Moza, two anthropomorphic and two zoomorphic, were found lying on the packed earth floor of a temple courtyard dating to the Iron Age IIA (see Kisilevitz 2015). All of them are hand-modeled with the same local Moza marl clay. The anthropomorphic heads, one of which clearly depicts a male (based on the puncturing on the chin that simulates a beard), show evident similarities in proportions, style, and production methods. Shua Kisilevitz describes the heads, which most probably belonged to free-standing figurines, as follows: “The figurines are fashioned ‘in the round’ out of a solid piece of clay onto which clay appliqués were attached to form the hair, headdress and facial features. The latter include a prominent straight-edged nose, large, bulky ears, and protruding eyes punctured in the centre to simulate the pupil. A prominent, pointed chin is evident in both figurines” (2015, 156). The two zoomorphic figurines depict harnessed animals, most probably horses. While one of these objects is a large hollow and burnished figurine showing the feet of a rider, whose body is not preserved, the other one is a smaller solid piece with traces of a rider or a pack at the back (see Kisilevitz 2016).

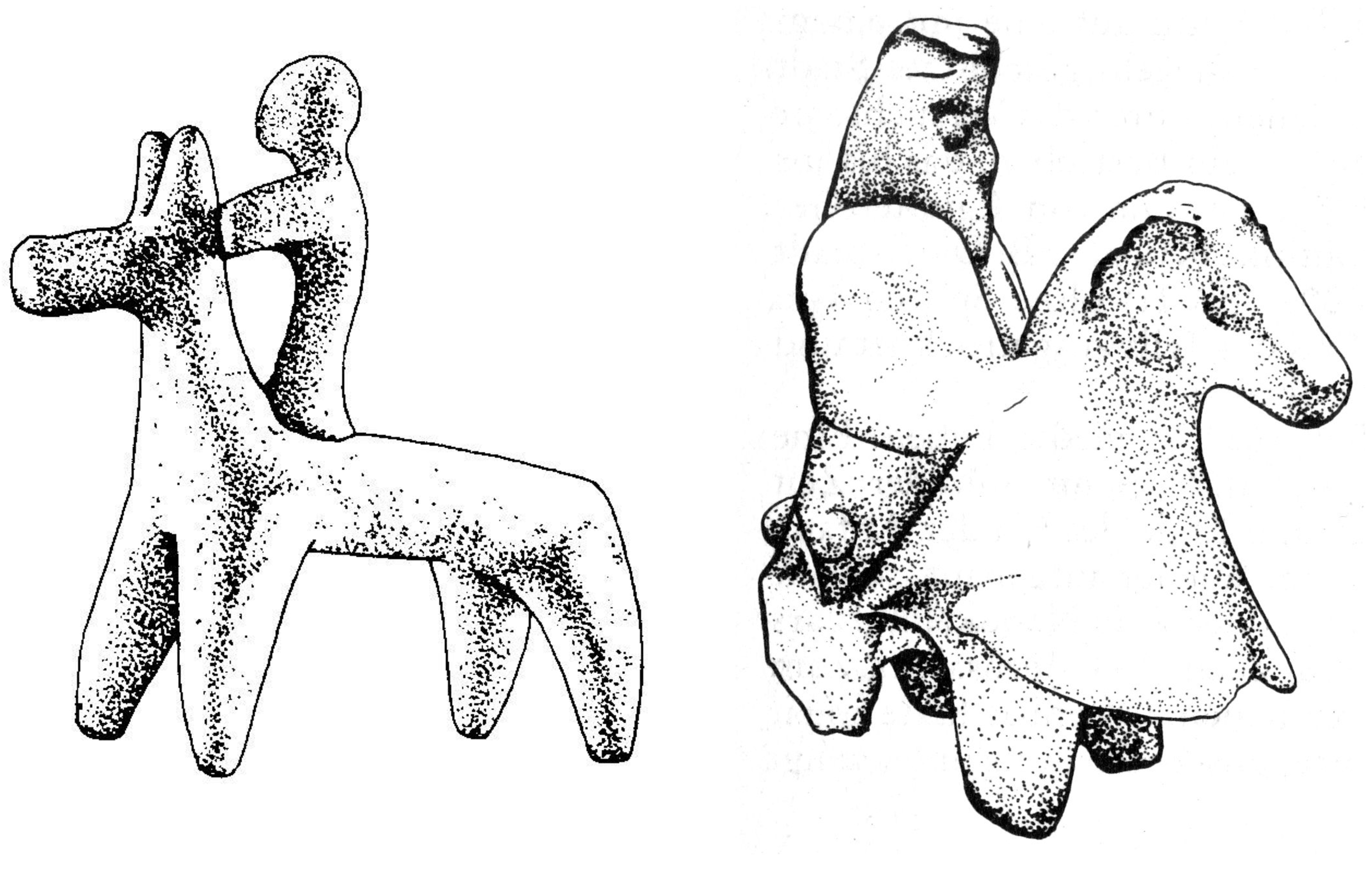

By linking the figurines from Khirbet Qeiyafa and Tel Moza together with regard to typology, style and iconography, Yosef Garfinkel interprets them as representing a horse and a rider. Moreover, he correlates their iconography with the biblical metaphors conceptualising YHWH as a rider in the sky or the clouds (see Deut 33:26; 2 Kgs 2:11–12; 23:11; Ps 45:4; 68:4; Is 19:1) and even understands Hab 3:8 as presenting YHWH riding a horse. In addition, the biblical expression “before the face of YHWH” (see, e.g., Deut 16:16; 1 Sam 1:22–23; Is 1:12) is believed to fit the figurines’ emphasis on the facial elements (eyes, ears, nose, mouth, beard), thus supporting the hypothesis of a unique iconographic type representing YHWH iconography.

In a critical response to Yosef Garfinkel’s hypothesis, Shua Kisilevitz, Ido Koch, Oded Lipschits, and David S. Vanderhooft convincingly outlined several problems and flaws in the argumentation with regard to the technological, typological, stylistic and iconographic remarks and interpretation (see 2020). For the purpose of this paper, it is not necessary to repeat all the detail-orientated counterarguments. Instead, the following remarks concentrate on the most relevant issues pertaining to the interpretation of the heads as the face of YHWH. First, it has to be pointed out that grouping the heads from Khirbet Qeiyafa and Tel Moza together overemphasises their typological, stylistic and iconographic similarities and disregards their differences. In addition, the connection of the heads to horses is by no means clear. This holds particularly true for the head from Khirbet Qeiyafa, where no equivalent horse figurine is preserved, and the connection is based only on the reference to the heads from Tel Moza and the vessels from the Dayan Collection. But even in the case of the Tel Moza figurines, the link between the heads and the horse figurines stands on shaky ground. Based on the proportions, there is no possibility that one of the heads could have been the rider of the smaller horse figurine. Second, the interpretation of the anthropomorphic figurines as representations of a deity is questionable at least. The figurines do not show clear divine attributes and the head from Khirbet Qeiyafa was not even found in a cultic context. A cultic context and an intrinsic religious nature are far more certain for the evidence from Tel Moza. However, considering the lack of divine markers and their similarity to clay figurines throughout the region, they cannot be assumed to represent a deity. Instead, they are most probably depictions of mortals and functioned as votive figurines. Even if one accepts the interpretation as deity, third, the link to a (specific) YHWH iconography is rather doubtful. These kinds of figurines are by no means restricted to Judean sites but also have parallels in ancient Philistia and in Galilee. Furthermore, to combine the facial features of the heads exclusively with YHWH (as the reference to the biblical expression “before the face of YHWH” implies) seems arbitrary and methodologically flawed as a whole, since it transfers biblical concepts of divine presence more or less directly to material culture. In addition, it has to be pointed out that the biblical texts do not present YHWH as riding a horse (not even in Hab 3:8!).

Thus, it is highly doubtful that the evidence from Khirbet Qeiyafa and Tel Moza is to be considered YHWH imagery. However, as will be shown below, the horse and rider imagery appears to be one of the most persistent trends within the discussion of YHWH iconography.

YHWH as a Bull

Since in Ancient Near Eastern iconography deities can also be represented by their symbolic animal, YHWH is quite frequently linked to bull iconography and symbolism (see Frevel 2000). To put it with the words of Silvia Schroer: “[…] one manifestation of YHWH was the bull”11 (1987, 74:95). This is not only due to the biblical texts which mention a theriomorphic cult image of YHWH in Bethel and Dan, but also to the prominence of bull iconography in ancient Israel/Palestine in the Late Bronze and the Iron Age I (see Keel 1992, 122:177). Interestingly enough, in these times bulls could be associated with deities of both types, the Baal or El type. Furthermore, bovines are by no means restricted to the Northern cult. However, as was argued by Berlejung, since the symbolism of the moon god Sin of Haran included bovine iconography, it might have been more prominent in the North also because of Aramean presence (see 2017).

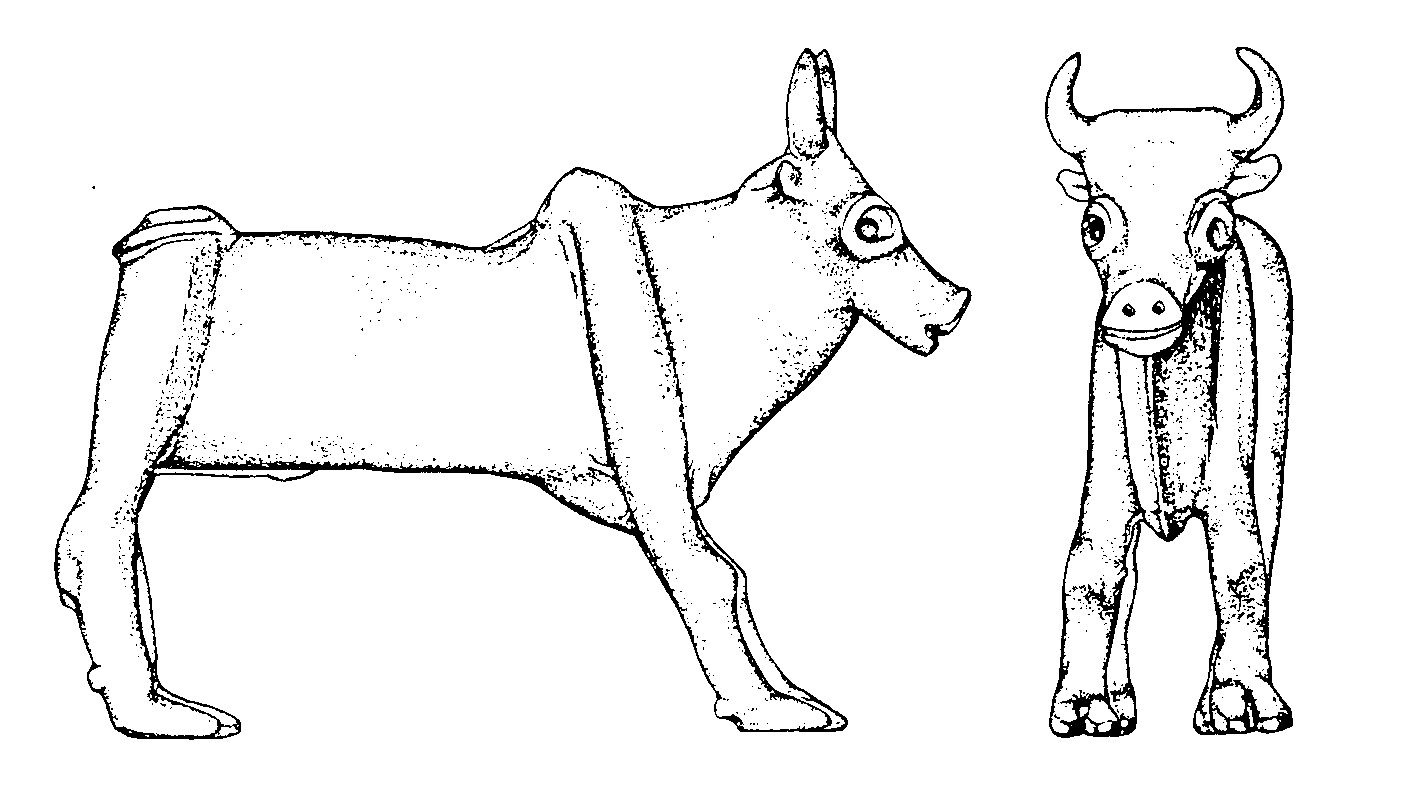

One of the most important objects to be discussed in this context is a bronze figurine found in 1978 at the so-called Bull-Site (Dhahrat et-Tawileh, east of Dothan) and dating to the Iron Age I. With a length of 17.5 cm and a maximum height of 12.4 cm it is one of the largest bronzes found in ancient Israel/Palestine (see Mazar 1982). According to its discoverer, it was found near the western stone wall of a cult site, most probably a regional open-air sanctuary. The figurine (Fig. 4) shows a zebu bull and is characterised by a tendency both towards naturalism (see the relation between the body and the head, the molding of the ears and horns and the details of the knees, ankles, feet and male organs) and towards schematization (see the rectangular shape of the body, the shape of the legs and of the lower part of the head). Based on the proportions of the figurine, it depicts a young animal rather than an old bull. The iconography evidently aims at highlighting aspects like youth, vitality, physical strength.

For the topic at hand, two questions have to be raised: First, what exactly does the bull represent? Is it to be understood as a symbol (Keel 1992, 122:134; Uehlinger 2001b), a pedestal (Ahlström 1990, 80; Hendel 1997, 218) or an attribute animal (Mazar 1982, 32)? Second, which deity might be associated with it? Neither of these questions can be answered with certainty. Since the bronze was not found in a defined context, archaeological hints at its possible use(s) are not present. In light of its remarkable size, especially in comparison to other bronzes, and its careful and high-quality production, it is most likely to be referred to as a cultic image. If this is correct, the bull is most likely to be understood as a symbol animal. In Israel’s environment, such as Egypt, the bull is by no means attested as a pedestal animal only, but also as an image of worship and gods. As far as the biblical texts are concerned, they seem to support the notion that the bull was understood as a YHWH image. As was argued by Klaus Koenen, “they do not in any way suggest a carrier animal, but rather explicitly designate the bull as a divine image“ (2003, 192:108).12 In the case of this particular bronze figurine, however, the interpretation as cultic image might be difficult, since it was found together with a standing stone. This raises the question about the relation between cultic image and standing stone, especially since both might have had the same function within a cult.

With regard to the second question, a research consensus can be discerned to the extent that the bull—in whatever form it may be present here (symbol, pedestal, or attribute animal)—can be regarded as a representation of the West Semitic weather god. Thus, Baal, YHWH and El are possible candidates for identification (Keel and Uehlinger 1992, 134:134; Coogan 1987, 2). In light of the “equation” of Baal, YHWH and El in the history of religion during the Iron Age I, a closer definition of the deity represented by the bronze figure is not possible without already presuming a specific religious-historical development. To put it bluntly: In Ancient Near Eastern iconography, the bull is a particular polyvalent symbol that cannot be exclusively linked to a specific deity. An interpretation as YHWH remains possible and likely though.

YHWH as the Lord of the Ostriches

Within scholarly debate, the motif of the “lord of the ostriches” can be considered one of the most acknowledged YHWH images. The seals or seal impressions in question show an anthropomorphic figure flanked by two ostriches (Fig. 5). The figure’s arms are either raised and directed towards the ostriches or are explicitly placed at their necks. Both gestures indicate the aspect of physical power and dominance. Following Othmar Keel and Christoph Uehlinger, this motif constitutes a thoroughly non-Egyptian version of the “lord of the animals” and replaced the Egyptian “lord of the crocodiles” in ancient Israel/Palestine, who already lost all of his particularly Egyptian attributes during the Iron Age I and appeared there as the “lord of the scorpions” (see 1992, 134:140). Depictions of the “lord of the ostriches” emerged in the Iron Age IIA and survived into the Iron Age IIB. They have been found scattered over the entire inland region of Israel and Judah: Tell el-Farah (North), Samaria, Gezer, Megiddo, Tel Rehov, Tell en-Nasbeh, Beth-Shemesh, Lachish and Tell Beit Mirsim.

Up to now, the “lord of the ostriches” plays a crucial role within the debate on YHWH’s Southern origins. Othmar Keel and Christoph Uehlinger (1992, 134:140) argue as follows:

“[…] the ‘Lord of the Ostriches’ is not the only indigenous deity in the iconography of Iron Age IIA, but it is the dominant one. The connection with ostriches points to the fact that the inhabitants thought of this deity as at home in the steppe region of Palestine—just like the god Yahweh, who originally came from southeast Palestine (northwest Arabia), the region that served as home for the Shasu. Yahweh is connected with Seir, Paran, Edom, Teman, Midian, and the Sinai in ancient texts and those that speak about what took place in antiquity, such as Judg 5:4f., Deut 22:2 or Hab 3:3, 7” (see also Keel 2007, 4, 1:205–6)

Jaroš proposed an identification of the figure with YHWH based on a specimen from Tell en-Nasbeh, which conforms to the above-mentioned iconographic patterns, but, in addition, shows a little disk on the right side close to the neck of the ostrich. Karl Jaroš interprets this feature as an abbreviation for the sun god Amun-Re or as a cryptographic abbreviation of YHWH’s name (see 1995). As a consequence, the motif is believed to depict YHWH as the sovereign ruler of the steppe and the guarantor of life despite the constant life-threatening horrors of the desert.

When sticking first and foremost to the iconography, it has to be pointed out that there is little or almost no reason to consider the figure as a deity in the first place. The motif does not show any divine attributes and could be interpreted as a human figure “in the conventional composition of a (probably) superhuman hero conquering menacing animals” (Beck 1995, 151). In regard to the object including the (sun) disk, it is in fact worth asking whether this suggests some general, numinous presence or is supposed to depict a particular solar deity. However, since the (sun) disk is not an essential feature of the motif, it cannot be decisive for the interpretation of all objects and in particular not for those without sun disk.

In any case, as far as the question of YHWH’s origins is concerned, it seems quite evident from the above-mentioned quotation that the “lord of the ostriches” cannot provide any positive evidence for YHWH’s Southern origins (see also Pfitzmann 2019). As was recently pointed out by Juan Manuel Tebes, “the identification of these figures with the cult of Yahweh has yet to be proven” (2017, 20). However, based on the “lord of the ostriches” motive, there can be no doubt that the imagery from the southern deserts had an impact on or influenced the religious symbol system of ancient Israel/Palestine during the later Iron Age (see 2017). Taken together with the above-mentioned biblical texts which are reminiscent of YHWH as God of the desert, an identification of the “lord of the ostriches” with YHWH becomes possible and probable. However, as argued by Fabian Pfitzmann (2019, 163) this iconographic motif does not prove YHWH’s origins from the South but rather attests to a local, i.e., southern, form of Yahwism in the context of pre-exilic polyyahwism.

The Invisible YHWH

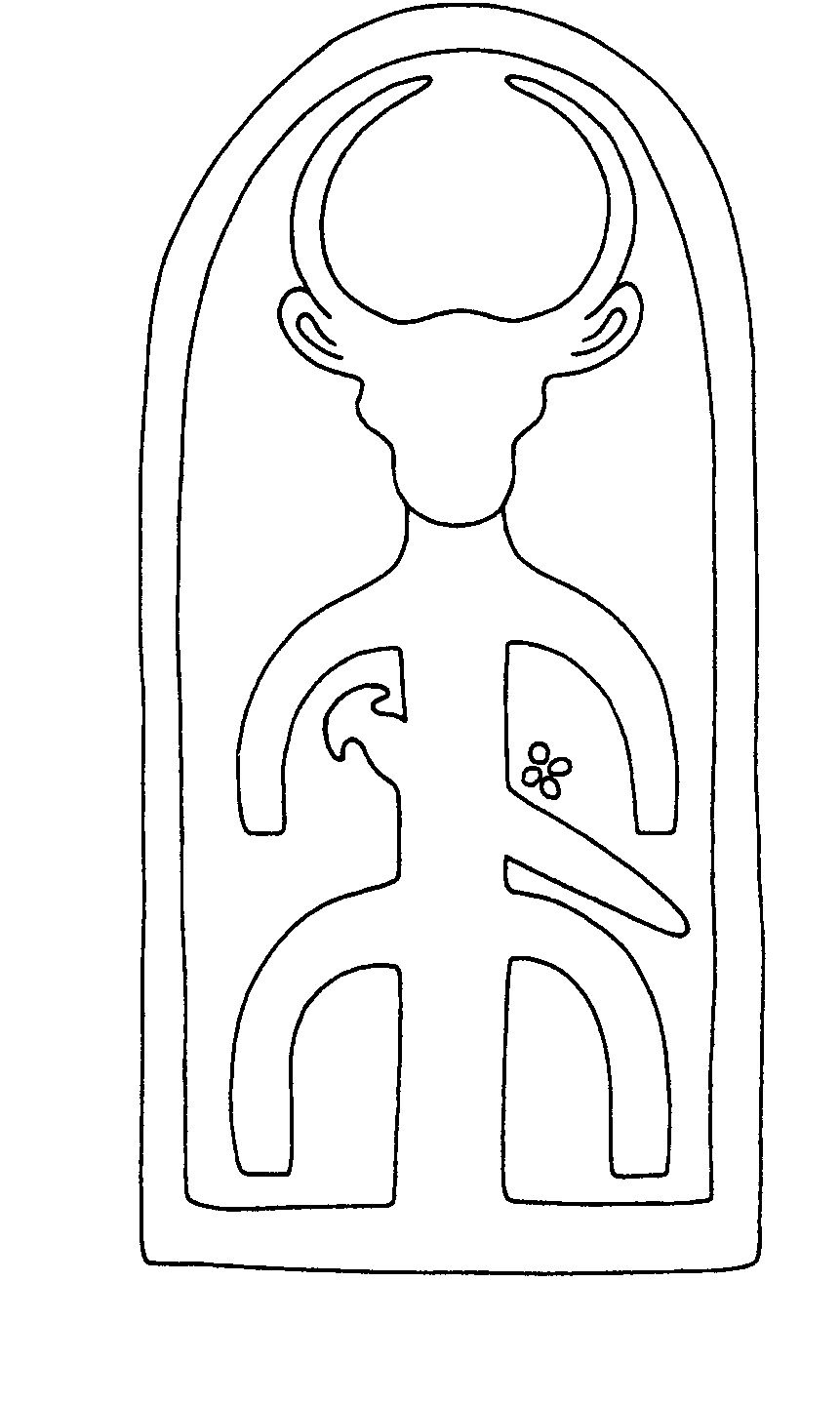

When it comes to alleged YHWH imagery, a cult stand from Taanach (height: 53.7 cm; width: 22 cm; length: 24.5 cm)—one of the most famous examples of terracotta cult stands in ancient Israel/Palestine—is a particularly interesting object (Fig. 6).

This four-tiered terracotta cult stand is believed to show two representations of YHWH. Found in a cistern protected by a layer of silt, the object dates to the Iron Age IIA and most probably belonged to the sphere of family and household religion (see Frevel 1995, 2:819–21, 2003b, 189–90; Kreuzer 2007; Zwickel 2007, 13–15). It has a rectangular shape and is hollow inside. While the first, second and fourth tiers have the same height, the third one is remarkably lower. The tier at the top is decorated with a double-lifted pastille pattern and forms a basin whose exact function is not certain. All tiers have a centre flanked by parallel design elements. The first tier features a nude woman or goddess depicted frontally, whose facial features and breasts are particularly highlighted. The figure stretches her arms out to two lionesses which flank her on the side. While the faces of the lionesses can be seen in the front of the stand, their bodies are visible in its sides. The female’s hands appear to grab or touch one ear of each lioness. The space between her and the lioness on her left side is almost entirely filled by an incised circle. The second tier shows two cherubs on either side directly above the lionesses. In between the cherubs there is an open space with slightly rounded corners. Both aspects, the cherubim and the well-carved empty space, support the impression of a guarded and protected entrance area (into a sanctuary). On the third tier, a tree with three pairs of volutes constitutes the centre. It is surrounded by two horned animals (caprids) nibbling at it. This scene is, furthermore, flanked by two guardian lionesses. The fourth tier displays a quadruped in profile, most probably a horse or a (bull) calf. A winged disk is carved above its back. This is the only tier whose centre is not flanked by theriomorphic elements, but by two volutes pointing outwards. According to Glen J. Taylor, this cult stand includes two representations of the Israelite god (see 1988, 1993). The first one can be detected in the second tier. The open space is understood as intentional and as a representation of YHWH as “YHWH of Hosts who dwells (among) the cherubim” (2 Kgs 19:14f ‖ Isa 37:16; Ps 99:1). Thus, the second tier is believed to depict an invisible or non-representable deity: “Consideration of the structure of the stand, its Yahwistic context, and its iconography, then, strongly suggest that tier three is an iconographic representation of YHWH of Hosts, the unseen God who resides among the cherubim, the earliest ‘representation’ of Yahwe known in the archaeological record” (Taylor 1993, 111:30). For Taylor, this interpretation is confirmed by the fourth tier. Interpreting the quadruped as a horse and based on the combination of horse and sun disc, he makes a connection to the biblical account of 2 Kgs 23:11, the consecration of horses to the sun in the entrance area of the Jerusalemite temple. In reference to this, he identifies the representation of the fourth tier as a solarised representation of YHWH.

However, there are several methodological/theoretical, textual and iconographic reasons why Taylor’s argumentation is not conclusive (see also Doak 2007): First, Taylor presumes and, in a way, overemphasises a Yahwistic context for the cult stand. This is supported by neither the actual archaeological context of the find nor its iconography. Second, Taylor’s interpretation of the cult stand and the identification of the deities are based on a rather speculative structure of the cult stand displaying a double representation or somehow a pair-constellation of YHWH (second and fourth tier) and Asherah (first and fourth tier). This idea seems to be influenced not by the cult stand itself, but rather by the finds of Kuntillet Ajrud (see below). Furthermore, the identification of the nude female as Asherah and her identification with the tree in the third tier is disputable at the very least (see Frevel 1995). Third, Taylor’s interpretation of the open space as a representation of YHWH does not take alternatives into account (e.g., window, protected entrance area and/or stylised sanctuary). The same holds true for practical or pragmatic reasons. To put it bluntly with the words of Berlejung: “[…] ‘window holes’ on cultic stands are nothing out of the ordinary. In the end, a gap must be able to remain simply a gap” (2017, 85). Fourth, the biblical references mentioned by Taylor cannot bear the weight of the argument. As already pointed out by Othmar Keel and Christoph Uehlinger the biblical phrase yōšēb hakərûbîm does not mean “who dwells (between) the cherubim,” but rather “who is enthroned on the cherubim.” Thus, strictly speaking the imagery of the cult stand does not correspond to the epithet. In addition, in the biblical account of 2 Kgs 23:11 the horses do not function as symbolic animals of YHWH. Without wanting to exclude the possibility of horses being symbolic animals of YHWH (see below), it is important to note that this cannot be restricted to YHWH exclusively and, even more importantly, cannot be proven by hinting at 2 Kgs 23:11.

Taking all arguments together, it seems rather unlikely that the cult stand from Tanaach displays any YHWH imagery. As will be shown in the next step, the same holds true for the drawings of Kuntillet Ajrud.

YHWH as a Bes-Like Figure

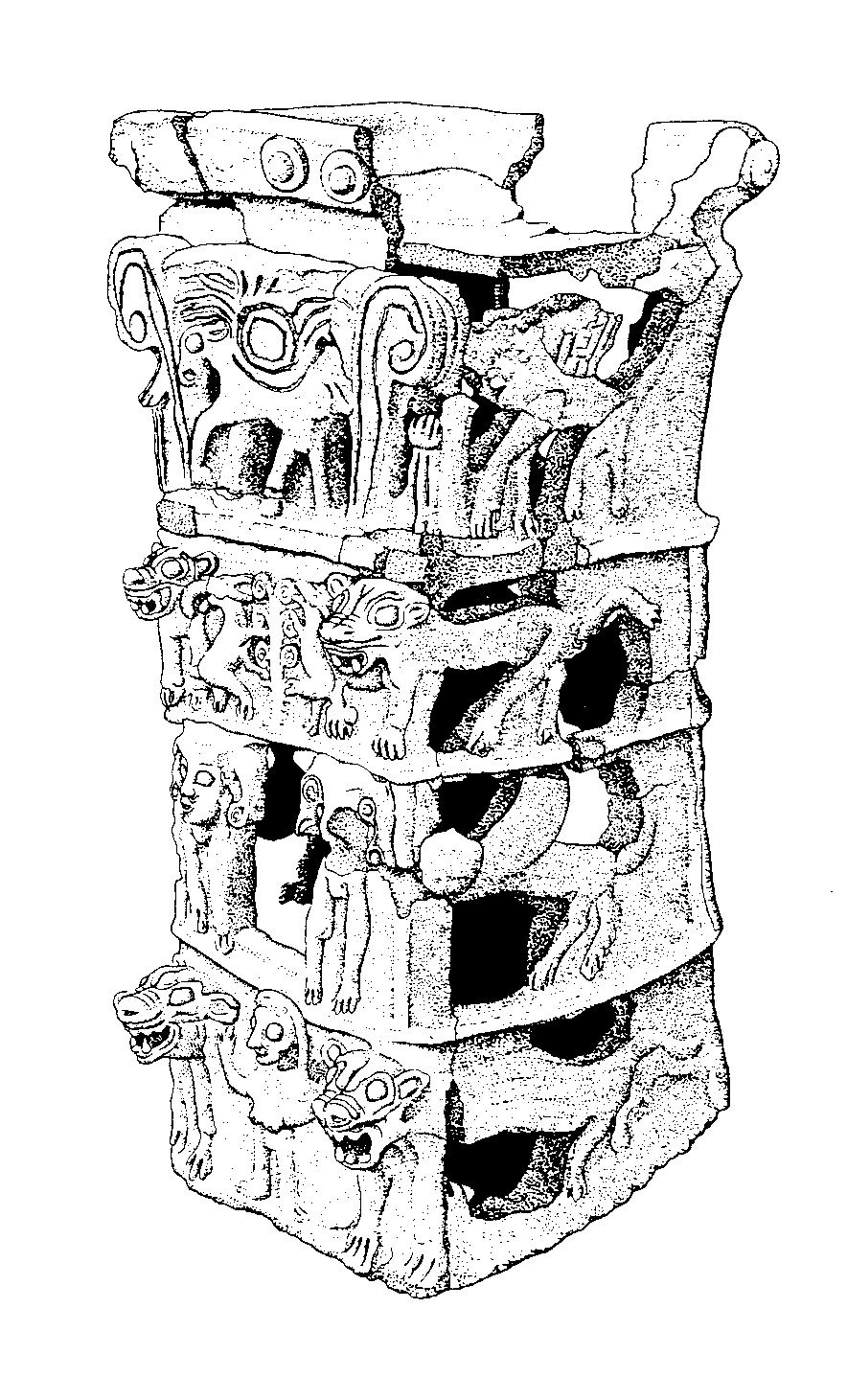

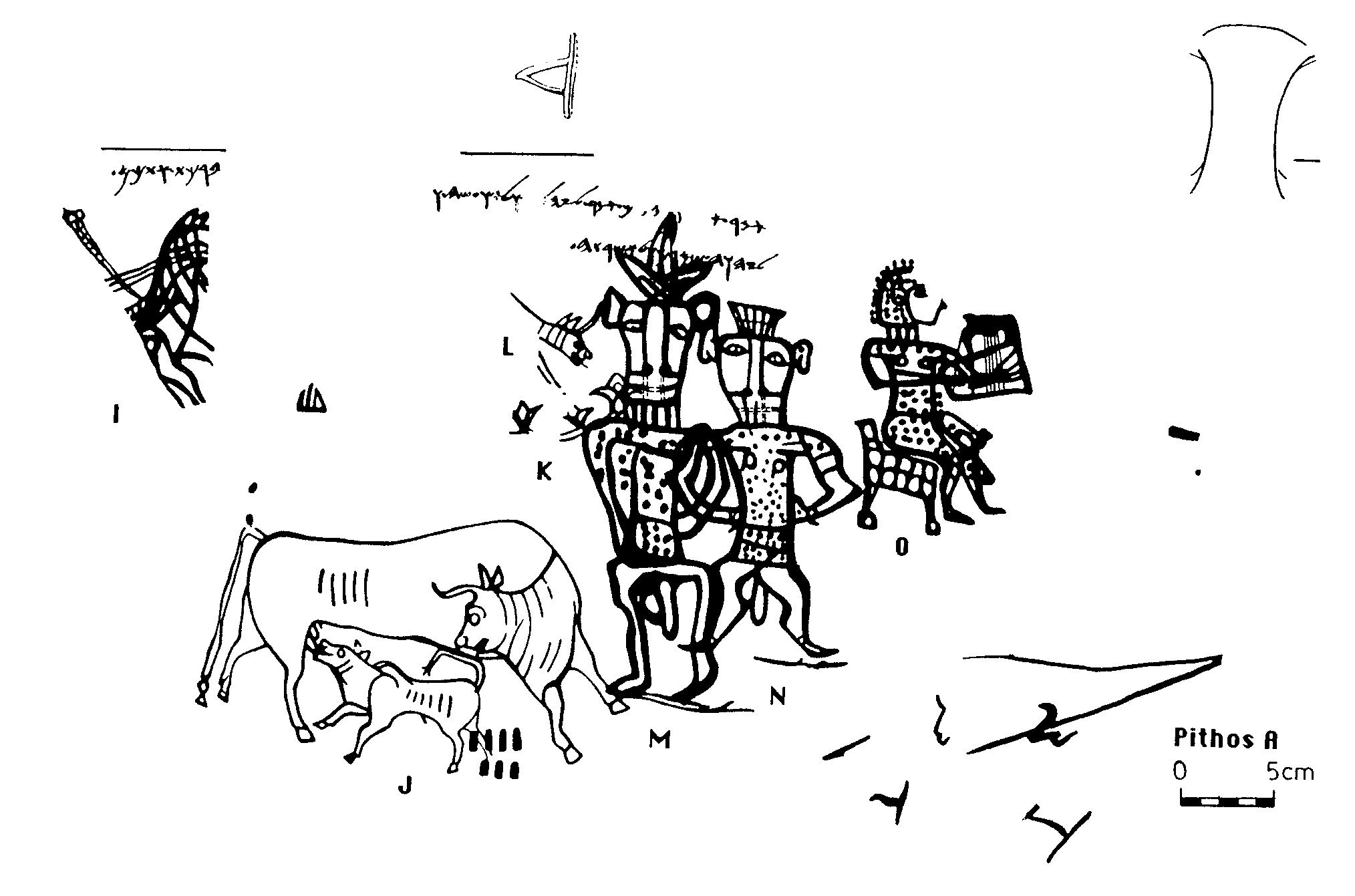

The finds of Kuntillet Ajrud not only changed the academic discourse with regard to the religious history of ancient Israel, but also significantly influenced the debate on YHWH imagery. This is in particular caused by the drawings of Pithos A (Fig. 7),13 which show, among other things, a harnessed horse, a suckling cow with calf, and above it, situated in relation to and feeding from a lotus tree, two Bes-like figures viewed frontally and a seated female lyre player. As this enumeration suggests and as is confirmed by a quick look at the drawings, the drawings do not present a coherent pictorial composition, but rather individual motifs which were placed paratactically next to or on top of each other.

For the discussion on alleged YHWH imagery, the anthropomorphic figures interpreted as Bes-like figures (see Meshel 2012) are of great importance. This fact is not necessarily due to their pictorial quality, but rather to the inscription above the larger figure reading “Speak to Yaheli, and to Yo‘asa, and to […] I have [b]lessed you to YHWH of Shomron (Samaria) and to his ʾasherah” (see Smoak and Schniedewind 2019, 5). Basically since the discovery of the inscriptions and drawings, the scholarly community has been divided over how to interpret the two crowned and vaguely anthropomorphic standing figures.

Mordechai Gilula was the first to doubt not only the interpretation of the figures as Bes representations, but also to establish a direct connection between the inscription and the two figures (see 1979). Based on the interpretation of the figures’ heads as cattle or bull heads depicted frontally and the interpretation of the p-shaped circles of the right figure as breasts, following the inscription he proposed an identification as YHWH and his consort Asherah. Gilula’s proposal is first of all highly problematic from a methodological point of view, inasmuch as he does not interpret the pictorial representations independently of the inscriptions but postulates a direct connection between inscription and drawings. With regard to methodology, the inscription and the drawings must be analysed separately and in their own right before the question of their possible connection(s) can be raised.

As far as the iconography is concerned, the two figures show no clear elements of bull symbolism as such. The headdress (presumably a feather crown), the grotesque-looking grimace face, the protruding ears, the tail or penis, the crooked O-legs and the frontal representation rather hint at Bes iconography (see Hadley 2000). Taking all these observations together, the affinities of the drawings are stronger towards Bes iconography than (hybrid) bovine features. The headdress or the feather crown corresponds rather to representations of Bes and does not really allow for an interpretation as horns. Moreover, none of the figures show hooves (see Frevel 1995, 2:874). In addition, Gilula’s basic prerequisite, namely the smaller figure being a female figure, is rather controversial. Even if one interprets the p-shaped circles as breasts, this does not oppose Bes iconography, since we find many androgynous representations of Bes in pre-Hellenistic times. Also considering the final excavation report, it is not possible to make definitive statements about the gender of the figure. As was argued by Othmar Keel and Christoph Uehlinger, “the two figures from Kuntillet ‘Ajrud are not to be treated as a heterosexual pair, in the sense of Bes and Beset, but it is rather more likely that they are two Bes variants, one masculine and one bisexual-feminized” (1992, 134:219). The fact that the drawings do not aim at a planned pair-constellation is underlined by the studies of Pirhiya Beck. She has convincingly shown that the right figure was drawn first, and only later, at a different height and partially overlapping the right figure, the left figure was added to the composition (1982). According to Beck, the inscription above the two figures, which possibly came from one hand, was applied only after the pictorial representations. Thus, from a diachronic perspective no direct connection between inscription and drawings, and thus also no YHWH imagery, can be inferred from the findings of Kuntillet Ajrud (see Frevel 1995, 2:856, 876; Uehlinger 1999b, 49).

In light of these insights, Brian B. Schmidt suggested understanding the hybrid creature on pithos A as a (and even the only legitimate) YHWH image (see 1995, 2002, 2016). His interpretation is based on the presupposition that the biblical ban of images does not oppose all forms of pictorial representation of deities, but explicitly prohibits only anthropomorphic and theriomorphic cult images. As a consequence, cult images in the form of a hybrid creature are not believed to be affected by the biblical texts. Thus, from the viewpoint of the biblical authors, hybrid creatures are the only legitimate way of representing YHWH. With this basic prerequisite in mind, Schmidt turns to the drawings of Kuntillet Ajrud. He neither denies the above-mentioned diachronic development of the figures (as far as their application is concerned) nor their identification as representations of Bes. Instead, he integrates these insights into his argumentation and correlates them with a Yahwist context using an analogy from literary criticism. As a consequence, he ascribes the inscription above the figures to a final editor who intended to identify the found drawing as YHWH and Asherah and who could consider them a legitimate pictorial representation of the Israelite god (and his consort) because of their form as hybrid creature. Schmidt formulates his conclusions as follows: “[…] the biblical writers recognized and embraced a cultic image of YHWH that was a Mischwesen of a composite made up of anthropomorphic and theriomorphic elements along the lines of the figures attested at Kuntillet ̔Ajrud” (Schmidt 1995, 103).

As innovative as this interpretation may be, it stands and falls with the presupposition that hybrid creatures are not integrated into the biblical prohibition of images. Without wanting to engage in the highly complex scholarly debate about the prohibition of images, I deem this notion rather questionable. Schmidt’s argumentation is also unconvincing from an iconographic point of view. Although the identification of the two figures as Bes-like figures should not per se exclude a connection with YHWH (and Asherah), the reverse idea—a link to YHWH (and Asherah)—cannot be postulated but has to be proven independently from the inscription. In this context, it is noteworthy that there is no evidence for a connection of YHWH with the iconography of Bes or hybrid creatures in Israel/Palestine except from Kuntillet Ajrud. Thus, the drawings would constitute the first and only instance of this iconographic phenomenon and, one cannot escape the impression that Schmidt’s argumentation runs the risk of being a circular argument. Independent of the question whether the analogy with literary criticism is fitting at all, Schmidt’s remarks are also inconclusive from this perspective. Why should a final editor who aims at linking inscription and drawings place the inscription partly on the figures, as is clearly shown by the overlapping of the left figure? The intended interpretation of the figures with YHWH and Asherah would have been more evident to others by placing the inscription above the figures.

In a recent article, Ryan Thomas reviewed the most important iconographic arguments for identifying the two standing figures as YHWH and Asherah (2016). By reevaluating the figures’ sexual dualism and their overlapping pose (both of which are believed to hint at a pair constellation as male and female partners), their Bes-like and bovine features and the larger iconographic context of the individual pithoi, the author seeks to provide “strong support for seeing an organic link between text and image on the pithos” and to shed “new light on the iconography of YHWH as it existed during the Israelite monarchy of the Late Iron Age” (2016, 123). Due to limited space, this paper cannot engage extensively with the detailed and well-argued remarks made by Ryan Thomas. Thus, the following comments focus on the most important aspects for the question at hand only and should not be taken as a comprehensive discussion of every single argument. First, it has to be pointed out that Thomas’ interpretation of the figures is based on and in a way driven by the assumed organic relationship between the inscription and the drawings. The imagery itself does not present any obvious connection to YHWH except for being positioned close to an inscription mentioning him. From a methodological perspective, one has to insist on interpreting the iconographic material in its own right before linking it with the inscription. Second, the interpretation of the figures as a (planned) pair constellation showing a smaller female figure behind a bigger male one is founded on the idea that both figures stem from the same artist, which is by no means evident. However, even if one does not accept Pirhiya Beck’s assessment, which explains the positions of the figures as a diachronic development (see above), there is one iconographic detail which stands in opposition to this interpretation: The right figure is not placed directly behind the left figure, as is often assumed based on the higher ground line on which it is situated. Since the elbow of the figure is clearly visible, it seems to run in front of the left figure’s chest, insinuating that the figures are positioned beside each other (Frevel 1995, 2:875 n. 621). Third, to consider the various pictorial designs and the inscriptions on pithoi A and B deliberate compositions “intended to function together to convey meaningful expressions of worship of YHWH” (Thomas 2016, 180) not only homogenises the diverse imagery but also interprets it exclusively in light of the inscription. Fourth, linking Bes (and Horus) symbolism distinctively to YHWH tends to overstress the iconographic material, ultimately making every Bes amulet a potential icon of YHWH.14 Such a conclusion seems rather problematic in religious-historical respect.

YHWH Striding over the Natural World

Another pair-constellation linked to YHWH and Asherah is to be found on a large sherd of an Iron Age II strainer (see Gilmour 2009). The object uncovered during the excavations at the Ophel in Jerusalem in the 1920s (Fig. 8) bears a pictorial design incised on the surface (8.43 cm wide and 6.55 cm high). It was discovered at the northern edge of the so-called stepped stone structure. Based on stratigraphic and typological observations, the vessel can be dated to the eighth century BCE. The pictorial design, which was cut into the sherd after the vessel was broken, probably dates to the same time. It shows two anthropomorphic figures, one female and one male, set upon a series of semi-circular lines. On the left, there is a female figure consisting of two triangles. While the upper triangle forms a face with eyes and eyebrows, a nose and a mouth in it, the lower triangle contains a small, inverted triangle below a dot most probably signifying the pubic area and the navel. To the right, there is a male figure taking the form of an inverted triangle with two legs extending downwards. A face including eyes and eyebrows, nose and nostrils, a mouth and a chin has been carved into the triangle. Furthermore, a semi-circle at the top might indicate some kind of hat or headdress. Both figures are connected in two places: by a line extending from one upper triangle to the other and by a line in the waist area of the male figurine. In the space between the figurines created by these lines, there is an X mark (tentatively interpreted as the letter taw by Gilmour), one of the lines of which cuts the edge of the lower triangle of the left figure.

Hinting at the naked frontal view with an emphasised pubic area (of the left figure) and the rounded headdress (of the right figure), Gilmour argues that the two geometric humanoid figures “are best identified as Yahweh and Asherah” (2009, 100), with the male figure representing YHWH striding over the natural world.

The interpretation of the pictorial design is complicated by the geometric/schematic style and the fact that humanoid figures in a triangular shape are not attested in the material culture of Iron Age Judah. However, based on the iconography, one is right to remain sceptical towards an identification with YHWH and Asherah. For starters, the interpretation as deities is by no means evident. To put it with the words of Theodore J. Lewis: “The sherd was not found together with a cultic assemblage or in any type of sacred precinct. There are no other clear markers of divinity (hairs, hairdo, garb, insignia, symbolic animal […]) and no inscriptional evidence (apart from what could be the letter taw)” (2020, 310). In addition, it is at least questionable whether the design aims at depicting a genuine pair-constellation. The lines of the figures differ in thickness, and their connections and positioning do not seem to be the centre of the pictorial constellation. Finally, it has to be pointed out that the interpretation of the semi-circles at the bottom of the sherd as a mountainous area is rather hypothetical and does not take the possibility of geometrical decoration into account. Taking all observations together, there is not enough evidence to link these humanoid figures with YHWH imagery.

YHWH in a Boat

When Gustav Dalman first published the seal of Elishama in 1906 (1906; see also Keel and Uehlinger 1992, 134:307–11), he advanced the idea that this seal displays a representation of YHWH as “lord of heaven” (Fig. 9). Since the seal clearly belonged to a man with a Yahwistic patronym, the god enthroned in the boat has to be identified as the Israelite god. The object in question is an Iron Age IIC seal made of a yellowish hard oval stone (dimensions: 18 mm long; 16 mm wide; 5 mm thick at the edge; 7 mm thick in the middle). The vaulted side, which is drawn by a simple line and divided into two parts by a double line, bears an inscription reading “to Elishama, the son of Gedaljahu.” For the question at hand, however, the almost flat reverse side, also crossed by a line, is of far more importance. It shows a boat whose end is formed by two long-necked bird heads. The boat holds a throne on which a male (probably bearded) figure with a wrinkled robe is seated. While his left arm is placed on his lap, the right forearm seems to be stretched out upwards. The figure wears headgear and is flanked by two elements that are either stylised trees or incense altars/stands. It was considered a forgery at first, until a great number of comparable objects, some of which stem from archaeological excavations, came to light. Based on this material, it can be considered a consensus of recent research that the (bearded) enthroned deity in a boat is most probably connected to the moon god. The boat symbolises the dynamic movement of the god from the gate of heaven and stands metaphorically for the crescent moon.

Even though the seal cannot be exclusively linked to YHWH, it has to be asked whether YHWH might have been worshipped as moon god in seventh-century Judah. From a religious-historical perspective, this might be possible. However, it has to be pointed out that the motif of the enthroned god in a boat is by no means restricted to Jerusalem or Judah, but is also attested, for instance, in Shechem, Beth-Shean or Jokneam. An exclusive identification as YHWH is therefore all the more problematic. In addition, one has to keep in mind that the theophoric element of the owner’s name is not necessarily linked to the seal’s iconographic decorations. The iconography itself is polyvalent and hints at the moon god and/or a blessing deity. A clear identification of the enthroned god in a boat is neither aimed at nor possible.

YHWH as a Rider

Considering the above-mentioned linkage of YHWH with horses, it does not come as a surprise that the so-called horse and rider figurines (Fig. 10) are considered representations of YHWH by some scholars.

The terracotta figurines of a man riding an equid became particularly prominent in the Iron Age IIC. Up to now, around 300 items are known (see Kletter 1999). According to Raz Kletter, the horse and rider figurines can be divided into four types, whereby only the first type represents a specific Judean variant of these terracottas. This type can be described as follows: “Type 1 consists of solid, simple figurines […]. The rider has a simple, handmade head, and stands on the back of the horse with hands glued to its head or neck. The horse has a simple muzzle, often painted with red or yellow, above whitewash, but without applied parts. Some of the riders have pillar bodies; others have narrow bodies, sometimes ending in little ‘stump’-like legs. The horse may have a curl or a disk on the head, but rarely […]. Even more rare are riders that carry a shield, made of an applied piece of clay” (Kletter 1999, 38). The items have been predominantly found in domestic contexts (see Uehlinger 2001a). Besides the so-called Judean pillar figurines, the horse and rider terracottas present the second most important group of figurines from Iron Age IIC Judah.

As usual when it comes to figurines, function, meaning and identification of the horse and rider figurines are disputed. The propositions within scholarly debate involve the interpretation as toys (Hübner 1992, 121:36), elite symbol (Cornelius 2007, 31), divine protector/mediator or representative of the “host of heaven” in the context of family or household religion (Uehlinger 2001a, 40) and a specific deity.15 Especially those figurines decorated with a disk are often interpreted in relation to 2 Kgs 23:11 and the “horses that the kings of Judah had dedicated to the sun” as symbols of a local sun god or YHWH (van der Toorn 2002, 62; Ornan 2005, 213:103). Assuming that the disk is to be understood as a sun disk, the figurines are interpreted as images of a solar-connoted YHWH (Ahlström 1970–1971). This line of argumentation is problematic since the interpretation as sun disk is at least questionable (e.g., forehead decoration). Furthermore, it is by no means evident that the figurines depict a deity. The latter was doubted by Sakkie Cornelius, among others, who points convincingly at the lack of divine attributes (see 2007). On the other hand, the interpretation as YHWH cannot be excluded as such—in fact it is worth considering in view of the popularity, the distribution patterns and find contexts of the horse and rider figurines. This holds true even more considering that the horse and rider figurines are also attested in Persian times16 (see Frevel 2013, 258–59; Cornelius 2014) and, thus, have a high degree of continuity in pre-exilic and post-exilic times.

YHWH on a Winged Wheel

The last object to be mentioned in this catalogue is the famous Yehud drachm (Fig. 11), which was found in Palestine around 1800 and is now under the ownership of the British Museum.

It is a silver coin with rather exceptional dimensions (diameter of 15 mm and weight of 3.29g) and dates into the fourth century BCE.17 The obverse shows a bearded male head facing to the right and wearing a crested Corinthian helmet. The reverse displays a bearded male figure in a square of cable-pattern. The figure’s upper body is nude, while hips and legs seem to be covered with a robe/garment. The figure is seated on a winged wheel facing to the right. The right hand is either wrapped in the garment or rests on his lap. The left holds a falcon or an eagle (see Blum 1997; Niehr 2003; Edelman 1995; de Hulster 2009, 2:198–205). In the lower right corner of the reverse a small bearded head, facing to the left, is recognisable, which is occasionally interpreted as the head of Bes or a satyr (Mildenberg 1979, 184; Niehr 2003, 123:209). More likely, it has to be interpreted as a human, possibly the Persian official who initiated the minting of the coin (Edelman 1995, 194).18 On the left and right side above the male figure, there is an Aramaic inscription whose reading is still under debate. In principle, the three letters could be read as yhd (“Yehud”) (Sukenik 1934, 178–80; Barag 1993, 265), the name of the Persian province of Judah, or yhw (“Yahu”), the name of the Israelite God (Gitler and Tal 2006, 6:230; Gitler 2011). Since both readings would attest to a link to Judah, this debate must not be settled in this context. Focusing on the iconography, it can be stated that the seated figure most probably represents a deity (Blum 1997, 18; Niehr 2003, 123:209). However, it is highly disputed which deity is portrayed. Within scholarly debate the propositions for identification include Zeus and/or Ba ̔altarz, Dionysos, Triptolemos, Hadranos and Ahura Mazda. Furthermore, many scholars argued for an identification with YHWH (Price 1975, 10; Meshorer 1982, 1, 25; Kienle 1975, 7:68–70; Edelman 1995, 204; Blum 1997, 24; Niehr 2003, 123:209). Before evaluating the iconography, it had to be stressed that the drachm is unique in many ways (see de Hulster 2009, 2:203–5). It is the only attested item of its kind, its dimensions are rather unusual for a local mint (but see the new Judean coin published by Gitler 2011) and also its imagery is without exact parallels. The above-mentioned date cannot be proven with certainty and is predominantly based on a specific typology of (Judean) coins. Since the exact finding location is unknown, the minting authority cannot be determined with certainty. In fact, the long-standing classification as Judean coin was recently challenged by Gitler/Tal (2006), who consider the coin a Philistian mint. The iconography itself as well as the image constellation of an enthroned, semi-nude, bearded deity holding a bird hints at a Zeus type or its oriental adaptation. The winged wheel could adhere to both, Hellenistic or oriental influence—if this differentiation is meaningful at all. Thus, no iconographic element of the coin necessarily indicates an identification with YHWH. However, especially in correlation with the inscription it seems plausible that the imagery of the coin might have been perceived as YHWH image.

Conclusions

Coming back to the guiding question of this essay of how iconographic evidence can contribute to the debate on YHWH’s origins, one is faced with a rather disillusioning picture. Although we discussed several “eligible” candidates for YHWH imagery, none of the items is a safe bet—not even the objects bearing inscriptions! It became evident that the origins of YHWH cannot be explored based on the iconographic material alone. The religious system of symbols of ancient Israel/Palestine does not aim at the identification of specific deities and, in addition, is highly polyvalent. Furthermore, the methodological struggle for finding more or less clear-cut criteria for identifying specific deities is far from over. Probably due to the extraordinary influence of the biblical ban on images on research history, this problem is particularly striking in the case of YHWH. Nevertheless, we face similar problems in the case of other deities as well (El, Baal, Asherah, moon god of Haran), where the issue appears to be clearer, but in fact is not.

However, the iconographic data can and should be included as a verifying or falsifying perspective into the discussion about YHWH’s origins. In order to fulfill this function, the iconographic evidence has to be studied without a specific religious-historical reconstruction in mind. The full range of possible interpretation and the polyvalent character of the imagery in particular should be taken into account. Based on the catalogue presented above, I would like to highlight three aspects that might advance recent scholarly debates on this topic:

-

Even though we (still) cannot determine YHWH imagery with certainty, it is important to note that there are several legitimate candidates that could be interpreted as YHWH images (e.g., anthropomorphic figures, lord of ostriches, bull-iconography, horse and rider figurines, deity on the winged wheel) and are at least worth considering. More importantly, there are ample images which might have been perceived as YHWH imagery, even though the iconography does not adhere to specific expectations about YHWH iconography, but rather follows Ancient Near Eastern conventions.

-

The group of the aforementioned potential YHWH images does not form a homogenous YHWH iconography. Furthermore, they do not attest to a clear-cut and linear development in diachronic respect, but show several local and regional tendencies. Thus, instead of looking for a characteristic YHWH iconography one has to search for local variations of (possible) YHWH imagery. As far as the debate on YHWH’s origins is concerned, it is interesting to realise that the objects related to the question of a specific YHWH iconography are by tendency far more related to Northern (anthropomorphic figurines, bull iconography, etc.) rather than Southern influence (lord of ostriches). This might be an accident due to the available data or it could hint at aniconic tendencies in or from the South. However, since the iconography of deities does not necessarily aim at depicting their origins one has to be careful about overstraining the evidence. Instead, the variety of potential YHWH imagery might give (further) testimony to local or regional Yahwisms not exactly in the origin of Yahwism but at least in its beginnings.

-

Since the potential YHWH images stem not only from pre-exilic, but also post-exilic times, the iconographic calls for a reevaluation of the impact of the biblical ban on images (and the underlying understanding of “Judean orthodoxy”) in the Persian period (see Frevel, Pyschny, and Cornelius 2014). One cannot escape the impression that the interpretation of Persian (and early Hellenistic) material culture is still influenced by rather problematic religious-historical presuppositions. Just to give two examples, I would like to hint at the interpretation of the horse and rider figurines and the silver drachm. While Ephraim Stern considers the horse and rider figurines from the Iron Age II as representations of YHWH, he rejects this interpretation for the items from the Persian period (Stern 1999, 252). And the YHWH image on the famous silver drachm is interpreted by Gitler/Tal (2006) as a production of Jews that disregarded the biblical prohibition of images. In both argumentations, the exile functions as a significant turning point for the (an)iconic traditions within ancient Israelite religion and one has to wonder whether this kind of sharp distinction really does justice to both the biblical and iconographic evidence.

List of Figures

- Fig. 1

- Keel/Uehlinger (1992): Fig. 394.

- Fig. 2

- Keel/Uehlinger (1998): Fig. 140.

- Fig. 3

- Keel/Uehlinger (1998): Fig. 139.

- Fig. 4

- Arrangement based on Kisilevitz et al. (2020), 38–39. (Photos Clara Amit, Courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority).

- Fig. 5

- Keel/Uehlinger (1998): Fig. 142.

- Fig. 6

- Keel/Uehlinger (1998): Fig. 162b–d.

- Fig. 7

- Keel/Uehlinger (1998): Fig. 184.

- Fig. 8

- Keel/Uehlinger (1998): Fig. 220.

- Fig. 9

- Gilmour (2009): Ill. 1. (Courtesy of the Palestine Exploration Fund, London).

- Fig. 10

- Keel/Uehlinger (1998): Fig. 306a.

- Fig. 11

- Keel/Uehlinger (1998): Fig. 333b and Keel/Küchler (1982): Fig. 625.

- Fig. 12

- Gitler (2011): Fig. 1 (Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum; Drawing © The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, by Pnina Arad).

References

Ahlström, Gösta W. 1990. “The Bull Figurine from Dhahrat et-Tawileh.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 280: 77–82.

———. 1970–1971. “An Israelite God Figurine from Hazor.” Orientalia Suecana 19–20: 54–62.

Barag, Dan. 1993. “Bagoas and the Coinage of Judea.” In Proceedings of the XIth International Numismatic Congress, Brussels, September 8th–13th 1991, edited by Tony Hackens, 53–64. Leuven: Seminaire de Numismatique Marcel Hoc.

Beck, Pirhiya. 1982. “The Drawings from Horvat Teiman (Kuntillet ’Ajrud).” Tel Aviv 9 (1): 3–68.

———. 1995. “Catalogue of Cult Objects and Study of the Iconography.” In Horvat Qitmit: An Edomite Shrine in the Biblical Negev, edited by Itzhaq Beit-Arieh, 11:27–197. Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University. Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University.