White Paper: The Käte Hamburger Kolleg (KHK) in Bochum as an Institute of Advanced Studies in the Humanities

The present White Paper is neither an academic publication presenting research results nor does it address a public outside the university field. Instead, we take this opportunity to talk about our experiences with the Käte Hamburger Kolleg (KHK) as a funding format. We hope that this might be useful for other scholars considering an application in this or a similar funding line. Still, we also wish to contribute, more generally, to the ongoing discussion on the role of Institutes of Advanced Studies in the German humanities and how excellent collaborative research in the humanities is best served by public funding lines. Since not only scholars are party to this discussion, the present text might also be of interest to actors in the fields of research politics and administration as well as to journalists working on these issues.

internationalization, research politics, Käte Hamburger Kolleg, Center for Religious Studies, third party funding

The Käte Hamburger Kolleg (KHK) in Bochum as an Institute of Advanced Studies in the Humanities

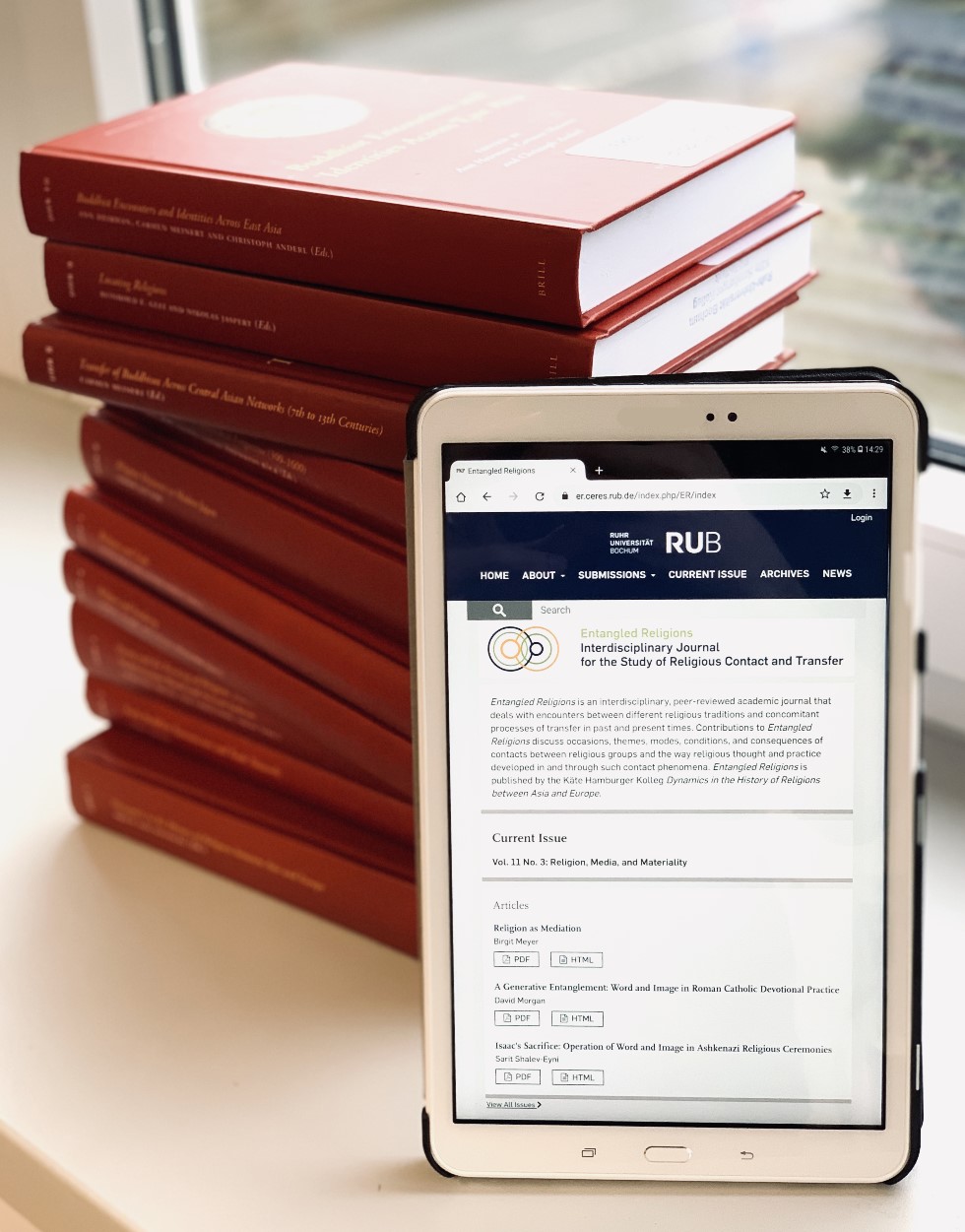

The Käte Hamburger Kolleg Dynamics in the History of Religions between Asia and Europe, which started in 2008 as the largest research project hosted by the Center for Religious Studies (CERES), Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Germany, entered its final working phase in April 2020. Thanks to the initiative of the Kolleg’s sponsor, the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, the Kolleg has been enabled to spend its remaining funds to focus, in this final stage, on dissemination. On the one hand, this includes the finalization of several academic publication projects, most notably in our book series Dynamics in the History of Religions (Brill Publishers) and our open access online journal Entangled Religions. On the other hand, we are taking the opportunity to present our work to a broader, non-academic public in the form of public talks, school labs, an exhibitions, and short films.

The present text belongs to none of these categories: It is neither an academic publication presenting research results nor does it address a public outside the university field. Instead, we take this opportunity to talk about our experiences with the KHK as a funding format. We hope that this might be useful for other scholars considering an application in this or a similar funding line. Still, we also wish to contribute, more generally, to the ongoing discussion on the role of Institutes of Advanced Studies in the German humanities and how excellent collaborative research in the humanities is best served by public funding lines. Since not only scholars are party to this discussion, the present text might also be of interest to actors in the fields of research politics and administration as well as to journalists working on these issues.

Internationalization

The funding line, later re-christened in honor of Käte Hamburger, was known, at its inception in 2008, as Internationale Kollegs für Geisteswissenschaftliche Forschung, which roughly translates to “International Research Consortia in the Humanities”. As the name suggests, this funding line is solely aimed at researchers from the humanities,1 distinguishing it significantly from other large-scale funding lines in Germany and elsewhere. Against this backdrop, the format put special emphasis on the international character of the Kollegs to be established because, by and large, the humanities in Germany were (and to an extent remain) less internationalized than the natural sciences, life sciences, or engineering.

Accordingly, the main instrument funded through the KHKs was the invitation of international research fellows to Germany. At our own KHK at Bochum, in a typical year, 10 to 12 fellows would come to visit and stay for 12 months each. This allowed ample time for them to finish important work and publications and, at the same time, created opportunities for us to get acquainted with each other’s work on a deeper level.

The question is, of course, whether these 12 years of exchanges with international fellows have actually achieved ‘internationalization’ at home. Without getting into a discussion on the term internationalization and its possible definitions, it is safe to say that the situation at Bochum is significantly more internationalized now than it was before the start of the KHK. This is apparent, first, because today, more than 30 percent of the scholars working at the Center for Religious Studies, which hosted the KHK, have received their PhDs outside of Germany. Before the KHK started its work, none of our colleagues held international degrees. Moreover, the majority of publications by CERES scholars are now written in English. Even beyond scholarly work, English has become the lingua franca at CERES as a whole, with administrative staff switching between German and English from one conversation to another as a matter of course. Most significantly, CERES is proud to have established a Master’s program in English in 2018, allowing us to include students from around the globe into our teaching unit and securing broad dissemination of the KHK’s research results.

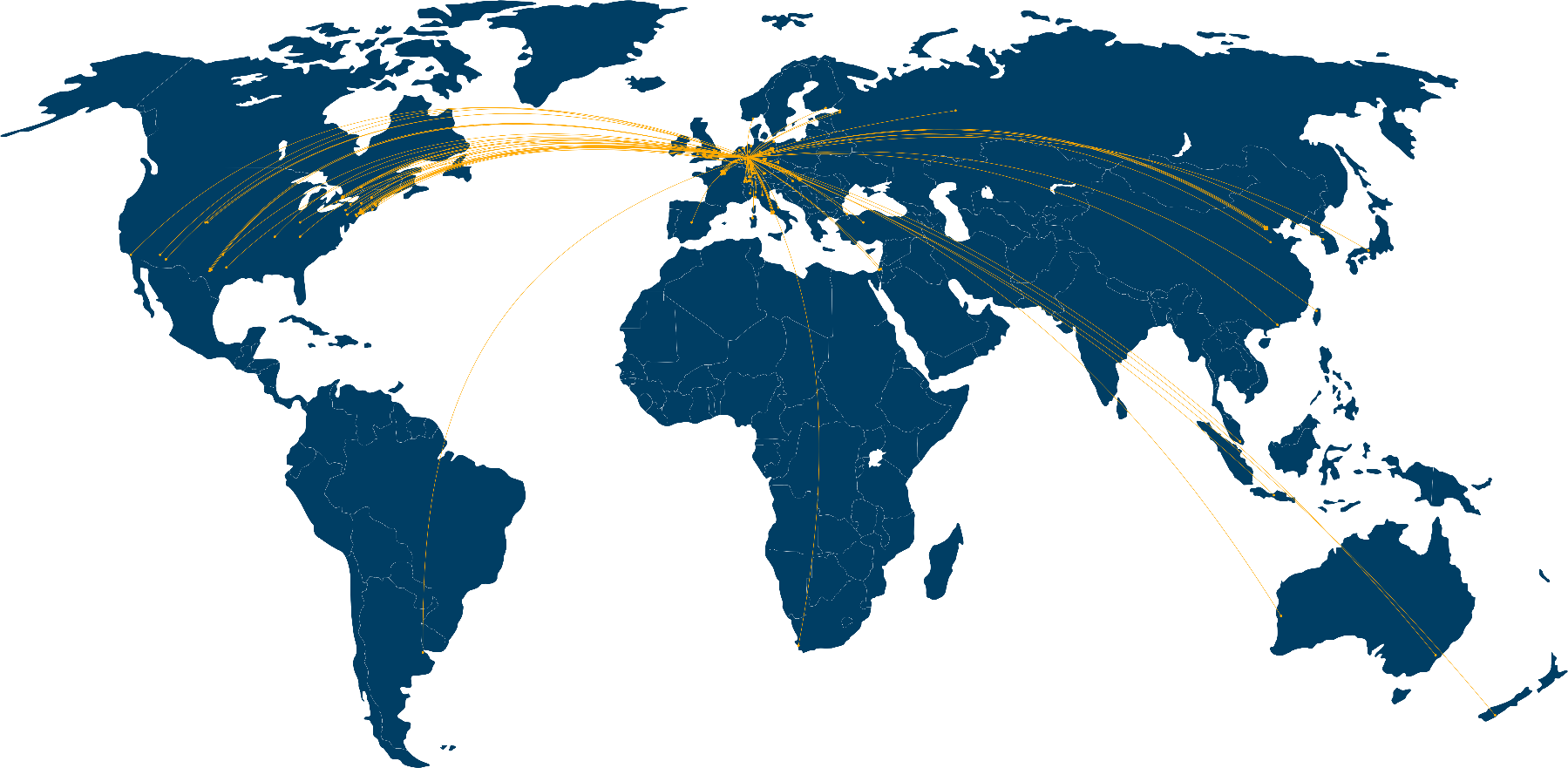

Despite this success, it should be mentioned that most fellows came to Bochum from a ‘Western’ university. Of the 150+ fellows who joined the Kolleg between 2008 and 2020, 36 came from Germany, 54 from within the European Union or Switzerland, and 31 from the United States. This leaves only 29 fellows visiting the Kolleg from all of Asia, Africa, and South America. Clearly, the responsibility for this lies with our KHK’s management and, more importantly, is our loss. At the same time, it obviously mirrors the state of internationalization of the German humanities today, with cooperation and partnerships rarely reaching beyond the scope of the EU or NATO member states (at the risk of overstating it: … of the 1980s). We hope that the cooperation with non-Western academic partners that we were able to establish over the course of the KHK’s lifespan will prove fruitful and allow us to expand our horizons more broadly in the future. These partners include, most notably, the Research Institute for Historical and Philological Studies of China’s Western Regions at Renmin University, China, and the Faculty of Letters and Humanities at Shiraz University, Iran.

While the problem of disproportionate inclusion of non-Western scholars in Western academic contexts is well-known and often discussed, we feel that there should be a more open conversation about a different issue: English as the primary language of scholarly exchange. Obviously, an international research consortium can only work if members speak a common language. But if, at times, no single person in the room is an English native-speaker, the conversation can lack depth and precision. Thus, with internationalization, we have many more scholars contributing to a discussion and therefore a rise in quantity, but the discussion, quite naturally, sustains a loss in quality. To push research forward, this loss needs to be compensated somehow, but how this might be done is not entirely clear yet. One obvious option would be to foster and practice scholarly exchanges in English as early in an academic career as possible. Another, more pragmatic thought is that meetings with international scholars (including conferences) should, whenever possible, be based on written documents disseminated beforehand. In this way, we presume, contributions to a discussion can be more easily traced back to established vocabulary and modes of argumentation, and the state of the debate remain comprehensible for all participants.

“Free Space” vs. “Learning Community”

If internationalization was the first goal the Käte Hamburger line wished to achieve, the second goal is best expressed in the KHK’s slogan Freiraum für die Geisteswissenschaften, which can be translated as “Free space for the humanities.” The idea here is that scholars are often preoccupied with teaching obligations and administrative work and have little time to push their research further. The Kolleg was thus supposed to become a place for researchers to actually do research, which in turn explains why the KHK funding line emphasized fellows staying for extended periods, typically for 12 months.

The idea of “free space,” of course, creates opportunities as well as challenges. On the one hand, the fellows needed time to think, read, and write by themselves. On the other hand, the whole idea of a Kolleg as a community of scholars only makes sense if the fellows meet regularly, present their work, and exchange ideas. Clearly, these two aspects, “free space” and “learning community,” need to maintain a proper balance, but precisely what constitutes such may differ from fellow to fellow. Some came to Bochum with the explicit goal to finalize a particular publication (often a long-unfinished book) and, at times, those fellows decided to skip the majority of meetings and other communal events (the term ‘phantom fellows’ was readily established and, frankly, reflects our disappointment with these colleagues). Quite to the contrary, other fellows very profoundly engaged not only in our weekly Monday meetings but also in the often more than four conferences we held per term, various reading groups, etc.—to the point that some fellows were downright disappointed that most of the activities did not continue during the semester break.

Even with the most engaged fellows, the KHK format was not meant as a framework to jointly work on a research program in the sense of fixed milestones, deadlines, and work packages. For the core researchers of the KHK, i.e., the speaker(s), RUB colleagues, and postdocs, this could sometimes be frustrating. Our thinking did, of course, progress over the years, and through our publications fellows were able to put themselves up to speed before they came to Bochum. In addition, KHK core researchers, particularly the postdocs, would come together after each KHK meeting, take notes of the core results and essential questions, and record them in working papers disseminated in the group.

So we did not have to start all over again with each fellow generation. But of course we could not and did not expect fellows to have internalized our thinking the way we did, including major concepts of a research program. More importantly, new fellows luckily meant new challenges to our thinking. This improved our work significantly and made our thinking more comprehensive but did contribute to relatively slow progress altogether.

A related challenge was multidisciplinarity. Not only could we not expect fellows to be 100 percent familiar with the past work of the KHK, but we also had to deal with dozens of disciplinary backgrounds. This created the need, again and again, to agree on terms and concepts as a prerequisite for a genuine scholarly conversation. As much as this was fruitful and thought-provoking, it was also, at times, tedious. Our most fundamental way to deal with the multidisciplinary nature of our KHK was to try and steer the discussion from the specifics to the generics, from empiricism to theory—and back. So, rather than engage in the specificities of a particular case study, our core researchers kept asking: “What is this study a case of?” Very often, this led to the most fruitful conversations for fellows and core researchers alike.

Administration

Moving to a different country for an extended period of time comes with a lot of administrative issues. Fellows needed to find a place to live, open a bank account, find a spot in kindergartens or schools for their children, etc. Of course, they were never alone in this but had the support of the KHK administration in Bochum. This support did not stop once the fellow had arrived safely in Bochum and settled in. We continued with help in everyday struggles: Who is going to repair my washing machine? Where do I find a good eye specialist who speaks English? How am I supposed to recycle my trash? Etc. Over time, we created a comprehensive Fellow Guide that included basic information for fellows, addresses, and FAQs. This proved very helpful (to those fellows who actually read it).

A common problem for fellows was to follow the complex regulations related to conference traveling, e.g., the maximum costs for a hotel in a particular city, the need to book flights very early to get the best prices, and the issues that would arise whenever a fellow wished to combine a conference trip with either a separate work-related journey or a private vacation. Given that the KHK as a whole and the fellows’ travels were paid for with taxpayers’ money, there is no doubt that strict regulation is paramount. However, if the idea of the funding line was to get the best researchers of the world to Germany, some flexibility should have been incorporated into the regulations. For example, if a fellow finds himself at a small airport in a country where he does not speak the language and needs to get to the conference site, you would want them to be able to take a taxi on KHK money, rather than ask them to please take the bus.

Another common problem for administration in a research consortium relates to meals and catering. Per the university’s own rules, which the KHK statutes required us to follow, meals would only be sponsored if a majority of participants were “external.” Precisely what this meant concerning the fellows as external visitors, on the one hand, but as long-term members of our scholarly community and Bochum residents, on the other, was not always clear. Moreover, to save money, the KHK administration quite often resorted to buying food at a local supermarket and preparing the catering by themselves rather than ordering from a professional caterer. This, in turn, revealed the absurdities of administration rules quite vividly: When it came time to present our expenses to the funding agency, all existing invoices from professional caterers were quickly reimbursed. Supermarket receipts, however, were only reimbursed as they related to food. Non-food items that are necessary if you run the kitchen yourself—such as dishwasher tabs or coffee filter bags—were considered basic equipment (Grundausstattung) of the university and thus not reimbursed. KHK personnel thus had to go through a pile of old supermarket receipts and take out the unwanted items. This tedious work was difficult to justify in light of, again, the taxpayer paying for it.

Sustainability

As large research consortia go, a twelve-year funding period plus another two years for transfer and dissemination is rather generous. In 14 years, a lot can and has been achieved. However, few people would suggest that 14 years are enough to comprehensively understand the complete history of religions between Asia and Europe from the dawn of time to the present day. The question thus is how the work of the KHK will be kept alive after 2022.

The question can be answered on multiple levels. First, on the level of personnel, we are glad that we have been able to keep several former fellows in Bochum, including three former fellows that now hold professorships here. Other former fellows are involved in several KHK follow-up projects, demonstrating sustainability success on a second level. The focus on situations of religious contact, which the KHK has successfully established, has inspired scholars to develop research questions further and apply for other sources of funding. Most notably, two Consolidator Grants, funded by the European Research Council (ERC) and headed by former KHK fellows Carmen Meinert and Alexandra Cuffel, are now hosted at CERES.

Thirdly, these and other projects continue to disseminate KHK-inspired research results in the form of publications, conference panels, etc. Most notably, our book series Dynamics in the History of Religions (Brill Publishers) continues to thrive, as does our open-access online journal Entangled Religions. Many articles are written by former fellows. In addition, most recently, some former fellows agreed to become partners in a research initiative put forward by CERES that will focus on the relationship between religion and metaphor. In each case, the partnership forms part of more extensive cooperation between CERES and the home university department of the respective former fellow. This cooperation includes not only the research level but also a student exchange program.

Most importantly, the work of the KHK continues in the form of CERES. It was founded alongside the KHK in 2008 as a Research Department of RUB. In the beginning, the KHK was more or less identical with CERES as it was the only third party-funded research project hosted here. Over time, however, many more research projects, often inspired by the KHK, were developed at CERES and successfully hosted here. At the time of writing, no less than 20 third party-funded projects form part of CERES. This has been made possible through the researchers’ great enthusiasm, hard work, and creativity in writing all those successful applications. But it could not have been done without the support of the CERES administration team, including professional science management and application counseling, which was financed by RUB and continues to form a core element of CERES.

Thus, the only thing that is missing at CERES when compared with the KHK is the fellows. Universities can be expected to fund management positions and, with the right incentives, create new professorships. But they can hardly be expected to take over the costs for external visitors beyond their jurisdiction. It is thus our position that, in addition to keeping up the funding line as a whole and allowing new KHKs to be created, the funding agency should have given the ‘old’ KHKs, provided they kept some kind of structural basis at their home universities, the chance to continue to invite at least a small number of fellows each year. This would have allowed them to disseminate the KHK results further and push our research forward by integrating new ideas and perspectives.

Final Remarks

Concerning the criterion of internationalization, the Bochum KHK is a great success. Not only have lasting international working relationships been established through it, but the internationalization of CERES staff has also increased significantly as a result of the KHK. One of the future tasks is to intensify relations with the Global South.

In terms of working structures, the format specified by the Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) emphasized individual freedom, which is much needed in a scholarly world often dominated by administrative work. However, the fact that a fellowship was generally limited to a maximum of 12 months and that re-invitations were only possible in exceptional cases meant that continuity of personnel in the individual work formats could not be guaranteed. As a result, the intended “learning community” could only be partially realized. To be sure, some of the central concepts and approaches of the KHK have been ‘taken out into the world’ by fellows. But the KHK is not a suitable format for truly integral collaborative research in the strict sense.

The topic of collaborative research in the humanities has been discussed at universities and in science policy for quite some time. While some believe that collaborative research—especially when compared to the standards of the natural sciences—is not possible in the humanities, others take the opposite view. CERES takes the latter position. In fact, the scholars working at CERES are of the opinion that collaborative research that is integral in the narrower sense is both necessary and overdue in the humanities. This applies not only, but especially to the study of religion. Given the indispensable division of labor, how, for example, should comparisons between empirical material from different times and regions be possible other than through collaborative research? And how should empiricism and theory of the history of religion be related to each other, if not through the cooperation of specialists for the particular and specialists for the general?

The humanities face unique challenges due to their internal differentiation. Regarding special empirical material, linguistic and cultural expertise is indispensable. It is above all the “small subjects” (Kleine Fächer) that have to fear for their continued existence.2 To a certain extent, the small subjects also include area studies. In its recommendations on area studies from 2006, the German Science Council (Wissenschaftsrat) suggests “collecting and coordinating concentration or downsizing plans of individual sites across the Länder [i.e. the German federated states].”3 However, it is not yet clear how this is politically and legally possible against the background of Germany’s federal structure and the cultural sovereignty of each state. In our experience at the KHK, there are essentially two ways to structure collaborative research in the humanities. Either collaborative research focuses on a particular region to explore many of its aspects; for example, the political, economic, and general cultural dimensions of China in past and present times. One of the advantages of this structuring is that one can focus on a region that is often only accessible through specific language skills. A disadvantage is that regional concepts are oriented toward the political dimension—and not infrequently toward modern nation-states. However, the political dimension is often—if not always—not congruent with, e.g., the economic and general cultural dimension. A second way to structure collaborative research in the humanities is to focus on topics such as political, legal, economic, educational, artistic, and religious developments and to examine them in both their historical and contemporary aspects. The advantages of this lie above all in opening up comparative perspectives and being able to look at processes of cultural transfer as well as, not least, global conditions. In this way, topics such as those mentioned can serve as a tertium comparationis, linking more regionally and culturally oriented subjects with more topically and methodologically oriented disciplines. Last but not least, the humanities can come into conversation with the Social Sciences in this way. While the more regionally and culturally sensitive subjects often lack methodological tools and topical coherence, the more topically—partly social scientifically—oriented disciplines such as sociology, law, political science, economics, linguistics, education, and art history often lack the cultural diversification of their subject matter. These disciplines still predominantly focus on the Global North in their research. Moreover, they are usually characterized by a lack of historical awareness and a focus on contemporary developments. One of the disadvantages is that collaborative research structured in this way involves a particularly high level of coordination between the disciplines involved because their sometimes very heterogeneous linguistic and cultural competencies have to be brought in line.

As a Center for Religious Studies, CERES is of course thematically oriented to the topic of religion and religion’s relation to other societal spheres. The same is true for the work of the KHK. In our experience, the advantages of the thematic orientation outweigh the disadvantages of the two structuring possibilities of collaborative research in the humanities. Not only is it possible in this way to relate the contemporary dimension of a topic—in our case religion—to its historical developments. We need specialized knowledge and a division of labor to compare heterogeneous empirical material from different times and regions concerning equality/inequality. We are convinced that the successful future of collaborative research in the humanities lies in a thematic orientation. This also applies to fields such as law, politics, art, education, health, and art.

Regarding the formats of collaborative research, we at CERES have decided to apply to the DFG for a Collaborative Research Center (Sonderforschungsbereich or SFB) after the end of the KHK. This format also has both advantages and disadvantages. Among the advantages, in addition to the promotion of young scientists, is a clearly defined and operationalized research program to which all subprojects are oriented. In this respect, an SFB enables particularly integral collaborative research. One of the disadvantages of the SFB format is that it fulfills the criterion of internationalization only to a limited extent. Although it is possible to apply for a Mercator Fellows module, this tool is quantitatively, and in comparison to the KHK format, not sufficient to achieve sustainable internationalization. With the Centers for Advanced Studies in humanities and social sciences (Kolleg-Forschungsgruppen), the DFG has established a format that is based on a fellow structure. Thus, it has the same advantages and disadvantages as the KHK format. Perhaps the best of all research collaboration worlds for the humanities would be to make the SFB format international from the outset, as is the case with the ERC formats. For example, the DFG does have the SFB/Transregio program option, but only one of the participating institutions can be abroad. The ERC formats are more flexible in this respect.

Concerning the administrative handling of internationally oriented collaborative research projects, there are still major challenges, not only in terms of internal administration but also with regard to the coordination between the internal needs of corresponding projects, the requirements of the university administration, and the conditions of the funders.

However, despite the described disadvantages of the KHK format and the great effort in setting up the KHK in Bochum, none of the CERES-based participants would ever want to do without this experience. It has been a great scientific adventure and the learning success helps us to further advance religion-related collaborative research.

Based on the experiences with the KHK, the structure of CERES is understood as a contribution “to establish institutions that promote empirical and theoretical knowledge in a comparative perspective.”4 In this respect, CERES complies with the recommendation of the German Science Council “that institutes for scientific studies of religions, i.e. permanently established larger teaching and research units with at least four professorships, be set up at several locations in Germany.”5

In an update to the funding line, it was announced that from 2021, KHKs can also be set up as collaborative projects bringing scholars from the humanities together with colleagues in life sciences, natural sciences, and engineering. See https://www.bmbf.de/bmbf/shareddocs/bekanntmachungen/de/2019/04/2386_bekanntmachung (last accessed March 3, 2022).↩︎

With regard to the “small subjects,” the BMBF funds the “Small Subjects Unit” (“Arbeitsstelle Kleine Fächer”), a research and service institution based at the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz; see https://www.kleinefaecher.de/ (last accessed March 3, 2022).↩︎

Wissenschaftsrat, Empfehlungen zu den Regionalstudien (area studies) in den Hochschulen und außeruniversitären Forschungseinrichtungen, Mainz 2006, 48. Translated by the authors.↩︎

Wissenschaftsrat, Empfehlungen zur Weiterentwicklung von Theologien und religionsbezogenen Wissenschaften an deutschen Hochschulen, Berlin 2010, 87.↩︎

Wissenschaftsrat, Empfehlungen zur Weiterentwicklung von Theologien und religionsbezogenen Wissenschaften an deutschen Hochschulen, Berlin 2010, 87.↩︎